Remembering golden summer days in the wilds of Cork’s Glen

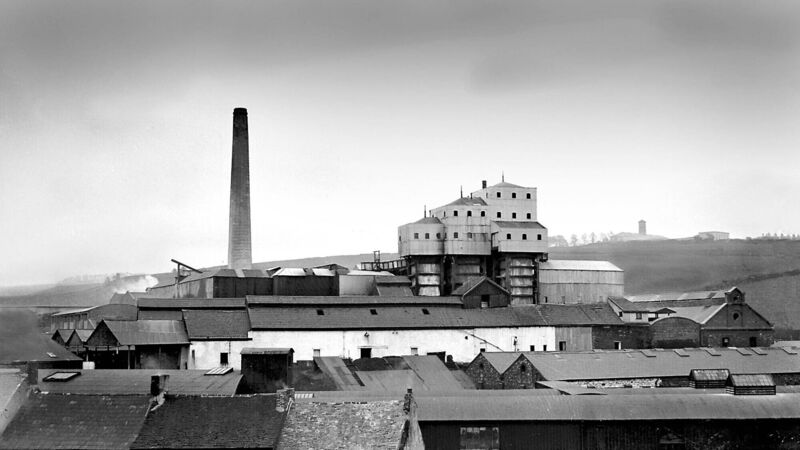

Gouldings factory in Blackpool, Cork, in May, 1929. The large fertilizer factory was built here in the 1850s and was later demolished, but lent its name to Gouldings Glen

WE are into the month of May and all around flowers are springing up, trees are opening their new green leaves, and the grass is growing like crazy. Lambs are gambolling, baby rabbits exploring, and schoolkids yearning for the still far off summer holidays.

If you were fortunate enough to be born on the northside of the city, did you ever go exploring and having adventures in Goulding’s Glen during those self-same summer holidays?

The history of this children’s wild wonderland goes back a long way. Right back to the Ice Age in fact, when a glacial valley was carved out by the waters making their way to the sea, and thereafter the glen which resulted from this ancient and powerful force of nature became the route of a river.

The Glen River still flows east-west to join the Bride and the Kilnap in the Blackpool valley. Together they form the Kiln River which, as every Corkonian knows, flows down to join the Lee near the legendary Poweraddy Harbour.

Today, the area is elegantly entitled The Glen Amenity Park, but for children growing up in the earlier part of the 20th century, it was a place where all your fantasies of exploration, adventure, and excitement could take place on the endless summer days of long ago. (It had its share of excitement too in winter, but that’s another story for another time.)

Why Goulding’s Glen? Well, that family built a large fertiliser factory here in the 1850s, and the name inevitably transferred to encompass the whole area.

The kids who played here were always aware of the strong aroma emanating from that factory but never minded it. It was all part of the Glen experience.

Later, when Goulding’s moved down to the Marina, the Glen factory was demolished, but the name stayed.

In the late 1960s, the land was donated to the people of Cork by Sir Basil Goulding, ensuring that it would remain an oasis of greenery for all time.

Of course it’s been encroached upon, built around, developed around, and where your parents or grandparents could look out over the green hills of Cork, today you see acres of rooftops, housing estates, fast tarmac throughways. But the heart of the Glen still remains.

Back in the day, it was actually quite an industrial stronghold, due in no small part to the plentiful water supply available from the Glen River.

At one time there were at least six factories in full production here, as Gerard O’Brien notes in his wonderful book, Faeries, Felons and Fine Gentlemen (available from his website, Bluehorsepress, and we think you might find a copy in Vibes & Scribes too):

“Six mills once punctuated the valley that is the Glen River Park today: four corn mills, a flax mill, and an iron mill,” wrote O’Brien. “In 1803, a distillery was added, and it later became Goulding’s first fertiliser factory in 1856. Glen Distillery was in operation for at least a century before JH Sugrue took it over in 1884.

“Under Sugrue, the Glen Distillery produced high-quality whiskey which was distributed worldwide, and by 1890 the annual output was 60,000 gallons.”

O’Brien’s father worked for Gouldings when the firm was still located in the Glen, and his family lived in one of just three houses that were located in that very setting.

Now, we know one of the others was the home of Aloys Fleischmann and his family - can anybody identify the third?

Tim Cramer, who grew up on the laneway which led into the Glen back in the 1940s, remembered hearing the factory workers making their way down from Dillon’s Cross past his house and across the Glen to Goulding’s vast establishment.

They were often joined by the cheerful girl workers at Sunbeam, further down in Blackpool, who found this a pleasant way to get to their machines on time, especially on sunny summer days.

Dwyer’s, later Sunbeam, was actually founded on that old flax mill which had been operating for generations before.

Another recorder of the old days of Cork, Liam O’Murchu, spoke in Black Cat In The Window (Collins Press) of his mother leaving school to work at that flax mill when still only a young girl. He makes the point that, despite the bad press given to mills and factories, his mother in fact enjoyed her time there tremendously, making many friends and being able to earn money for the first time.

The Glen played its part in troubled times too. On December 11, 1920, a six-man IRA squad ambushed a convoy of the Auxiliaries at Dillon’s Cross, afterwards making their escape through the Glen.

Sean Healy, one of that ambush squad, afterwards described their escape: “It was now a case of every man for himself to try and make a safe getaway. Under cover of darkness, and hugging the walls, we ran towards Goulding’s Glen and reached it in safety. A large stream ran through The Glen. This was swollen by the winter rains. We crossed the bridge over the stream and got away into the open country by Blackpool…”

(One is reminded of that daring escape by Tom Barry’s West Cork brigade from the pursuing forces over the mountains at night, descending at risk of life and limb into the welcoming safety of Gougane Barra.)

In the Dillon’s Cross ambush, the English forces even used bloodhounds to track down the perpetrators, but to no avail (crossing a river is always a good way to throw dogs off the scent - literally). But it was this ambush which led to the burning of Cork in retaliation.

That master of the short story, Frank O’Connor, grew up between St Luke’s and Dillon’s Cross, and never forgot the place of his birth.

In The Ugly Duckling, he describes his return home in later years, when he “was suddenly plunged back into the world of his childhood and youth, wandering like a ghost from street to street, from pub to pub, from old friend to old friend, resurrecting other ghosts in a mood that was half anguish, half delight. He walked out to Blackpool and up ‘Goulding’s Glen’, only to find that the big mill pond had all dried up, and sat on the pond remembering winter days when he was a child and the pond was full of skaters, and summer nights when it was full of stars.”

Today, the once wild and adventurous Glen is pretty firmly tamed, with firm footpaths and benches on which to take a break, and frequent interpretative events organised for the public. It is not, though, the Glen remembered by generations of children who spent their summer days there, exploring, fishing, paddling, finding out all about the world of nature and adventure.

One such is Tim Cagney, who has given us a heart-warming story full of the delights of yesteryear, when a bent pin, string, and a stick could provide hours, indeed days, of pleasure.

“Growing up on Gardiners Hill, in the ’50s and ’60s, one of the many delights I enjoyed was a visit to the Glen,” said Tim.

“Located adjacent to Ballyhooley Road, it comprised an area of rolling green slopes, forming a shallow valley. At the bottom of the valley ran a stream, home to countless numbers of thorneens. Equally countless numbers of children spent much time there, catching them and bringing them home in jars. The jars consisted, in the main, of the 1-lb jampot type, with loops of string tied around the necks, to facilitate carriage. The strings were usually applied by our mothers.

“The method of catching our aquatic quarry was quite simple - a handkerchief would be fashioned into a hammock-like shape, which would then be scooped-under the grass overhanging the banks of the stream, trapping the unsuspecting fish hiding beneath. The creatures would then be placed in the water-filled jars and carried proudly home.

“Unfortunately, most of said captives would be dead, usually within about a week. The reason was simple - they had consumed all of the oxygen in the water and - effectively - suffocated.

“As children, of course, we had little knowledge of the mechanics of piscatorial respiration, and so the matter of such mass demise remained a mystery.

“One day, however, a friend of mine - called Paddy - caught a thorneen which bucked the trend. To start, he appeared slightly larger than the usual specimens we captured, so much so that, when Paddy got him home, he had to transfer him to a larger 2-lb jar.

“Paddy decided that the standard diet of breadcrumbs most of us fed our thorneens was just not good enough, and so he fed his fish with worms, dug-up from his garden and diced. He also insisted on changing the water daily, unwittingly providing his captive with a constant supply of fresh oxygen. (Paddy, incidentally, became an engineer later in life).

“Not alone did the thorneen refuse to die, he actually began to grow larger. It soon became apparent that even the 2-lb jar was not large enough to hold him, so Paddy sought help from his mother. She kindly supplied him with a mixing-bowl, one of those enormous brown earthenware things, usually used for preparing Christmas cakes and puddings.

“The mother - most likely - reckoned that, by the time Christmas rolled around, the creature would be long-dead, and the bowl could be retrieved for its original culinary purpose. At around this time, Paddy decided to name the fish Thomas.

“Thomas continued to thrive in his capacious new home, growing ever-larger. Then, one day, Paddy found himself facing a dilemma - the family were due to go to Crosshaven, for their summer holidays, and Thomas would be left alone.

“By this time, he had established somewhat of a bond with Thomas, and he had no desire to see him die in a pudding-bowl. Only one thing for it - he would return Thomas to the wild.

“And so, there came the day that we loaded Thomas into a 2-lb jar, in order to carry him back to the Glen. By then, the fish was so large that his tail protruded above the water-line, but we reckoned he would be robust enough to survive the journey.

“We arrived at the stream, and lowered the jar beneath the water. Somewhat hesitantly, Thomas wriggled (backwards) out of the receptacle and then, with a quick turn of his tail, disappeared into the depths from whence he had come.

“Paddy and I carried the empty jar back to Gardiners Hill, hearts aglow at having performed what we considered a noble deed. We would never again meet the likes of Thomas.”

We should perhaps emphasise that the portrait here was executed at a time when Thomas was still a fairly young thorneen - only a thraneen, so to speak.

He has, undoubtedly, grown much since that time, and is probably a venerable grandfather of many, many little thorneens of the Glen today.

If you’re passing that way in the summer months ahead, salute any fish you might see in a stream. If it isn’t Thomas himself, he will probably know him. As you tend to do in the Glen.

Got your own memories of the Glen? Share them with our readers! Email jokerrigan1@ gmail.com. Or leave a comment on our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/echolivecork.

More in this section