Nostalgia: Development of Cork city allowed citizens to stroll

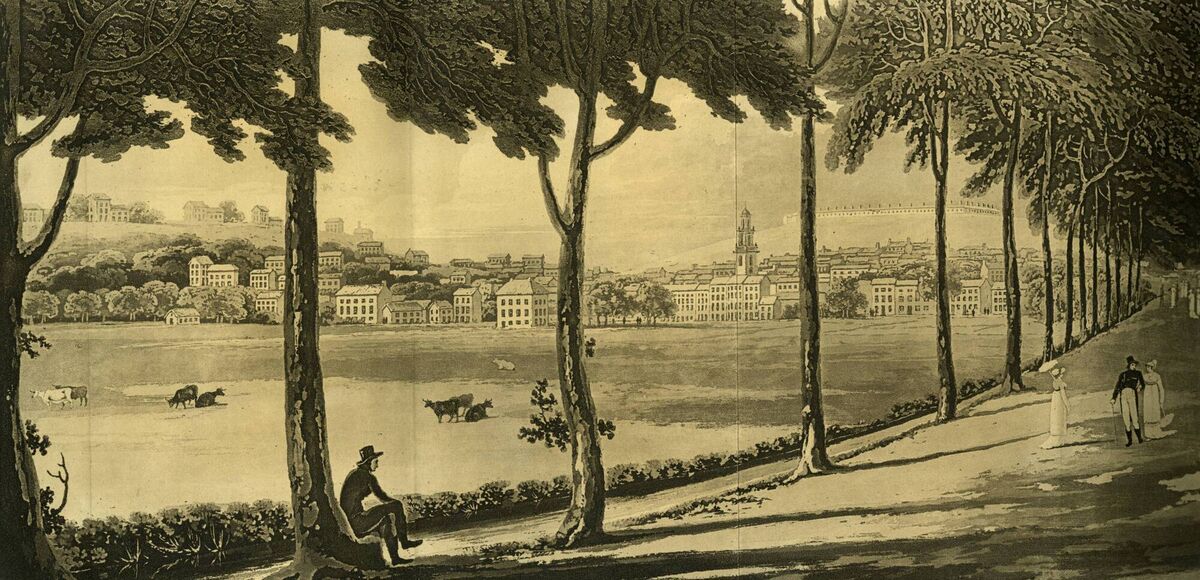

View of the Marina, Cork in 1931.

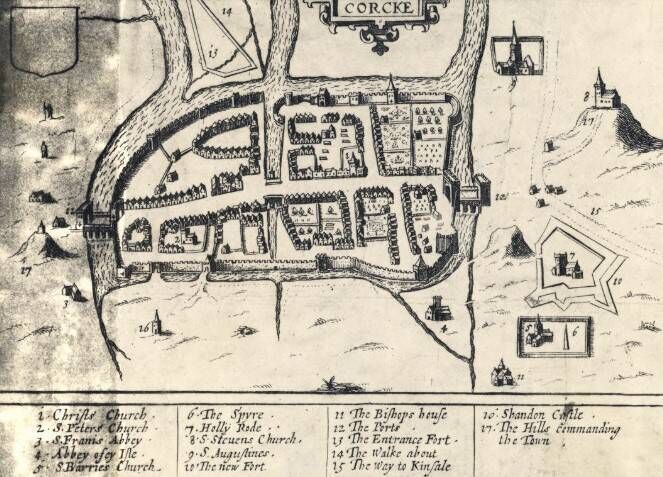

IN the medieval Walled City of Cork, its citizens had very little room to stretch their legs. It was a small place, extending from North Gate to South Gate and from today’s Cornmarket St to Grattan St, covering an area of approximately 36 acres with little scope within its confines for a public walk.

Although for a large part of its history the city found itself surrounded by Irish enemies and English rebels, there were also many years of peace when its citizens ventured outside the walls to take a stroll and enjoy the fresh air. But there was always a great need for a public walk, where the citizens could parade and discuss their affairs.

By the 17th century, the walled city was no longer big enough to contain the continually growing population.

While the ancient wooded forests on the northern and southern hills were quickly being replaced with mud cabins, timber huts, and stone buildings, some of the wealthy merchant families saw an opportunity to develop the prehistoric marshlands situated east and west of the walled city. The Corporation leased these marshes to those merchant families.

Pictorial maps of Cork give us a bird’s eye view of the reclamation. For example, two maps in the Hardiman collection in Trinity College Dublin, one dated 1601 and the other 1602, show that the reclamation had started. We see that the north-east marsh, ie, the area bounded by today’s Paul St, Emmet Place, Lavitt’s Quay and Cornmarket St, this being shown as if embanked (with a building at its south-west corner — on a later map it’s named the fort in the marsh) was known as The Walkabout and was easily accessed by a timber bridge by the citizens of the walled city who wished to avail of some exercise. Some years later, at the eastern end of the marsh, a Custom House was erected on the site of today’s Crawford Art Gallery, Emmett Place.

The ancient east marsh, bounded by today’s South Mall, Patrick’s St, Grand Parade and Parnell Place, was leased to Noblett Dunscombe from the Corporation in the 17th century, and thus became known as Dunscombe’s Marsh. The first physical development that took place there was in the 1680s when it was drained and a Bowling Green was laid out (on the site where the English Market is today) along with gardens with timber structures.

However, these structures were trampled and destroyed during the Siege of Cork in September 1690.

After the Siege sparked a new wave of prosperity for its citizens, a bridge was erected across the ancient shipping channel (todays Grand Parade), connecting Dunscombe’s Marsh with the medieval city and it stood where Berwick Fountain is sited today.

Trees were planted along the eastern side of the dock and it was one of the first parts of the growing city to have its pathway flagged. It was called The Mall and it extended around the corner onto the present-day South Mall, down to Prince’s St; and became a very fashionable promenade for “the gay buck and hooped belle ... on public days is well filled with the beau monde of the city”, wrote historian, Dr Charles Smith.

At the dawn of the 18th century, the physical appearance of the city was changing rapidly and spreading beyond its dilapidated walls eastwards on to the marshes.

The city, however, did not in the first instance extend westwards, although the marshes west of the city wall were purchased by some of the prominent merchants of the city namely: Pike, Hammond, and Fenn and were destined to be developed. The marshes further west, formerly monastic property between the main channels of the Lee, were owned by the Boyles, Earls of Cork, destined to pass to the ducal Devonshires through marriage.

The first attempt to develop the west marsh occurred in 1719 when a committee of the Corporation formed by Edward Webber, town clerk and descendant of a Dutch merchant, were given permission by the Boyles to construct a raised embankment.

This went through their isolated marshlands, westwards from Fenn’s Quay (now Sheares Street) in Hammond’s Marsh to where the Lee divides, destined to be called Devonshire’s Weir, now the property of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC).

After the construction, Webber named it Mardyke after a promenade in Amsterdam called Meer Dyke, meaning a sea-dyke or embankment to arrest the encroachment of the sea. He intended to erect an obelisk at Devonshire’s Weir to terminate the Walk on this 11-acre site.

Instead, he had a teahouse built, the first of its kind in the growing commercial city, with red bricks. In addition, fruit gardens and gravelly pathways were laid out with stone seats placed at intervals where strollers, after promenading along the walk, could partake in a cup of tea and a hot cake and chit-chat.

The draining of the lower city’s south-east marshland occurred in the early years of the 18th century when a solid limestone wall was erected from today’s City Hall eastwards to Blackrock village.

This wall prevented the Lee channel from being choked with silt, making the Lee more navigable. The wall was four feet wide with the river on one side and the slob land on the other and it became known as the Navigation Wall.

A plan was put into place to deepen the channel — a dredger was purchased and silt that was taken from the channel was redeposited behind the wall. The continuing dumping of the mud eventually led to the creation of the Marina as we know it today; and in the 1850s a most beautiful line of elms was planted on both sides of the promenade.

Cork City Library Files

CJF MacCarthy Files

Cork Historical and

Archaeological Society Files

App?

App?