Brave Cork people should be celebrated on 80th anniversary of D-Day

A post office worker in Blacksod in Mayo, one of Maureen’s duties was to deliver weather forecasts, and her prediction of a brief interlude in the poor weather in northern France in early June, 1944, was key to the Allied forces’ decision to go ahead with the D-Day landings.

Maureen died shortly before last Christmas aged 100, and her actions 80 years ago are rightly held up as an example of how this country wasn’t quite as neutral during World War II as some now would lead us to believe.

However, is there a risk that, in remembering her story, we are damning this country’s actions during World War II with faint praise?

Because Ireland - and, indeed, Cork - did so much more on D-Day than provide a weather forecast.

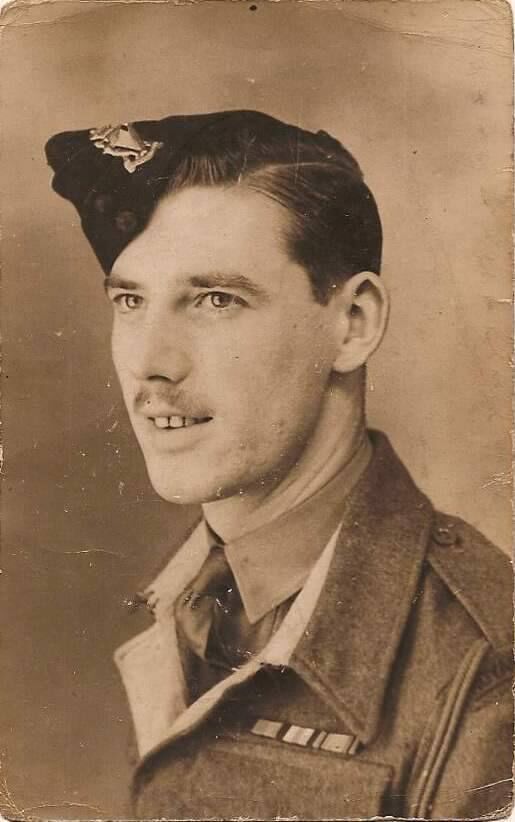

Take the experience of Pat Gillen.

A rifleman in the Royal Marine Commandos, he was among the first wave of troops to land on Sword Beach on June 6, 1944. As he was about to disembark his craft, his officer declared: “If you want to see your grandchildren, get off this landing craft faster than Jesse Owens!”

After surviving the landing, Pat underwent a six-mile trek through marshland to secure the strategically important Pegasus Bridge, near Caen.

Galway-born Pat went on to work for Ford in Cork for 38 years, the latter 11 as its press officer, retiring when it closed in 1984.

Like many a former soldier, Pat seldom talked about the horrors of war and his exploits only came to light a fortnight before he died in 2015, aged 89, when he received the highest French honour, the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, from the French ambassador to Ireland, in recognition of his role in its country’s liberation.

With characteristic generosity, he dedicated the medal to fellow countrymen, including two cousins who died in the war, saying: “By the grace of God, I survived to be here today while many of my friends sleep in the fields of France.”

An estimated 120,000 Irish fought with Britain in the war, among them 4,983 who ‘deserted’ the Irish Defence Forces to do so - they were finally pardoned in the Dáil in 2012. Sadly, there were only around 100 left alive by then to hear it.

In the month of D-day alone, at least 301 Irishmen were killed with British and Canadian forces - a further 550 would die before the war ended over a year later.

Many of the Irish of that generation who survived World War II were humble by nature, and some nationalists here had little time for men who had served in the British forces - even when it was taking on the most despised and lethal fascist force the world has ever known.

John Shanahan, a Corkman with the 2nd Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles, recalled of June 6, 1944: “We hit Sword Beach just after 9.00 hrs. Actually, we landed in about 4ft of water. I remember my big concern was not to get my rifle wet.

“The landing area was heavily defended and we met mortar and heavy gun fire. Of course, there were some soldiers who did not manage to get as far as the beach...”

This witness account is typical of its time - dry, stoic, matter-of-fact, understated - and appears in the 2019 book A Bloody Dawn: The Irish At D-Day (Merrion Press), by Corkman Dan Harvey, a retired Lieutenant Colonel with the Irish Army.

“The story of D-Day is enormous, and the Irish have a rightful place among its many chapters,” wrote Dan. “Veterans rarely spoke about it, and many served under assumed names in non-Irish regiments.”

On D-Day, Jack Allshire, from Crosshaven, was also in the Ulster Rifles, in a Company commanded by Captain John Richard St Leger Aldworth, of Newmarket in Cork.

As Allshire and his comrades prepared to disembark their ship at Sword Beach, it was hit by a German shell, but it miraculously failed to explode.

Noticing that the first among them had a difficult time getting ashore, because they were weighed down with their backpacks and bicycles - and some almost drowned - Jack and other members of the unit hurled their bicycles over the side and waded ashore without them.

As they came under heavy fire, an officer roared into Jack’s ear: “There are only two sort of people on this beach; those who are dead, and those who are going to die - so get off it now!”

Later, as they moved inland, Corkman Captain Aldworth was killed in a German ambush - there is a memorial to him in St Fin Barre’s Cathedral - and Jack was shot in the leg, ending his war.

Out at sea, Patrick McCarthy, of Bantry, was with the Royal Navy, helping to land the Allied troops, an action for which he was awarded the French Star.

Up in the skies, David ‘Lummy’ Lord, of the RAF, was dropping airborne troops into the fray. He was to die a few months later, aged 31, when his plane was hit as he parachuted supplies into Arnhem.

Also on the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944, was Jack Mahony, of Ballintotis, near Castlemartyr, who went on to be wounded twice on forays inland. He lived to see 100 and also received the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.

Meanwhile, nun Kathleen Walsh, from Blarney, was among those liberated from the Nazis after D-Day, when Canadian forces secured her convent near Laval.

“The return of an All-Ireland winning team would be in the shade compared to it,” Kathleen later said of the experience.

Then there is the remarkable story of Merchant Navy seaman Sean Walsh, of Blackrock, Cork, who had a grandstand view of D-day after he was left alone, stranded out at sea, on a scuppered vessel for ten days!

Perhaps he glimpsed the vessel carrying James Downey, a member of the Royal Navy off Normandy, who was from the Old Head of Kinsale.

Alas, this week, the BBC in the UK, including Northern Ireland, paid fulsome tribute to their D-Day heroes. Here in Ireland, in death as in life, our brave ‘few’ are largely forgotten.

App?

App?