The remarkable life of Sister Ann: A nun like no other

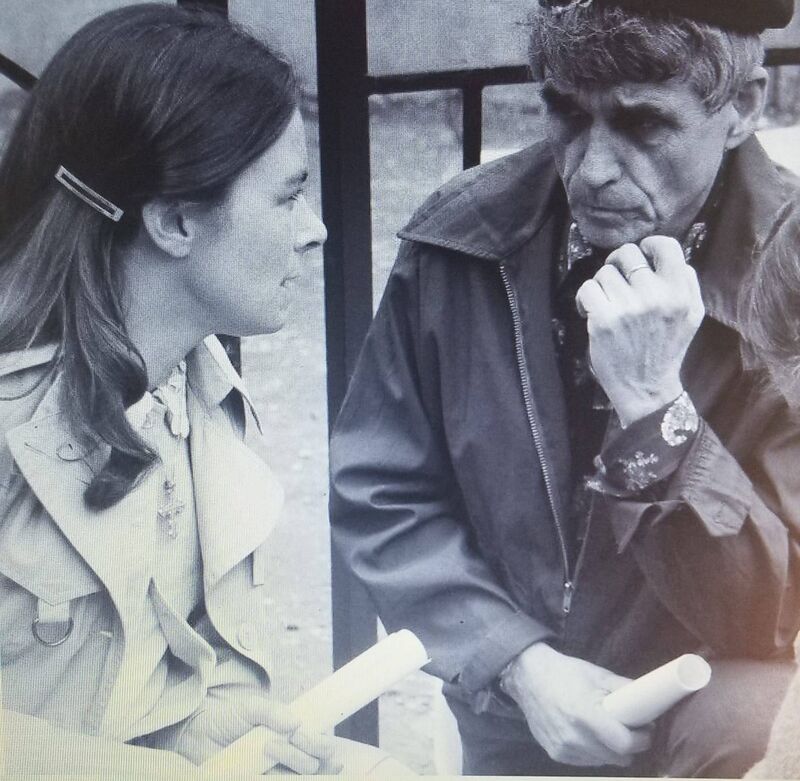

WOMAN OF COURAGE AND CONVICTION: Sister Rosaleen O'Halloran in New York around 1964

MY first memory of my cousin, Ann O’Halloran, is seeing her clad in black leather, riding on the back of her boyfriend’s BSA bike while speeding past Cork City Hall. She was 16.

Hunger strike in solidarity with Sands

ON May 2, 1981, a petite lady approaching her 40th birthday deftly put her shoe through the glass front door of the British Airways offices in Manhattan.

This was all part of a series of protests by Cork nun Ann O’Halloran - Sister Rosaleen - to draw attention in the U.S to the plight of Bobby Sands and his fellow hunger strikers in the Maze Prison in Northern Ireland.

Ann went on an 11-day hunger strike outside the United Nations building in Manhattan in solidarity, and did a similar protest in Washington and an all-night vigil on the steps of St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. TV camera crews followed her protests, which made headlines around the world.

Sands eventually died on May 5, in a protest - which included the deaths of nine other hunger strikers - against the British removal of Special Category Status for IRA prisoners. The deaths attracted both praise and criticism and put the Troubles on the global map.

On May 12, 1981, Ann caried out another public protest, when she rushed onto the stage at a charity dinner function for the Ireland Fund Awards in New York, and pleaded with the audience to recognise the “martyrdoms” of Sands and his fellow hunger strikers.

The spotlight on the stage was shut off, but the nun resisted attempts to remove her and persisted to call for support for the hunger strikers, before being led away sobbing.

Ann was passionate about starting a serious dialogue to bring about peace on her home island, and worked with other religious leaders toward a peaceful and just solution to the conflict.