I’m the last drisheen maker in all of Ireland

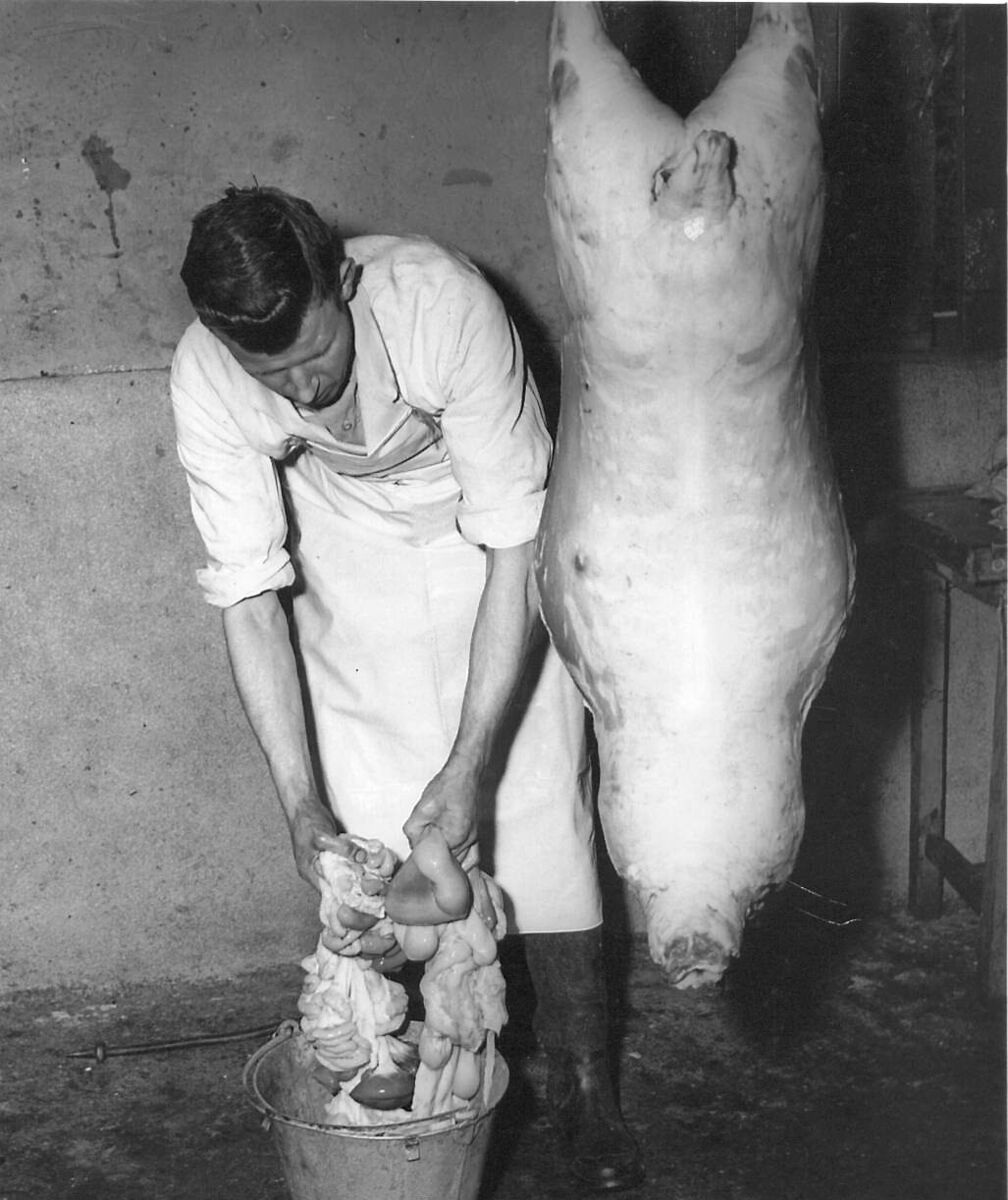

Customers and staff in O’Reilly’s tripe and drisheen stall at the English Market in October, 1959

DONAGH O’Reilly holds a lonely position, as Ireland’s last remaining drisheen maker.

This most Corkonian of all foods has been sold from A. O’Reilly’s stall at The English Market for more than 100 years, and was once one of many Cork drisheen makers.

Each were part of a tradition that has existed for hundreds of years, going back to a time when Cork was a bustling trading port, provisioning ships with barrelled and salted beef, pork, fish, lamb and butter.

Such was the scale of beef production that Cork was once known as the ‘Ox Slaying Capital’, and was a major employer of city folk who were as often paid in offal as money for their efforts.

Out of this meaty exchange of labour rose a strong local tradition and practice of eating offal. From that came production of victuals that met the needs of those with little money to spend on food - drisheen, a type of blood pudding, organ meats (kidneys, liver, sweetbreads), crubeens (pigs trotters), brawn (meat from the head), etc.

Of these, it’s drisheen that is particular to Cork, and to the city specifically.

Drisheen is our Marmite - some love it and eat it weekly, others cannot abide its flavour or texture.

As decades have passed, the eating of it has declined - within a few short years, drisheen could be lost to us forever.

So, what if drisheen is consigned to the history books? If tastes and attitudes have changed so much to where eating drisheen is becoming an ever-vanishing point on the horizon, can the tide be turned to prevent its disappearance?

Regina Sexton, culinary historian at UCC, says: “Foods have a greater turnover of life and death than other items of cultural significance, because they’re perishable - you can’t keep them forever.”

This is obviously true for drisheen, for when Donagh O’Reilly finally decides to call time on O’Reilly’s drisheen, he will draw a veil on an item of Irish food culture specific to Cork and unlikely to resurface again.

I find this concerning. Irish blood pudding traditions, particularly those of Cork, are significant to the city, its history, food culture and heritage.

But let’s start at the beginning, with what may seem like an obvious question: What is drisheen?

It is different to black pudding in one main way. Black pudding is made from whole blood, drisheen is made from a part of blood called serum or, as O’Reilly puts it “the juice”, that is piped into a casing and boiled until set.

So, what is serum, and why is it used to make drisheen?

Blood is made up of liquids and solids. The liquids (or serum) contains lots of protein and nutrients, the solids red and white blood cells and platelets. As fresh blood thickens, it’s cut with a knife and the liquids and solids separate (like curds and whey in cheesemaking), the solids sink to the bottom and the liquids rise to the top.

“I scoop the juice off the top and filter it twice. I add a little bit of salt to it - about 1%, and give it a good stir,” says O’Reilly. It’s then piped into casings, tied off in lengths and cooked in boiling water.

“You have to know by feeling the drisheen if the casing is packed enough, to the right pressure; too much and it will burst in the boiler,” says O’Reilly. “When they’re cooked, they float to the top of the boiler, I probe them [temperature check], cool them fairly quickly, and that’s about it.”

The whole process is very quick: from start to finish a 50kg batch of drisheen is made and cooked in about 30 minutes.

O’Reilly describes the consistency of the protein-rich serum as like an egg white and, just as an egg white will set in a hot pan, so drisheen sets when placed into the boiler to cook.

Drisheen’s unique texture and delicate flavour comes from only using the serum, setting it apart from black pudding in look, taste, texture and aroma.

In times past, three different drisheens were made reflecting a seasonality as such: sheep drisheen, made with sheep’s blood in the spring and summer; beef drisheen, made with a mix of beef and sheep’s blood in the autumn and winter; and tansy drisheen, made with beef blood and flavoured with tansy, a bitter wild herb.

These days, Donagh only uses beef blood and casings to make drisheens, otherwise the recipe is the same for more than a century.

In 1995, Sexton penned an award-winning essay called “I’d ate it like chocolate: the disappearing offal food traditions of Cork City,” which included O’Reilly’s drisheen. For it, she interviewed Stephen O’Reilly, Donagh’s uncle, who ran the stall with Maurice O’Reilly, Donagh’s father, until 2004.

Even by then, the mid-90s, tansy drisheen was already gone and sheep drisheen was starting to fall away for two reasons: the casings were even more delicate to clean and prepare than beef, and changes in the regulations meant getting fresh sheep’s blood was proving ever more difficult.

Changing regulations merged with changes in food attitudes and tastes for Corkonians, says Sexton.

“In my lifetime, I’ve witnessed the stall getting smaller,” she says.

Drisheen carries a stigma people of a certain age and generation want to shake off. As a society becomes affluent, tastes change, and foods linked with hard times are cast aside.

Sexton says it’s debatable if drisheen is unique to Cork - a similar version once made in Limerick is called Packet, also served with tripe. All Packet available these days is Cork drisheen made by O’Reilly’s (the same is true for drisheens sold in Waterford and Kerry), but Sexton is unequivocal regarding its standing as part of Cork’s food culture.

“It is one of Cork’s traditional speciality foods - no doubt about that! What sets Cork apart is the volume of the old cattle slaughtering industry, it was extensive and the volumes of salted beef going out from the port of Cork was absolutely extraordinary.

“That’s why drisheen has a stronger association with Cork, because it’s more ubiquitous and the industry was there to support it.”

That industry was city-centric, which means drisheen is not only a speciality food of Cork, but specifically Cork city.

“It’s that the blood is separated, it’s beef, it’s Cork and it’s connected to the [historical] provisioning industry - all those reasons make drisheen a prime traditional speciality of Cork,” Sexton says.

Drisheen represents much more than a nutritious item of food. It carries with it signposts of Cork’s history and heritage. With that in mind, I ask Sexton if she considers drisheen an endangered food.

“I think it is endangered and, in reality, it probably will disappear,” she says.

So, do Corkonians have a duty to save it? The better question to ask, Sexton says, is why should it be saved?

Do we rescue drisheen because it’s a useful, functional, cheap food (a single serving of drisheen costs €2 today), or because of its association with identity, culture and tradition?

“The whole existence of drisheen as a cheap food to once feed poor people in the city is being flipped completely by those who don’t have to think about spending money on food, and there’s a certain privilege attached to that.

“I don’t think it’s a good thing if [drisheen] disappears, but does it have a function anymore? The function drisheen had, people wanted to leave behind.”

O’Reilly feels a responsibility to keep making drisheen for as long as possible because he is carrying on a family legacy by doing so. But does he consider it a part of Cork’s food culture, and does that weigh on his mind?

“Yes, it does,” he says, “because I often feel as though as soon as I stop making it, that’ll be it, it’s finished. I do feel a certain obligation to keep it going.”

Of course, this is a business for O’Reilly; fortunately, for now, enough drisheen is sold to cover its costs - but only just, and it is no less immune to the current cost-of-living crisis. But O’Reilly has reason to be optimistic.

“I feel as though drisheen is looked over more than it should be. It’s such a nutritionally rich food. You have everything in blood, in everybody and everything. Why wouldn’t it be a good nutrient for people, that’s being overlooked?”

In 1930, English travel writer H.V Morton tried drisheen on a visit to Cork and noted: “[drisheen] is the first thing all doctors in Cork give when you are seriously ill because it the most nourishing and digestible of all foods...”

There are numerous accounts of drisheen eaten for health, supporting O’Reilly’s conviction that it is a food that does you good.

“I think it should be saved,” says O’Reilly, “plenty of people comment they love drisheen, that they haven’t had it for years and they must go into the market and get some, yet they aren’t going in. But if it’s gone, will the same people be saying: ‘Why didn’t I get it while it was still there?’”

Although drisheen is a simple food made with just three ingredients, O’Reilly says the art is in the making of it.

“There were a few women used to work with my dad, Maurice, over the years making the drisheen for him, but I’m the only person in Ireland making drisheen now. It took me a couple of months to master the trade, to get it right. I watched those ladies make drisheen for years, but there was still a bit involved in getting it right - the right flavour and texture - without it bursting.”

“It really is something you have to show somebody how to do, and practice makes perfect!”

Drisheen is a simple, understated food, yet there’s much wrapped up in it. It would be one thing to lose Cork drisheen, but quite another to lose the connection between a food, a place, a history, a people, and the culture that envelopes all of that.

“I remember visiting a butcher,” O’Reilly recalls, “he asked me to bring him out a bit of tripe. I said did he want a bit of drisheen as well and he said, ‘Sure, of course I do - that’s like having bread without butter otherwise’.”

What would Cork be without its drisheen - the bread without its butter? Let’s not consign drisheen to the history books yet. Instead let’s explore how, through new eyes and in new hands, it can appeal to a new generation of Corkonians.

Next week, I talk to Dr Flicka Small, an expert in the use of food in the writings of James Joyce - including drisheen.

App?

App?