Cork convoy diary: Battles with exhaustion as group take turns driving their cargo of aid across continent

At mid-afternoon on Thursday the convoy is halfway across Germany, in glorious spring sunshine.

Cork Humanitarian Aid Ireland’s convoy left Cherbourg about 4pm on Wednesday and drove until after 1am, when, exhaustion threatening some of us, we stopped at an Ibis outside Charleroi Airport. We felt the better at dawn for the sleep.

As I write, it is mid-afternoon on Thursday and we are halfway across Germany, in glorious spring sunshine.

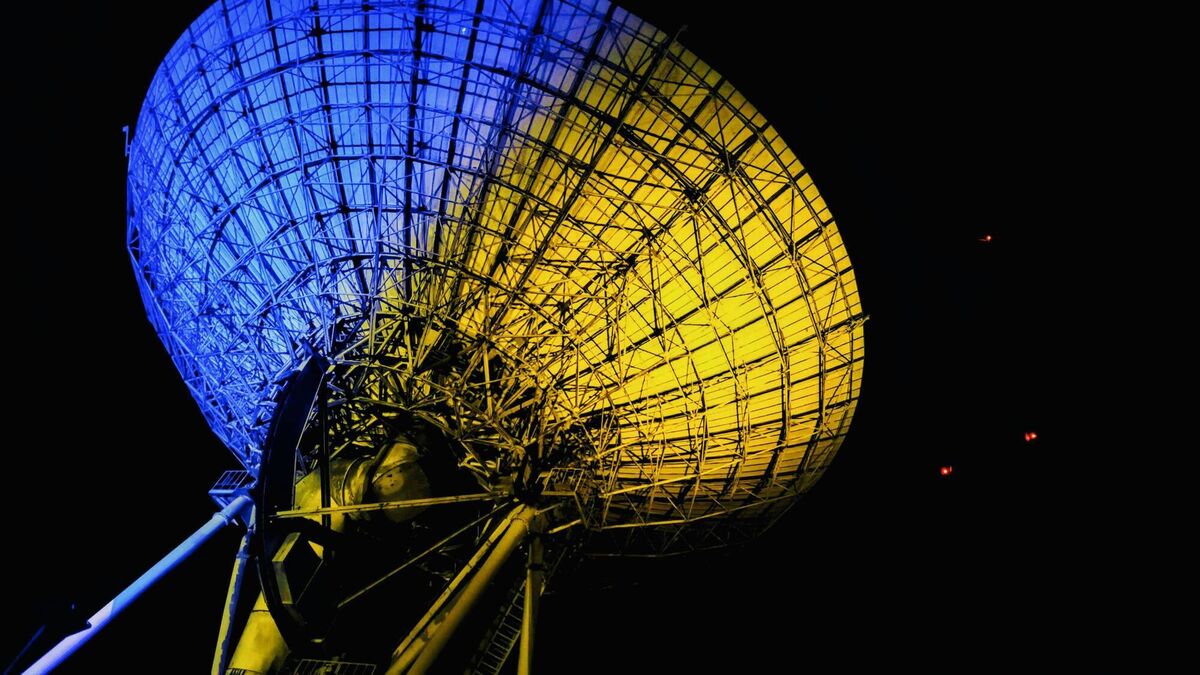

As we travel, word comes from The Echo that the National Space Centre in Midleton has lit up in the Ukrainian colours of blue and yellow to show support for the convoy. When I radio back the line (I’m in the middle van, and Caitriona Twomey of Penny Dinners is in the last van) Caitriona replies that that is a really lovely gesture.

“Every light that shines is a beacon of hope to everyone who is struggling to get to safety in Ukraine, and it means a lot to us on the convoy that people back home are thinking of us,” she says.

A lengthy discussion follows over the radio as everyone else chimes in to joke about “spacers” on the trip.

It cheers up the afternoon for us.

Yesterday, as we drove through France’s flat and beautiful countryside, Scottish songwriter Eric Bogle’s “No Man’s Land” (or “The Green Fields of France”) came to mind, We passed the turn-off for Omaha Beach, and thought of the young men who died there, and the old men who came back a lifetime later to honour those left behind. Later, as we skirted Paris, we saw the sign for Mons, one of the many places angels were said to have sanctified the fields of the Great War.

With any knowledge of history, Europe can seem a weary landscape, and the memory of the cattle-trucks is still strong, the echoes of war ringing from sign-posts. How many refugees travelled these lands over the centuries?

In Ireland, it’s only 175 years since Victorian indifference and ideology conspired to turn a natural disaster into a man-made catastrophe, when those of us starving who still had strength took to the roads.

In Cork, in 1847, an Adelaide Street soup kitchen struggled to pump out 1,400 meals a day, diverting steam from Ebenezer Pike’s adjacent shipyard to heat vats of soup.

Legend has it the Quakers charged a penny for a quart of soup and a half-loaf of bread. (Even if the Cork Examiner of 15 March 1888 does report a meeting in the Imperial Hotel to establish at No 5 Drawbridge Street a facility to distribute what were perhaps Cork’s first penny dinners, today is surely a day to print the legend.) In the depths of Black ’47, the worst year of An Gorta Mór, we could not know that in Scullyville, Oklahoma, the Choctaw Nation had gathered to help the starving Irish, raising about $5,000 in today’s money.

These were people who had just endured incredible hardship and who were living in dire poverty themselves. Less than two decades earlier, the Choctaws had become – under Irish-American President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act – the first Native Americans to be forcibly removed from their lands. Through the worst winter on record and a cholera epidemic, 17,000 Choctaw men, women and children were forced to walk the 500 mile Trail of Tears to Oklahoma, 6,000 dying en route.

They had nothing, in large part thanks to one of our own, and they helped us when we were starving.

Over two million refugees have fled the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In Mariupol, they’re burying mothers and babies in mass graves.

As Eric Bogle wrote as he sat by the grave of Willie McBride, killed in the war to end wars, “It all happened again, and again, and again, and again”.

All going well, we should reach the Ukrainian border by 2am on Friday.

App?

App?