Beetroot juice for lipstick, bread soda for toothpaste... life in Cork during Emergency

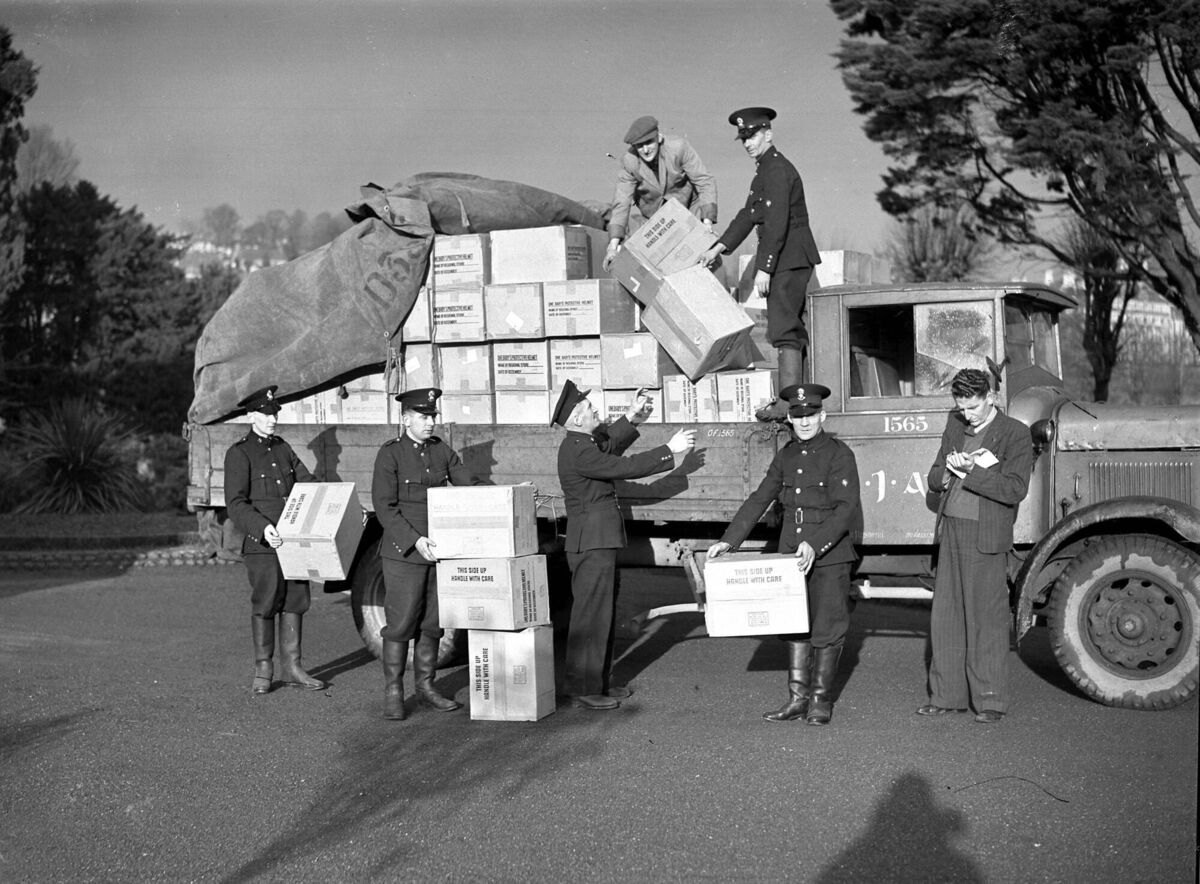

BE PREPARED: A gas mask demonstration at Fitzgerald's Park, Cork, during the emergency years

FUEL and food rationing, disrupted travel, air raid precautions, censorship, compulsory tillage-growing, and the constant fear of invasion.

Just some of the challenges Cork faced during The Emergency from 1939 to 1945. Its people responded with resilience and a self-sufficiency born out of adversity and need.

Mothers cut the toes from shoes when their children outgrew them and called them sandals. If heels were worn - they sent them to the cobbler. They made blouses for their daughters from pillowcases and turned flour bags into tablecloths.

Men sharpened razor blades with edging stones. They substituted bread soda for toothpaste, polished shoes with black soot from the fireplace, and met a craving for cigarettes by rolling dried tea leaves and brown paper.

Women used beetroot juice for lipstick and drew fake seams with eyebrow pencils on the backs of their legs, which they had painted with a coloured liquid to create the impression they were wearing nylon stockings.

Farmers were required to plant more acres with food-producing crops. Families grew their own potatoes and other vegetables. The grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin were ploughed, and local authorities allocated townspeople free allotments to stave off food shortages.

Clothing was passed down from child to child. Nothing was wasted. Patches were sewn on the worn knees of trousers, socks were darned, sewing machines hummed in kitchens. Some mothers even converted horse collars into comfortable cradles for their infants.

A timber tea chest acquired from a friendly shopkeeper was turned into a play pen with a worn rubber bicycle tyre tacked to the rim to protect small children from rough edges.

At least 100,000 people from this island served with the Allied forces - over 3,600 from the south and nearly 4,000 from the north were killed. Thousands more emigrated to Britain out of economic necessity.

The Irish state did not escape some of the horrors. More than 400 people lost their lives here, mainly in Axis and Allied plane crashes, German bombings, and incidents at sea.

When it all started, the nightly black-out was a curiosity. Families brought their children out “to see the darkness” in Cork and other cities. Hurricane lamps with red globes were placed on kerbsides in suburbs as a guide to drivers.

“Are we invaded yet?” became a conversation opener by people stopped at Garda/Army checkpoints, and a satirical song “thanked de Valera and Sean MacEntee for giving us black flour and a half-ounce of tea.”

In a bid to keep essential transport supplied with tyres, Dunlop set up coastal teams to salvage bales of crude rubber swept from ships wrecked at sea.

The Defence Forces were expanded to almost 41,000 members. Garda Sergeants drilled the Local Security Force on country roads and in village halls, shouting commands repeated later by children using hurleys and brush handles as mock weapons. Newly commissioned Army officers who lived in barracks earned eight shillings a day, with ten pence a week deducted for haircuts and laundry.

‘Corner Boys’ kept a look out for strangers in towns, and the tumble of every porpoise along the coast was taken by watchers to be that of a submarine periscope.

Cocks of hay swept down the side of Caherbarnagh Mountain on a windy day in Kerry were mistaken for parachutes. Smoke rising from high ground beyond Castlebar on the day the war broke out led to a security alert. Gardai didn’t find enemy agents hiding in the bushes, but returned to their station with a five-gallon drum of poteen and a still.

Fishermen occasionally came face to face outside Irish territorial waters with German submarine crews seeking to buy fresh fish.

After a report German forces had landed near Dingle, an LDF member was sent out on a bicycle in the middle of the night to summon volunteers to defend a bridge on the Cork-Kerry border. A farmer, roused from his sleep, answered the call to duty, but with a revealing caveat: “Tell the Captain, I’ll be down first thing in the morning - after the creamery.”