Dave Hannigan on what made the late Tom Kiernan a Leeside legend

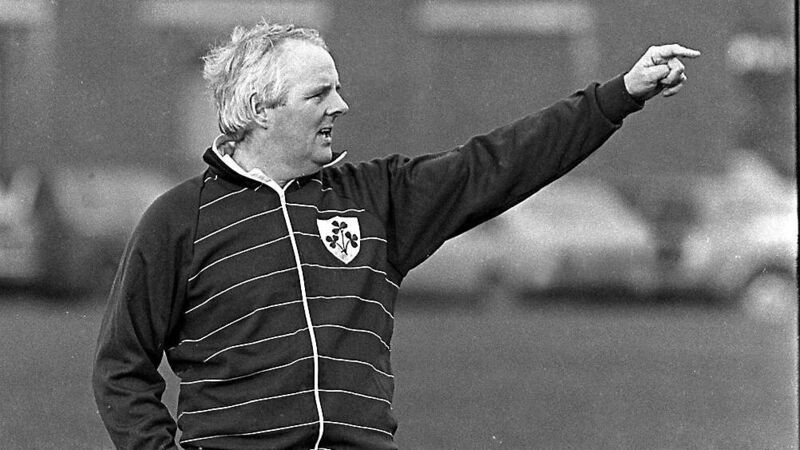

Tom Kiernan in 1983. Picture: SPORTSFILE

He captained UCC, Cork Constitution, Munster, Ireland, and the British Lions, and, for a long time, was the most-capped full-back in the history of the sport.

To that point, the Munster students had never emerged from Belfast victorious and that year’s northern crop was formidable, bulwarked by one Willie John McBride.

“Tom came into the side and it really was his cuteness that won the day for us,” recalled Jim Riordan, another member of that team.

“The Grey Fox belonged in the old last-line-of-defence school of full-backs whose priority was to catch well and find an unerring touch,” wrote Gareth Edwards in his book, 100 Great Rugby Players.

“He played a nerveless humdinger at full-back and the joy of my uncle’s group was unconfined — and, of course, Tom Kiernan went on to be the world’s most-capped full-back, captain of the Lions, and Munster’s coach when they beat the All-Blacks. And I was to grow up and become a friend of his until we stupidly fell out – completely my fault.”

“First Cup medal. First time to play for your country. First Irish team to beat the All-Blacks. It’s only human to have doubts. You don’t know if you can do it or not. Outside of Munster, people made you feel you weren’t good enough. But Kiernan put the belief into us. He convinced us we could do it.”

“Kiernan was an absolute rock,” said Campbell. “People forget that going into the Welsh game we had lost seven and drawn one of our previous eight games. We had been whitewashed the previous season but, as Moss Keane, it had been Ireland’s best ever whitewash!”

App?

App?