Cork tragedy that led to birth of fire brigade

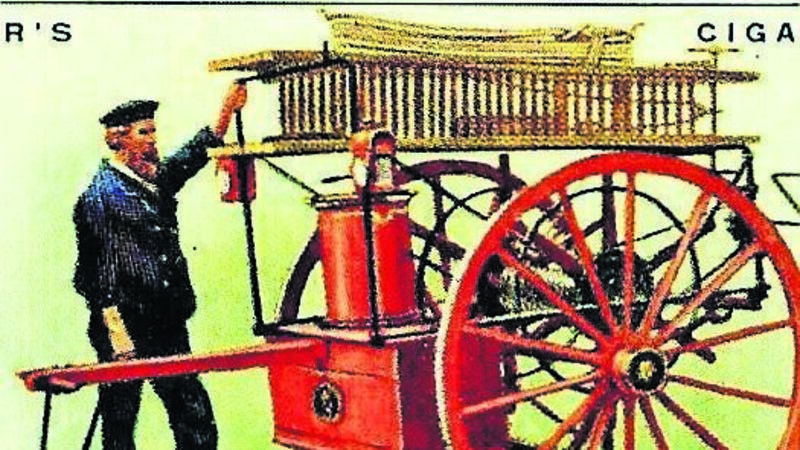

A ‘Hose and Ladder’ carriage similar to that operated by the city Water Inspectors in 1874

LATE on the bitterly cold night of October 19, 1877, the inhabitants of Cork city’s southside were startled by the sudden blare of what sounded like a lighthouse foghorn.

Perplexed, many ran to their front doors to ascertain the source of the unusual racket. Immediately, however, they were distracted by something far more tangible: a frightening glare in the sky in the north-eastern quarter of the city. As the eerie cacophony from the foghorn continued, the word soon went around: Cunningham’s Provision Stores on Merchants’ Quay, a complex stretching from Patrick’s Street back to Parnell Place (think Merchants’ Quay Shopping Mall), was on fire!

The foghorn - for that is what it was - had been installed in the fire station on Sullivan’s Quay (then little more than an open yard with an office) to summon members of the newly-created Fire Brigade when an alarm call was received.

Now, the tiny, untried unit was turning out to its very first call; a task that, even today, would tax the resources of a modern brigade.

Remarkably, the little party comprising just four firemen and their Superintendent, Mark Wickham, acquitted itself very well.

Praise for their efforts was led by the Cork Examiner. Indeed, for many years, the campaign for the establishment of a firefighting force in the city had been spearheaded by the newspaper under its founder, John Francis Maguire, Mayor, Member of Parliament, and staunch defender of Catholic and Nationalist rights. Despite a series of huge fires, many with loss of life, the City Fathers at every hand’s turn thwarted Maguire’s efforts. The addition of a half-penny on the rates to fund such a service could simply not bear thinking about.

By 1877, however, the scandalous situation could no longer be ignored and, grudgingly, the decision was made to establish Cork Fire Brigade ‘provided it could be done for less than £500 a year’.

Sadly, Maguire, who had fought long and hard for such a day, did not live to see the project dear to his heart come to fruition. He passed away in 1872.

Of all the fires leading up to the decision to form the brigade, many agreed it was a horrific one on the Grand Parade, three years’ earlier in 1874, which unfolded before the eyes of thousands of spellbound onlookers, that proved the catalyst for the Corporation’s change of heart.

******

Mary O’Callaghan was a worried woman. As she hurried along the street on her way to the Courthouse accompanied by her lodger, Hannah Flint, she wore a deep frown. Just one week since, two soldiers from Cork Barracks had entered her draper’s shop at Daunt’s Square - close to Woodford, Bourne’s - and, while one had kept the staff distracted, the other had been busy helping himself to some items of clothing.

They were spotted and ran off, the shop assistants pursuing them hot foot along Patrick Street. Some policemen took up the chase, and the duo were hauled, kicking, and screaming, to the Bridewell. It took six policemen to subdue them, and as they were dragged past O’Callaghan’s shop they cursed and swore revenge. If they were gaoled, they shouted, their comrades would take revenge.

Thus, that Friday morning, October 16, 1874, she quickly blessed herself passing St Augustine’s, head bowed against the bitter black wind blowing down the Western Road from the Boggeragh’s, and fervently whispered a quiet aspiration to her late husband to give her the strength to carry her through the day.

As the morning’s court cases wore on, the sheer tediousness of it all did nothing to pacify her state of mind. She had to force herself to avert her eyes from the malevolent glare of the two accused, seated between two policemen.

Then, just as the case was about to be called, she jumped, startled, as a policeman tapped her urgently on the shoulder. Would she mind stepping outside for a minute?

******

Standing on the top of the courthouse steps, Mary gazed in dismay at the roiling clouds of dense, black smoke gathering over the northern end of the Grand Parade, which told their own story. As she ran like the wind back to her blazing premises, the frightful curses of the two soldiers rang in her ears. She was only vaguely aware of the Angelus bells booming out their call to prayer across the noonday city.

Daunt’s Square was a bedlam of confusion: of shouting, screaming and the crackling of flames. The crowd, already hundreds deep, stood as if riveted, watching flames spectacularly leaping from window to window up the façade of O’Callaghan’s. Then, to their disbelief, a little old lady appeared at a window of the third floor and began to climb out.

Recounted the Cork Examiner: “Exclamations of horror and prayers for her safety burst simultaneously from the crowd below.”

The fire was discovered some time after 11.30am by the shop assistants.

Investigating a strange smell, they opened the door of the ground floor ‘oil room’ adjacent to the stairs and were confronted by a mass of flames.

Not alone did they not take the simple precaution of closing the door to the room on fire, but they made another fatal mistake. Reacting automatically in the way they had done a thousand times before when leaving the shop unattended, they locked the door onto the street while making good their own escape. In doing so, they sealed the fate of the five people remaining on the upper floors of the building.

In that room, an insidious, deadly transformation had occurred. The fire in the closed room had, without sufficient air, burned quietly for a time, during which it gradually heated the contents to their ignition temperature. When the door was opened, the fire, suddenly satiated with life-giving oxygen, quickly spread over the whole room in the dreaded phenomenon known as a ‘flashover’.

As the flames, toxic smoke and superheated gases raced up the narrow funnel of the stairs, Arthur Flint, a 39-year-old marine dealer, swiftly considered his position. Gathering up his little daughter and son under his arms, and grabbing Mary Walsh, Mrs O’Callaghan’s elderly servant, he decided to make a dash for it down the stairs. It was a fatal mistake.

Meanwhile, on the top floor, Eliza Grogan was climbing out onto the windowsill.

******

Alderman John Jones was among the first to spot her predicament. Calling on some men to help him, he sprinted down the Grand Parade to the English Market to procure a ladder. But, when fully extended, it fell 5ft short of Mrs Grogan’s window.

But, ‘Cometh the hour, cometh the man’. Sizing up the situation, a young slater from Douglas Street, William Kavanagh, skillfully climbed the ladder, guided the old lady’s feet onto the uppermost rounds, and, amid great cheering, brought her to safety.

Eliza was the only one of the trapped occupants to escape entirely unharmed. She later explained that, at the first sign of trouble, and realising the stairs were impassable, she had closed her bedroom door - thus inhibiting the ingress of poisonous smoke and gases - and gone to the window to cry for help. Although she had to wait some 15 minutes for the ladder to arrive, her actions saved her life.

The Flint party was less fortunate. Poor Arthur, who had sucked flames and superheated gases down through his bronchial passages, on reaching the foot of the stairs with his charges - all hideously burned - found the hall door locked. All collapsed, unconscious, just feet from the street. There they lay, their lives ebbing away, until Corporation Street Inspector Denis Lyons kicked in the door, and they were dragged out. Arthur Flint, his son, and Mary Walsh all died from their awful ordeal.

In the confusion, the little boy was initially missed. His charred remains were later discovered by the Mayor himself. The little girl lay critically ill at the North Infirmary.

It was the single greatest loss of life from fire in Cork for many years, made even more shocking by the fact it had taken place in broad daylight, the horror unfolding before thousands of horrified Corkonians.

Previous fatal fires had mostly occurred late at night or in the early hours, witnessed by few.

The cause of the fire was never established. The fact that the soldiers’ comrades had sworn revenge was taken seriously, but nothing was ever proved.

******

On the firefighting front that day, there was the usual interminable delay while the Corporation Office at 20, South Mall was informed. Before the Fire Brigade was established, firefighting duties were performed by the staff of the Water Department, whose ordinary work took them all over the city. Messengers had to be sent to notify them wherever they could be found.

When, eventually, the fire hydrants were put to work, the pressure was so poor that the water splashed uselessly off the windows of the burning building.

As the Cork Examiner narrated: “A volley of stones and broken bottles was directed at the windows to break them, and the desired result was very soon accomplished with the able assistance of a few Cork marksmen.”

William Kavanagh, who had conducted himself so courageously throughout the incident (he made several sorties off the head of the ladder trying to locate the victims), applied to the Corporation for compensation for his destroyed clothing, boots and personal effects to the amount of £6.16s.0d. Rather than commend the young man for his tireless, heroic efforts, an undignified public wrangle ensued, a number of City Fathers dismissing out of hand the awarding of any such payments. Go to the insurance companies for your money, he was told.

Eventually, grudgingly, Kavanagh was given £5.

******

Cork City Fire Brigade has, for the past 145 years, been ‘Protecting, Preventing and Responding’ to the emergency needs of the citizens, evolving and developing in tandem with the great ‘Rebel City’ itself.

Its role is changing, however, from being purely ‘response’ to ‘mitigation’, too. The emphasis now is to work closely with the community in the reduction of hazards, while at the same time enhancing its ability to respond to emergencies of all kinds.

In its early days, the brigade had its ‘Mission Statement’ emblazoned along the back of its appliances: ‘Semper Paratus’ - ‘Always Ready’.

That much, at least, remains unchanged.

The final part in Pat Poland’s trilogy on the history of the fire and rescue service in Cork city is available now. entitled Cork City Firefighters: A Proud Record. A Visual History From 1950, it contains more than 240 black and white and colour illustrations.