Memories of Cork city that are frozen in time

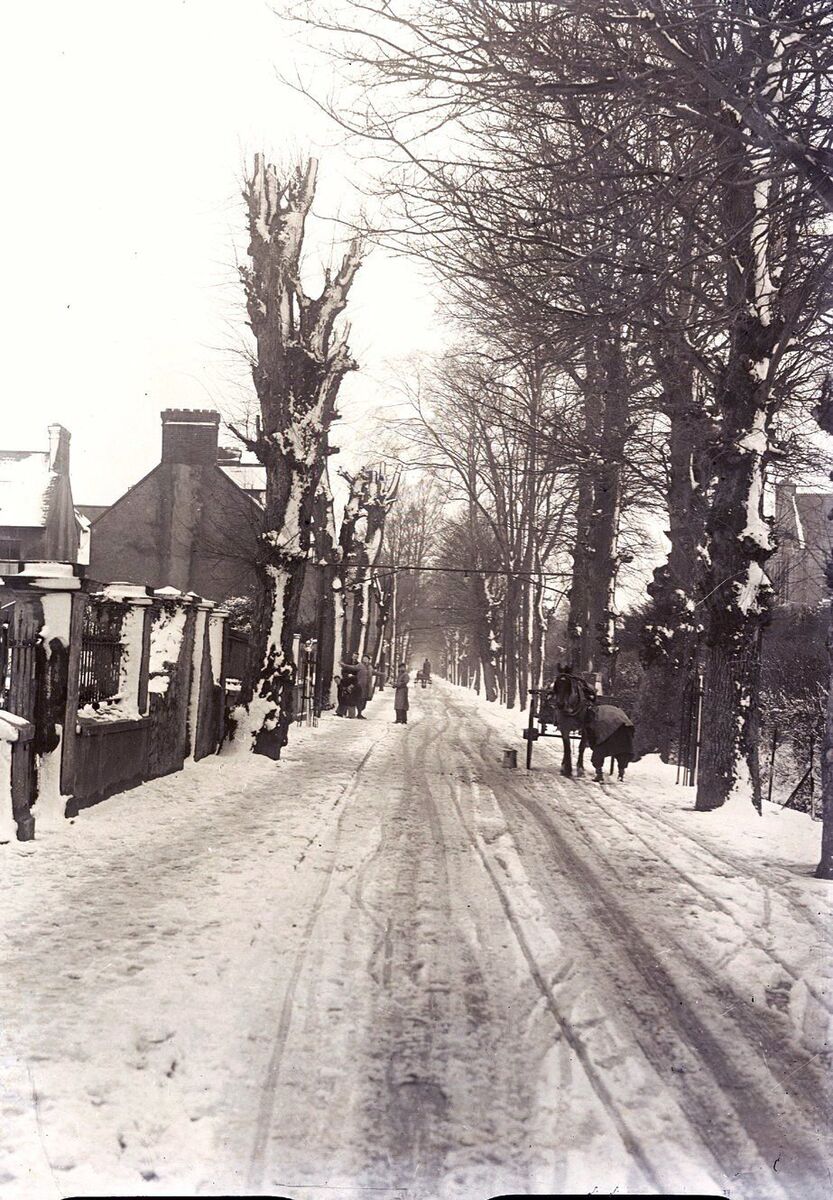

Snow on Academy Street in 1947. In modern times, the winter of 1947 remains the harshest ever in Ireland.

During the reign of King Charles II (1660-1685), Cork experienced plenty of harsh winters, in particular 1683 stood out as one of the worst on record. A severe frost lasted for several weeks and during Christmastime carriages and cattle passed over the frozen River Lee. On the medieval ‘Key’ of the Walled Town (today’s Castle Street) vessels were frozen to the river bed; and under the shadow of their tall masts many citizens from the town and the suburbs partook in the delightful recreation of skating and game playing on the frozen channels. These waterways would have comprised of St Patrick’s Street, Grand Parade, South Mall, Cornmarket Street, Grattan Street, Sheares Street, Henry Street and the Lee’s north and south channels.

During the Georgian period (1714-1830), as the town wall was slowly disappearing from the landscape, the city witnessed more severe frosty winters. For instance, the winter of 1739 was the hardest in living memory. This was called the hard or black frost. Vessels were frozen to quays along the middle xhannel, today’s St Patrick’s St, as well as to the other quays.

Tents were pitched on the frozen Lee, from the north strand (today’s MacCurtain St/St Patrick’s Quay/Lower Road) to Blackrock, and many jolly Corkonians passed the time away skating to and from to the village of Blackrock. The following Christmas saw the heaviest snowfall in 40 years. The snow was six feet deep in areas and travelling came to a standstill. In addition, many houses and structures with thatched roofs collapsed under the heavy weight of the snow. On a lighter note, scores of children had fun sculpturing figures in the snow and snowballing.

In 1788 the citizens of Cork celebrated another icy winter; and a new bridge was erected across the north channel, St Patrick’s Bridge (a toll bridge). Due to the severe low temperatures, the south channel was frozen and the easily pleased locals, many living in ice-cold tenements and dark smoke-filled hovels or cabins from Barrack Street, Globe Lane, French’s Quay, Cove Street and the neighbouring lanes off South Main Street, availed of the opportunity by skating on the channel and playing under the present South Gate Bridge (built 1713).

The distinguished Cork Historian and writer CJF MacCarthy tells us that the frozen Lough helped to put many a hot dinner on a poor family’s table, reminding us of our less well-off brothers and sisters at Christmastime. Throughout the Victorian period (1837-1901), idle men of the city looked forward to the employment given in breaking the ice on the Lough and drawing it to the ice houses, which were sited on Lough Road. The ice money or profits from the sale of the ice was divided up by the Cork Corporation between hospitals and charities.

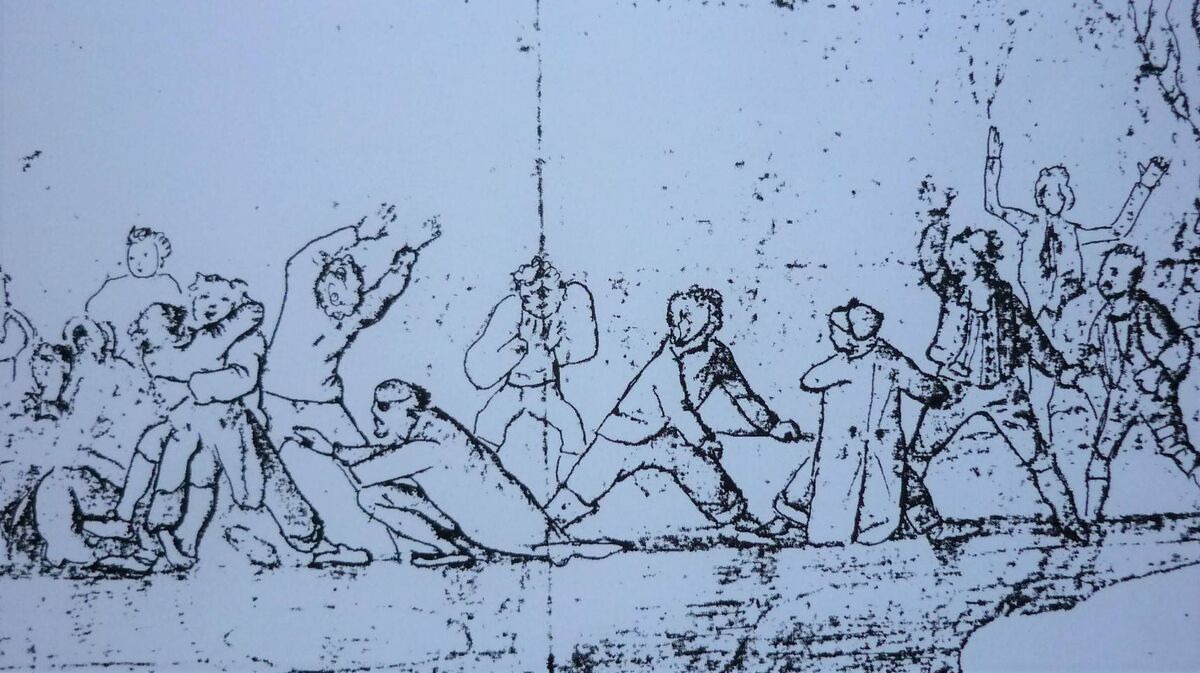

Victorian Cork also witnessed many harsh winters. The Cork artist Daniel Maclise has left us numerous elegant sketches of Christmas past.

One shows a group of young jolly Corkonians having fun skating on the Lough.

This was a popular Christmas pastime back then enjoyed by all ages.

Over the years, I’ve chatted to numerous senior citizens and several have told me stories about their experience growing up in the Marsh in the densely populated Middle Parish and Blackpool area in the 1920s, 30s and 40s.

Cold, damp, rat-infested tenements, and cottages were the norm; in these hovels, one tap and one toilet serviced a family of tenements which would consist of four to five families and more.

During cold icy winters, many of their taps and toilets would be frozen solid along with the water pumps around the Middle Parish and Blackpool. Consequently, many of the residents were forced to make a daily pilgrimage to and from Grenville Place, Bachelor’s Quay and the Coal Quay from the River Lee and the River Bride to fill their buckets full of water — at the time the rivers were open sewers.

This water was used to prepare their meals — boiled first of course, and for washing.

In modern times however, the winter of 1947 remains the harshest ever in Ireland.

From January 19 to March 15 an arctic cold snap led to five major blizzards and caused many deaths.

The Lough was completely frozen over and children and adults skated and played games on it for weeks.

And though I love to see a Christmas card depicting a snow-covered winter wonder land, here’s hoping all cold snaps are behind us as 2022 comes to a close and we look forward to a bright 2023.

Francis H Tuckey, The County and City of Cork Remembrancer; or Annals of the County and City of Cork. 1837 Tom Foley, historian, Blackpool Historical Society Journal of the Cork Historical & Archaeological Society. 1893 CJF MacCarthy files Cork City Library files.

App?

App?