Meet the keepers of the flame at Cork’s lighthouses

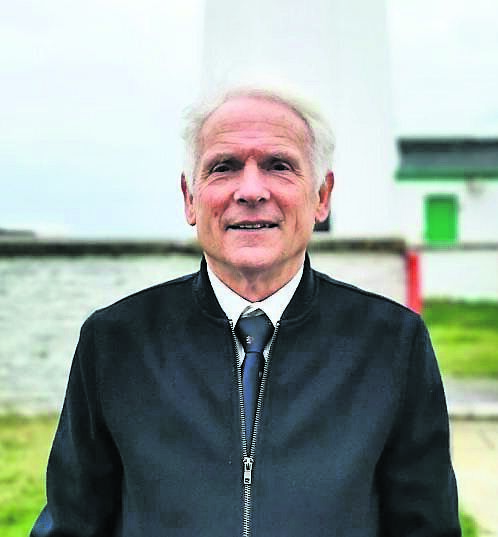

Gerald Butler, from Galley Head Lighthouse, in The National Maritime Museum of Ireland in Dun Laoghaire with the light from Baily Lighthouse in Howth, dating back to 1902.

LIGHTHOUSES served as a primary source of safe navigation for sea vessels navigating the coastal areas.

Since the advent of modern GPS, they are automated and play a secondary role in coastal navigations, but their historical significance remains high - most of all among those who lived and worked or indeed grew up in them.

The Coast of Cork has nine significant Lighthouses, and The Echo are meeting some of them in this series, who still hold a light for their former roles as keepers of the Lighthouses of Cork.

Name of Lighthouse: Galley Head Lighthouse, Rathbarry, Co Cork

Range of Light: 23 Nautical miles

Year built: 1875

Automated since: 1979

Character Night Signal: Five flashes every 20 seconds

Character Day Colour: White

Current Attendant: Gerald Butler.

Gerald Butler was barely four years old when he knew what he wanted to be: a lighthouse keeper. He is one of Ireland’s last.

A twin, he and his brother were born in Castletownbere. His family were stationed there while their father attended the Roancarrigmore Lighthouse, which is today modernised as a guiding light in Bantry Bay.

At age two, Gerald was living at the Galley Head Lighthouse, where he works as a part time attendant today.

His early childhood vocation came to fruition while his father was stationed at Ballycotton Lighthouse, but given that Gerald is a third generation lightkeeper, from both sides of his family, his early calling may not be so surprising.

Public interest in lighthouses and the keepers who maintained them is as rooted within the Irish psyche inasmuch as these striking structures are embedded into the land and rocks from which they sprout.

As islanders, lighthouses tend to stoke up a deep sense of mystique and affinity. We are an island nation, lest we forget.

Speaking from the kitchen where he grew up at the Galley, Gerald agrees.

“Where that has shown itself, is since the automation of lighthouses, since lightkeepers were made redundant,” he says.

“All of this became of great interest. Media became improved, and with that, we became under the notice of the public.

“Suddenly, people were then asking, how did you live out on a rock for a month? How did you live in isolation for a month?”

Since beginning his career at age 19, Gerald has worked on most of the lighthouses of the south coast, from Tearaght Island on the Blaskets right along over as far as Ballycotton.

A 29-year-old Gerald was stationed on the Fastnet Lighthouse on the fateful night of the Fastnet yacht race disaster on August 13, 1979, which resulted in 19 fatalities.

The day prior to the tragedy, Gerald recalls a dense fog, but that the sea was extremely calm.

“On the Sunday, the sea was flat-calm, it was like a pond. It was beautiful. And on the Monday the fog cleared quickly. The wind was jigging around very gently, but it then started to blow up at about three that afternoon.”

By nightfall, a storm raged across the sea, which caused the rudders of many of the vessels involved in the Fastnet Yacht Race to give up. They had made it as far as the Cork coast; in sight of the Fastnet lighthouse, looking east.

Waves reached 50ft in height and the lights of the vessels could be seen tumbling around the high swell. Others vanished from sight, crashing, and flipping into the sea. Loss of life was a certainty.

Gerald and the two fellow keepers, working the Fastnet that night knew this. The radio was frantic with calls for help. All they could do was listen.

“It was awful listening to that. We could not step outside the door. We had all the doors and storm shutters closed up because the sea was rising up so high. There wasn’t a thing we could physically do to help them.

“We also stayed off the radio that night. We did not broadcast of any kind, because the radio was jammed with people crying for help. Our hands were tied. All we could do was listen and continue with our duty.”

Gerald hadn’t experienced anything like that before or since in his career.

After lighthouses were electrified in 1969, and subsequently automated in 1979, a daily physical presence was required for general maintenance, until Gerald was made redundant from full time duty in 1990.

Since then, has worked as a part time attendant at the Galley head Lighthouse and lives nearby in Rathbarry.

These days, the role of attendant requires a minimal amount of day to day managing. Much of the automation technology is operated remotely from the UK.

The attendant’s job at the Galley is a real labour of love for Gerald, who regularly goes over and above what’s expected of him. In 2013, he wrote a book entitled The Lightkeeper: A Memoir.

“It’s a full-time job with part time pay,” he jokes.

Galley head Lighthouse opens its doors to the public twice a year, usually as part of a charity event in May, and in September as part of ‘A taste of West Cork’.

This year, following the lifting of Covid restrictions, Galley Head’s first viewing to the public is on March 18.

The house where Gerald grew up at Galley Head is now in the ownership of the Landmark Trust, and it can be hired as holiday accommodation.

Name of Lighthouse: Roches Point

Range of Light: 21 nautical miles

Year built: 1817

Character Night Signal: White/red every three seconds.

Character day Signal: White Tower

Current Attendant: Jim Power

Whether you’re having a bite at Bunny’s, or a dip in Myrtleville, it can be hard for one to not dart their eyes across the bay to the Roches Point Lighthouse on a bisit.

It beams from the headland. The waters between the coastal diners and dippers, and Roches Point, sees a steady flow of freight vessels going to and fro from the port of Cork.

When Jim Power became a lightkeeper in 1965, the vessels coming in and out of Cork harbour solely relied on lighthouses for guidance. But as GPS was developing from the 1980s and into the early 1990s, lighthouses slowly but surely became a secondary navigation tool for seafarers.

Much of the day-to day running of the building is now automated. A human presence is still required at lighthouses on a part-time basis.

While modern GPS is the most sophisticated navigation system in the world, failure is possible, and electronic equipment on board a vessel may fail, which would render lighthouses the primary source of navigation for a vessel in trouble.

Jim grew up in Whitegate - the East Cork coastal village was at the centre of all this marine activity, and a young Jim absorbed it all.

We met at the Roches Point Lighthouse on the day of his 75th birthday

“When I was about eight or nine, I remember looking across to Cobh,” says Jim. “About halfway across was what was called the Whitegate Road steads and there were a lot of trawlers anchored from a storm. That really stuck with me. I was very interested in why they were there, and that led to me wanting to be a lighthouse keeper.

“The other thing, of course, was the sound of the fog signal during the bad fog.

Through a relative who worked in Irish lights, Jim ended up living at a fog signal station for a few years east of Roches Point called Power Head.

“That informed me even further to say, I would like to be a Lighthouse Keeper,” Jim says.

A 30-year career saw him working in lighthouses all around the country.

“I came to Roches Point in 1989 and the station was de-manned on March 21, 1995. And since the following day, I have been the attendant here.

“These days I come out to check the lights and see that everything is working, and I’ll always come here after storms and things like that,” Jim says.

He, too, was working on the night of the Fastnet disaster. He was stationed on Ballycotton and he and his fellow keepers could only listen to the cries over the crackly airwaves and hear the tragedies live as they were happening.

“We could hear that one couple were trying to climb from a yacht and up onto a ship or something and then a wave took them away. There were three of us listening to that. It wasn’t nice,” Jim recalls sadly.

But for him and his fellow ex-lightkeepers, their memories are by and large positive. There is a great camaraderie between them all. Many of them met each other communicating over the air waves long before they met in person.

There are no plans at present to open the Roches Point Lighthouse to the public, but should that day ever come, visitors would enjoy vast views of the east coast of Cork, while gaining insights into the inner workings of one of the most significant historical buildings in Cork.

App?

App?