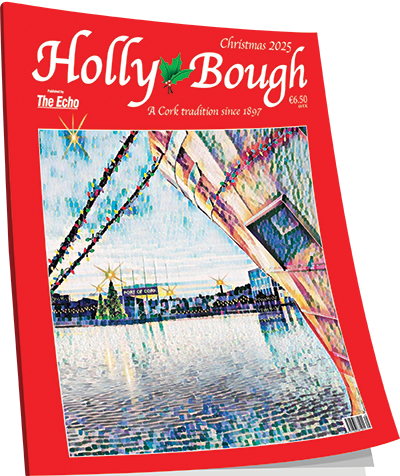

Bookish David McCullagh is ready for his new radio role

Writer and broadcaster David McCullagh at the launch of his new book, From Crown to Harp.

A 1921 cartoon from Punch features in David McCullagh’s new book, .

It depicts an Irish nationalist asking an innkeeper whether the hostelry is called the Harp. The landlord genially replies: “ and Harp, sir, but I don’t think you’ll find it any less comfortable for that.”

David McCullagh says the cartoon encapsulates British thinking at the time of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

“That is exactly the British attitude, that the addition of the crown is not going to make any practical difference, but it gives us that little symbolic thing to cover the fact that we are surrendering control of 26 counties in Ireland.

When we meet for sandwiches and coffee in Market Lane on Oliver Plunkett St, the writer and broadcaster is on a visit to RTÉ Cork for an appearance on .

We chat about his new book - “a must-buy for Christmas,” he deadpans - and his new RTÉ Radio 1 show, , which starts at 9am on Monday.

He says he wrote the book during a “handy” bout of insomnia, getting up at 5am to work on it, and building upon research he had done for previous biographies of Éamon de Valera and John A Costello.

“They were quite prepared for the new Irish Free State to have as much practical independence as it wanted, but they insisted on keeping that symbolic link, which was anathema to any Irish republican, after the sacrifices of the War of Independence.

“The British and the anti-Treaty republicans assumed that the Treaty was going to last, if not forever, at least for generations,” he says.

Collins didn’t like the Treaty, he says, but recognised that if Ireland became a dominion, the other dominions were gradually developing towards independence, and Ireland could ride that wave and gain more independence for itself.

“De Valera’s mistake, I think, in the Treaty debates, was to assume that partition was temporary, but the Treaty settlement was permanent, whereas in fact it was the other way around,” he says.

That was a common mistake, he adds, with everybody in the Dáil assuming “the Boundary Commission was going to do the divil an’ all and make Northern Ireland completely unviable, and that would put an end to partition.

“Of course, they turned out to be incorrect for various reasons, that I go into in the book.”

He says the Treaty debates were “entirely focused on the crown and on the Oath of Allegiance, on this symbolic link to the British crown, which, in practice, meant very little, but which to that revolutionary generation meant everything.

“De Valera’s alternative, external association, accepted that Britain had legitimate strategic needs in Ireland for defence, and he was prepared to offer them that, and he was prepared to offer them a connection between Ireland and Britain, if Ireland would be outside of the Empire, which meant it wouldn’t have to swear allegiance to the British king.

“And that was the Treaty split.”

It is, he says, a historical irony that it was Michael Collins’s political successors in Cumann na nGaeadheal who “did a lot to unlock the padlock on Irish freedom with the Statute of Westminster, which basically was London acknowledging that the dominions could do whatever they wanted, including walk out of the Commonwealth if they so wished, which is hugely important, but Cumann na nGaeadheal thought, ‘Okay, that's all we need, we don’t need to move any further’.

“They removed the padlock. It took de Valera to open the door and to go further with the 1937 constitution, but he retained a tenuous link to the crown with the External Relations Act, under which Irish diplomats had their letters of accreditation signed by the British king.

“He did that partly to avoid trouble with London, partly to avoid a renewal or an intensification of the Economic War, but mainly to provide a path back to unity on the island of Ireland, in recognising that if unionists ever came back into a United Ireland, there would have to be some kind of a link with the crown, no matter how tenuous.”

It then took another change of government, he says, for John A Costello to “actually walk through the door”, declaring a republic in 1949.

There are ironies and inconsistencies on all sides, he says, in what he sees as a fascinating story.

“Winston Churchill said the Treaty settlement would stand for all time as the relationship between these two islands, and he was out a bit because it only stood for 28 years, and it was undone, unravelled, removed, without a shot being fired, without any violence, without anybody having to wade through anybody’s blood. And I think in terms of a sustained campaign of diplomacy, it was unrivalled.”

Even if David McCullagh, a Dubliner through and through, has no Cork connections – “None whatsoever,” he cheerfully declares - there is a Cork connection to the story of Ireland’s sovereignty.

“The moment when de Valera achieved full sovereignty in the 26 counties was the moment he stepped off the tender at Cobh in 1938 to see the handover from the British to the Irish of the Treaty ports,” he says.

“Cobh was first, Berehaven was second, and Lough Swilly was third.

“Dev spoke sometimes about when he was going to America in the 20s, and he’d get on the liner to go across the Atlantic, and they’d have to pass the port with the British flags flying, British troops there, and he said as long as that was the case, we did not have full sovereignty in the 26 counties.

“The handing over of the ports was hugely significant because it meant that Ireland could remain neutral in the Second World War, which would have been impossible if the British had still been in occupation of the ports.

“He was able to say, ‘We now control every square inch of the 26 counties,’ and then obviously went on say: ‘We fervently hope that we will be controlling the other six counties in short order'.

“That was an absolutely massive moment.”

The presenter has a significant enough moment himself on Monday, when he takes over from Claire Byrne on the show.

“Yeah, I'm really looking forward to it. I was in at a meeting the other day about our plans - which I'm not going to share with you - but they played the amended jingle for . That was kind of a moment,” he concedes.

Having studied history and politics in UCD, his journalism career began in 1989 at the . He joined RTÉ in 1993, becoming its political correspondent in 2001. He presented from 2013, moving to the in 2020.

He is probably Ireland’s most high-profile Bruce Springsteen fan, having seen the Boss 41 times and counting, and friends say is the odds-on favourite to be the first tune he plays during his new gig.

“The new job is really exciting, because it’ll be a different sort of challenge for me, covering a lot of topics that wouldn’t generally come up in news programming," he says.

“It can be a lot of fun, and I’m hoping that the listeners will feel that it’s fun as well.”

App?

App?