Roy Keane at 50: Cork to the core, Rebel legend always did it his way

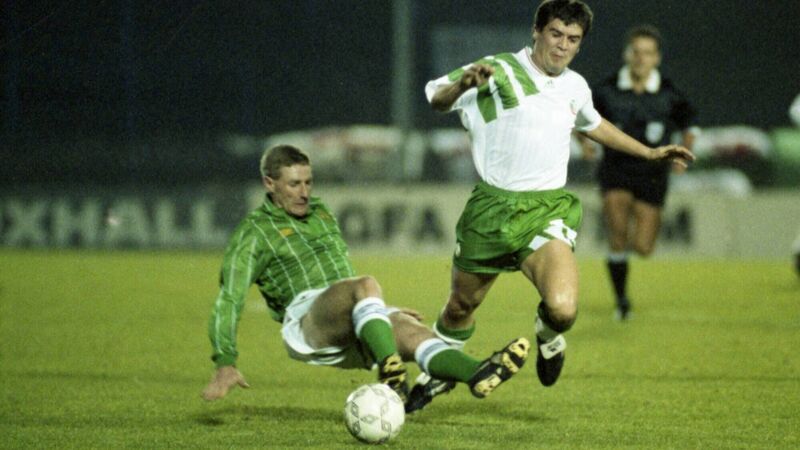

Roy Keane is brought down by Nigel Worthington during the World Cup qualifier at Windsor Park in November 1993. Picture: Eddie O’Hare

"Cork is no place for sensitive folk. To succeed there, you have to have the skin of a rhinoceros, the dissimulation of a crocodile, the quality of a hare, the speed of a hawk. Otherwise, the word for every Corkman is to get out and get out quick.”

Sean Ó Faolain

ON Saturday afternoon, May 29, 1993, Roy Keane played for the Republic of Ireland in David O’Leary’s testimonial match against Hungary at Lansdowne Road. The kind of fixture he wouldn’t be seen dead in later in his career, he was young then, and things were different.

From the Hungarian kick-off, Niall Quinn intercepted a pass and played it directly into Keane’s path. He ran straight at the still-cold visitors’ defence and then let fly from 25 yards. The goalkeeper didn’t even move. The whole operation took less than five seconds and he celebrated like somebody who’d just scored the goal to send his country to the World Cup finals.

If the rest of that game didn’t go quite as planned, Jack Charlton’s side lost 4-2, Keane had still done his part. He’d turned up. The most coveted player in the English game had put aside the constant speculation about him moving on from Nottingham Forest and arrived to contribute to the celebration of a departing Irish great.

That night though, Keane eschewed the formal dinner and team activities to fly to Cork. As always at that point in his life, his first thought was to return to his hometown, to his mates, to his brothers. To the bosom of the place that raised him.

Many would have found this laudable. After a season in which he’d become the hottest property in the British game, he wanted to be with his own people the first chance he got. What’s not to like about that? A star rises inexorably yet wants to keep putting his feet back on familiar ground.

When the 21-year-old walked up to the door of Cubins nightclub on Hanover Street that evening, the arm of the lurching bouncer immediately came across to block his path. The head shook from side to side. Words were exchanged.

Anybody who has ever been turned away from their preferred destination of an evening could recognise the ritual playing out. Keane wasn’t welcome at the inn.

I watched this happen from about 10 yards away. I knew Keane from playing against him in schoolboys’ soccer in Cork when he was part of the all-conquering Rockmount team of all the talents. Moments before, I’d spotted him walking on the street where crowds milled around after closing time on Washington Street, one of the city’s main drags, considering their nightlife options.

Myself and my friends nudged each other at the sight of the city’s newest celebrity back in our midst, just hours after headlining at Lansdowne Road. We watched him head up to the door of Cubins and stared, the way people do when they see somebody famous (even as freshly-minted a celebrity as this) up close. Never mind that we’d often seen him up closer on the football field. That was before. So much had changed.

Over the ensuing years, everybody in Cork would come to have their own Keane story about an incident inside or outside a nightclub or a pub. Some of them would even be true.

In many of these tales, he’d be decried for acting the big shot, throwing money and the weight of his celebrity around. On this particular night on Hanover Street though, this early in his ascent, there was no gauche attempt to flaunt his new position. He just stood there for a moment, maybe hoping for a change of mind from the man in black with the earpiece, and then he walked away. Like a hundred others, he’d been refused entry on the mysterious whim of the doorman and he accepted the ruling.

Except in the case of this particular punter, there was something very different afoot, something which tells us a lot about the nature of Irish begrudgery. In Manchester or Liverpool or London, an English international footballer approaching the door of a nightclub hours after representing his country would be embraced with open arms.

More than that, they’d be ushered inside in a welter of handshaking and backslapping and generally given the VIP treatment by management grateful to have stars, genuine stars, on the premises. Indeed, a bouncer who failed to recognise a famous footballer coming in, not to mention delightedly turning one away, might end up getting the sack.

Keane was just 21 years old that night. Over the previous three years, he’d transformed himself from a young apprentice with no more than a one in ten shot at making it as a professional footballer into the transfer target who would dominate the headlines that summer. With his performances for Forest and for Ireland, he’d also put Cork on the map.

Cork people never tire of hearing their hometown being talked about and there was no shortage of mentions, even during Nottingham Forest’s disastrous Premier League campaign which culminated in relegation, the result which spawned so much talk that their best player would have to move on to bigger and better things immediately.

“Most people were fine, their attitude being ‘fair play to you boy’,” wrote Keane in his autobiography about the initial reaction of Corkonians to his success. “Others seemed to take a different view. I might be queuing for fish and chips or a kebab (my favourite) when I’d hear someone asking ‘Who does he think is?’ A small thing but incidents like that reminded me that fame came with something of a price tag.”

The adverse reaction of so many compatriots and fellow citizens to Keane even at this early age can be given many labels. Australians call the tendency to disparage high achievers “tall poppy syndrome” as those below try to cut those growing too large back down to size. Sociologist Max Weber terms it “zero-sum prestige” as there is not enough praise to go around so people hate to see their peers getting more than themselves.

In Ireland, of course, we have our own peculiar word for it. Begrudgery.

The Collins English Dictionary classifies begrudgery as a “noun – informal (Irish) resentment of any person who has achieved success or wealth.” We can’t take umbrage at that definition or at others who describe begrudgery as “the Irish disease”. How could we be offended? After all, we often joke begrudgery is truly our national sport, more fun than Gaelic football, more widespread than hurling and more uniquely ours than soccer.

Did the bouncer refuse Keane entry because he didn’t recognise him? Hardly. He was by then well on his way to becoming the most famous soccer player the nation had ever produced. Was the rejection because Keane had previously misbehaved in Cubins on a night out?

Possibly, though no record exists of him doing any such thing. Can we surmise then it was just a bouncer flexing his metaphorical muscle, showing the city’s newest millionaire (back at a time when millionaires were invariably grey-haired and old-moneyed) who was boss?

Of course we can. To the outsider looking on, this was a classic case of begrudgery, laced with envy, and sprinkled with resentment.

Hours earlier Keane had the Lansdowne crowd on its feet just seconds after many of them had taken their seats. Now, he was being put in his place on the streets of Cork. I tend to think this way about the incident because I witnessed so much of what came after over the next decade. I heard so many put-downs, so many malicious rumours, so many attempts to cut the tall poppy back down to size.

For all those willing Keane on to greater things and taking pride in his achievements as a Corkman, there were plenty unable and unwilling to applaud his journey towards greatness. Long before Saipan, they grudged him every step he made towards the top.

Just over three years later, on the afternoon of Sunday, November 10, 1996, Ireland took on Iceland in a World Cup qualifying game at Lansdowne Road. A routine fixture on the calendar it would go down in history, not just for being a terribly dull scoreless draw but for something else entirely. This was the first time in living memory that an Irish international was booed by his own supporters on his home ground.

Not lustily booed. It was more sporadic than sustained. But there was genuine booing several times that the Corkman touched the ball. It was unmistakable and, you could argue, it was orchestrated.

In a column in newspaper that morning, sports journalist Cathal Dervan had called on fans to boo Keane, to let him know what they thought of his (perceived) cavalier approach to playing for Ireland. The previous May, Keane had rather ham-fistedly pulled out of the Irish squad heading to the US Cup, a meaningless end-of-season tournament that involved games in New York and Boston. He claimed to have informed newly-installed Irish manager Mick McCarthy of his intention not to go well in advance, McCarthy claimed to know nothing of this until Keane didn’t turn up for training.

A precursor of much more controversial battles to come between the pair down the road, the incident became tabloid fodder for a few days, dominating the headlines. At one stage, it was asserted that Keane was “missing”. He wasn’t. He was at a cricket match with some other United players, a typical end-of-season jolly for professional footballers, especially a squad celebrating achieving its second league and cup double in three years.

In any case, the whole brouhaha eventually died down. McCarthy took a young squad to America in June and blooded half a dozen decent prospects. Keane missed out on what he regarded as a pointless trip and, due to suspension and injury, it was November before he was ready to return to action for Ireland. Six months might have passed but for many the sore from back in May had been festering.

Dervan was one who felt particularly aggrieved and, as he was entitled to do, he chose to unload on Keane in print. Was this begrudgery or a journalist asserting his right to an opinion, however controversial?

Maybe both. Keane and Dervan had history. Very interesting history. Very Irish history. They had once been good pals. When Keane moved to United, still very much in the hard partying phase of his life, Dervan had been the soccer correspondent of the in England, a role in which he’d grown very close to many Irish players. They had socialised together with predictable results.

“I'll even tell you what it's like to pick Roy Keane out of his own puke in a Manchester Airport hotel bar, as I did some years back only days before his first European Cup appearance for United,” wrote Dervan. “Now, to be honest, I regret I didn't leave him to drown in his own vomit, though he is making rather a good stab at that himself as we speak.”

By then Keane’s biggest nemesis in print, Dervan made the call for the fans to boo but the startling fact is, even with rather small readership, there were so many in Lansdowne that day willing to carry out his instruction. Why? Did they feel that passionately about the long-forgotten US Cup? Were they offended by him turning down the opportunity to play for the country, no matter what the circumstances? An eerie foreboding of future issues there too.

Or were they just ignorant fools wanting to do down somebody already on his way to becoming the most decorated Irish player ever? Were they the Irish supporter equivalent of the bouncer outside the Cork nightclub begrudging the rich, famous footballer by now established as the fulcrum of the Manchester United midfield?

If it could easily be argued, the answer is all of the above, it’s also worth pointing out that the Irish fan demographic was undergoing something of a transformation at this time. Throughout the '90s, soccer had grown in popularity around the country, largely on the back of Sky Sports’ relentless hyping of the Premier League. This brought people to the game who’d never been to internationals before. It also brought many whose first allegiance was to English clubs they watched religiously each week, never visited yet bizarrely liked to think of as their own.

More of that later. For now, it’s worth pointing out something else. These supporters were capable of bizarre behaviour towards players, whether prompted by journalists or not. This much was demonstrated in an unfortunate incident that took place in May, 1998.

At half-time during a senior friendly against Mexico, the FAI made a presentation to the Irish Under-16 squad which, under the tutelage of Brian Kerr, had recently won the European Championships. As the first Irish team to ever win a major trophy at any level, a seismic achievement, the teenagers got a huge reception as they walked on to the field. Well, they got a huge reception collectively. When it came to the individual introductions, things went a little awry.

Kevin Grogan, Graham Barrett and David McMahon all received hearty boos from the crowd when their names were called. Why? Because the PA announcer also mentioned the clubs they played for in England; Manchester United, Arsenal and Newcastle United respectively. Think about that.

Three U16 footballers walked out in front of an Irish crowd at Lansdowne Road having just played their part in a huge international success and were jeered because they were young apprentices at certain English clubs.

Keane wasn’t in Dublin that afternoon but he would have recognised that supporters willing to denigrate young boys (only one of whom would go on to play senior for Ireland) as they enjoyed their finest moment in the sun were capable of begrudging anybody anything.

In the spring of 1997, a television crew was assembling equipment outside the Templeacre Tavern on the northside of Cork city. A couple of miles from Roy Keane's birthplace in Mayfield, the public house was the appointed venue for an interview with the player as part of a documentary being made about his life. As the cameraman took some footage of the pub's frontage, he was stopped by a passerby.

"What are you doing there?" he asked.

"We're making a TV programme about Roy Keane," replied the cameraman.

"What are you making a programme about that **** for?" came the next question.

At the time, Keane was on the verge of his third Premiership title in four years, he had figured prominently in the PFA Player of the Year voting and Alex Ferguson had just made the first public noises about him becoming a future Manchester United captain. Still, in his home town, the black hand of begrudgery has never been too far away.

In some parts of Cork, there were as many jeers as cheers greeting United's victory over Juventus in the semi-final of the 1999 Champions’ League. Despite the presence of Keane and his fellow Corkman Denis Irwin in the starting XI, the moment when Urs Meier produced a yellow card to punish Keane for his foul on Zinedine Zidane provoked howls of delight in certain city pubs.

The derision emanated from those fellow citizens of the Manchester United captain and left-full who have spent that entire Champions' League campaign rooting for Italian, German and Spanish footballers against two of their own.

Through his column in the , it was Dinny Allen, a sporting folk hero of another era, who first highlighted this unsavoury tendency whereby not everyone took pride in the success of the local boys. The fact that they plied their trade with United, equally loved and despised as earlier established, seemed to preclude certain sections of the city's population from celebrating their achievements with good grace.

It's a startling commentary on the country’s utter consumption by the English game that perceived loyalties to clubs on another island can divide neighbours and allow envy and resentment to flourish so.

In Cork, a place where sporting success is regarded as a birthright, the 1990s were a fallow decade. After the dual All-Ireland success of 1990, the county's Gaelic footballers and hurlers fell on hard times, the dark years brightened only by the stellar contributions of Keane and Irwin to United's eminence. That they were impacting on the world stage was a source of pride to many in a town where sport matters so much that even in the '50s, a time of mass emigration, Raich Carter was reputed to be the best-paid footballer in these islands when playing for Cork Athletic.

In the same way that, decades later, the local wags would dub Keane's father Maurice "Sterling Moss" on foot of his son's newfound wealth, they affectionately christened their illustrious import "Rich" Carter. Yet, for all the wit that courses through the town, the greatest crime a Corkonian can commit is to appear to forget where they came from after they leave.

That neither Keane nor Irwin could ever be accused of such a grievous slight made their denigration by some all the more remarkable. Few people who make their lives away from the city have kept such strong links with it as this pair.

"People ask me where I'm from when I'm in England and I always say Cork first, then Ireland," said Keane during that 1997 documentary.

That this is how he spoke about his home town in a television interview made it all the more disappointing that some people couldn’t ever properly acknowledge the enormity of what he was doing in his career. Little wonder that over the years, he’d change his tune about his feelings for home.

“I live over here now,” said Keane in 2004, “and people may wonder why I don’t probably intend to go back. Well, it is the way things are over there. They are quite happy to knock people. Being honest, I feel really let down by what has happened in Ireland.”

App?

App?