How we covered Ireland's first presidential election in 1945

President Sean T O'Kelly visits the Sunbeam Wolsey factory in Cork in 1948

President Michael D Higgins will complete his second, and constitutionally mandated final, term on Tuesday, November 11. The election to replace him, which must take place within the 60 days before that date, will occur 18 days before the end of his presidency, on Friday, October 24.

Ireland’s first president, Dubhghlas de hÍde, was not elected, but rather was appointed in June 1938 by both Éamon de Valera and the leader of the opposition, WT Cosgrave.

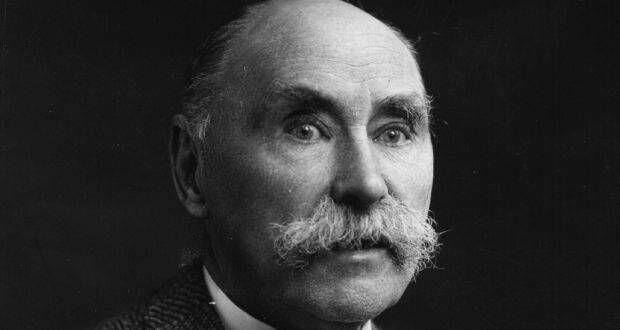

A Protestant, and a very admired and likeable academic, Douglas Hyde, then 78, had been a leading figure in the Gaelic revival, and the first president of the Gaelic League. From Roscommon, Hyde’s people hailed originally from the Castlehyde estate outside Fermoy.

(Nowadays, Castlehyde House is the sometimes residence of Chicago-born dancer Michael Flatley, who has indicated an intention to seek a nomination to run in October’s presidential election.)

With the wounds of the Civil War still very raw, Hyde was nominated because de Valera and Cosgrave wanted him to be a symbol of reconciliation. The fact he had no association with Sinn Féin or the War of Independence probably stood to him in that regard.

Dev and Cosgrave also saw him as obvious proof that Ireland was not exclusively a Catholic State and a reassurance against fears, widespread at the time of the drafting of the 1937 constitution, that the new head of state might become an authoritarian dictator.

Both men thought highly of Hyde, they appreciated all he done to promote the Irish language, and they had regretted that he had not been re-elected in 1925 to the Seanad seat he had only held for seven months.

There was another consideration to their selection. The 1937 constitution was, to put it charitably, less than clear on whether it was the president or the British monarch who was the official head of the Irish State. That would remain a question which would not be answered until the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, when President Hyde’s successor, Seán T O’Kelly, became internationally recognised as Ireland’s head of state.

It probably didn’t hurt that Hyde certainly looked the part of a genial head of state, tweedy, bald, and whiskered, and — wearing formal morning attire, which he absolutely detested — he was inaugurated as the first president of Ireland on June 26, 1938, at a formal ceremony in Dublin Castle.

The then Evening Echo splashed the story with the headline “The First President of Ireland Installed”, and below it a quote: “I ask God for strength and wisdom to fulfil my duties”.

The front page featured a photo of what is now Áras an Uachtaráin: “The former Vice-Regal Lodge in the Phoenix Park… now the official residence of the President of Éire. Inset: Dr Douglas Hyde, the President”.

Our lead story began: “In a ceremony lasting only ten minutes, Dr Douglas Hyde was officially installed, to-day, the first President of Ireland. The President-elect, having attended a Protestant service at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, while a Votive High Mass was being offered in the Catholic Pro-Cathedral, returned to his residence in the formal Vice-Regal Lodge in the Phoenix Park.”

Religious ceremonies were also held at the two principal Methodist and Presbyterian churches, and Dublin’s synagogue.

From his new residence in the park, the president was driven to Dublin Castle, where the formal ceremony of installation took place. Along the way, cheering crowds waved flags and lined the streets, and the presidential procession paused outside the GPO to pay tribute to the patriots of 1916.

When President Hyde arrived at Dublin Castle, “The Taoiseach, Mr de Valera, greeted the new President in the name of the nation, and said, ‘We greet you as the successor of our rightful princes, and in your accession we hail the closing of the breach that existed since the undoing of our nation at Kinsale.’

“President Hyde replied briefly in Irish. ‘I pray God,’ he said, ‘to give me the grace and power, to give me the wisdom and strength that I may fulfil my duty as President of Ireland.’”

Early in his presidency, President Hyde attended an international soccer match between Ireland and Poland at Dalymount Park, breaching the GAA’s ban on foreign games. It cost him his position as the association’s patron, which he had held since 1902.

President Hyde’s time in office was marred by loss, with his wife, Lucy Kurtz, who had been plagued with chronic illness, passing away at the end of 1938, at the age of 77. Her illness meant she was unable to move into Áras an Uachtaráin, staying instead in Ratra, the Hyde family home in Co Roscommon.

Serious ill-health afflicted the president too, and a massive stroke in April 1940 left him paralysed and confined to a wheelchair. When it appeared for a while that the president would not survive his illness, plans for his lying in state and a state funeral were drawn up, before being quietly dropped.

The first president’s time in office was dignified, and conservative, setting the template for the presidency for the next half century.

During his term he referred two bills to the Supreme Court, under Article 26 of the Constitution of Ireland. In the first case, the court held that the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Bill 1940 was not repugnant to the Constitution. In the second reference, the court decided that section 4 of the School Attendance Bill 1942 was repugnant to the Constitution.

One of his last official acts was to remain a secret for 60 years: he visited German ambassador Eduard Hempel to offer his formal condolences on the death of Hitler.

Dubhghlas de hÍde served one term, with his time in office ending on June 24, 1945. He lived out his retirement in the former residence of the secretary to the lord lieutenant, which he renamed Little Ratra, on the grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin. He died on July 12, 1949, aged 89.

The first Irish presidential election took place on June 14, 10 days before Hyde’s term ended.

The day before the election, the Evening Echo’s headline read: “Polling Day for 1¾ Millions: Presidential and Local Elections To-Morrow”. The story ran:

“A very heavy poll is expected to-morrow when about one and three-quarter millions of voters in Éire will have the opportunity of voting for President and for the Local Authorities.

“For the President’s Office, there are three candidates, Mr Sean T O’Kelly, the Minister of Finance, General Mac Eoin and Dr MacCartan.” O’Kelly, the Fianna Fáil candidate, was de Valera’s tánaiste and a 1916 veteran who had fought beside Pearse in the GPO. The Fine Gael candidate, Seán Mac Eoin, was also a War of Independence veteran, while Independent candidate Patrick MacCartan had been due to take part in the 1916 Rising, but did not, thanks to Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order.

Then, as now, under Article 12 of the Constitution, the route to a nomination necessitated either the support of four local authorities or of at least 20 members of the Oireachtas. Dr MacCartan had failed to secure the necessary nominations of four councils, but succeeded in gathering 20 Oireachtas votes.

In a sign of the times, the Echo story shared front-page space with headlines about Russian allegations of brutality at a Scottish prison camp for Polish soldiers, the Japanese government’s plans against an Allied invasion, and a case taken by the British admiralty against the Cunard line over the October 1942 collision between the Cunard liner Queen Mary and the British anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Curacoa off the Donegal coast.

The Evening Echo on polling day had, of course, gone to press that lunchtime, so had to run a hardy perennial of a headline: “Slow Voting in the Elections: Rush of Electors Expected This Evening.” In truth, the reporting could be charitably described as place-holding, something most journalists would defend in the circumstances, but it made up for any shortcoming by being beautifully written.

“Cork’s morning election activity was on the dull side. The booths opened under a leaden sky, and the threat of rain, coupled with the desire to get the job done before the ordinary routine of the day was entered on, was probably responsible for the usual flow of voters in the first hour or so. After this, things quietened off, to liven up somewhat again round the lunch hour. As the afternoon wore on, the presiding officers were kept fairly consistently at work, but all of them expect that their busiest time will be from 6 o’clock onward.”

There followed a description of a scene which has been illegal since the Electoral Act of 1992: “Political parties had their usual representatives inside and the polling stations, each of the latter being clearly discernible by a goodly display of election literature. Polling proceeded smoothly as the day progressed and there was no report of any ‘incident’.

“Our reporter heard one lady decline the offer of election leaflets outside a polling station with the remark ‘I have enough at home already to keep the fire going for twelve months’.”

The next day, our headline was “First Results Put FF Candidate In Lead”, over a story which led with: “The first results in the Presidential election were announced to-day and, so far as available, the figures of the first preference votes show that Mr Seán T O’Kelly, the Fianna Fáil candidate, has a substantial lead.

“The figures up to the present are no more than fractional indications of the voting throughout the whole country. The preliminary reports indicate that General Mac Eoin headed the polls in parts of Sligo and Leitrim, but elsewhere Mr O’Kelly had the lead. Dr MacCartan is a long way behind the other two candidates. Reports from the counting centres state that a large number of his second votes have been cast for General Mac Eoin.”

The next evening, Saturday, a slightly clearer picture was emerging.

“Though the final results of the count in the Presidential election are still awaited, it is apparent from the figures now available that Mr Seán T O’Kelly, the Fianna Fáil nominee, will head the poll.

“Whether he is declared elected in the first preference vote must await the final returns, but with the lead he now holds, his election as President does not appear to be in doubt.”

By Monday afternoon, a second count was underway. “Though the result of the vote in the Presidential election has not yet been officially declared, it is apparent from the figures as already announced that Mr Seán T O’Kelly, the Government’s nominee, will be elected.

“His failure to obtain a return on the first count has necessitated a count of the second preference votes, which is proceeding in Dublin to-day. After the elimination of Dr MacCartan the transfer of votes is regarded as certain to return Mr O’Kelly, who is Finance Minster and Tánaiste.

“His election as President will mean his resignation from the Government and a re-shuffle of Ministerial posts.”

The following day, the war knocked the presidency off the top slot, with the main headline: “All Japan To Be A Fortress: Tokyo Report Of Preparations For Invasion.” Across the page was “The Final Vote For President: Mr O’Kelly Elected By Majority Of 111,700”.

“Mr Seán T O’Kelly’s election to the office of President of Éire was announced at 6.45pm yesterday, by Mr Wilfred Brown, Presidential Returning Officer. The distribution of the second preferences on Dr MacCartan’s papers began at 9.30 in the morning. The distribution of the second preferences took eight hours.

“Immediately the result was announced the Returning Officer handed sealed envelopes containing the result of the poll to seven Army Officers, who delivered them to President Hyde, the President-Elect, the Taoiseach, the Chief Justice, the Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann, the Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann, and the Secretary to the President.”

On Monday, June 25, 1945, the Evening Echo’s lead story began: “After attending a Votive Mass in the Pro-Cathedral to-day, Mr Seán T O’Kelly, the newly-elected President of Éire, made the Presidential declaration at Dublin Castle, and afterwards drove through the streets, which were decorated for the occasion, to the official residence in Phoenix Park, the former Vice-Regal Lodge.

“The President’s declaration, and a welcoming address by An Taoiseach (Mr de Valera) were made in the Irish language. Mr de Valera and the retiring President, Dr Douglas Hyde, who was unable to be present, sent his congratulations and good wishes.”

An inner-city Dubliner and the son of a shoemaker, O’Kelly was one of the founders, in 1905, of Sinn Féin, and during the Rising he fought in the GPO, gazetted a staff captain by Pearse. He was jailed repeatedly in the wake of the Rising, released, rearrested, escaped, and in 1918 he was elected Sinn Féin MP for Dublin College Green.

He served as ceann comhairle of the First Dáil, and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty. A close friend of de Valera, he was jailed during the Civil War until the end of 1923, after which he served for two years as Sinn Féin’s envoy to the US, where he raised funds for the anti-Treaty side.

In 1926, he became a founder member of Fianna Fáil, with Dev appointing him party vice-president. When Fianna Fáil won the 1932 general election, de Valera was elected president of the Executive Council — in essence, taoiseach — and he appointed O’Kelly his vice-president, a position analogous to tánaiste.

O’Kelly earned a reputation as a pugnacious minister for local government, engaging in a campaign of public humiliation against James McNeill, governor general of the Irish Free State, the representative of the British crown.

When McNeill resigned, de Valera was publicly embarrassed and the blame seems to have gone to O’Kelly, who was reportedly surprised when he was passed for the position of McNeill’s replacement. Still, he remained second-in-command, formally becoming tánaiste to Dev’s taoiseach at the enactment of the 1937 constitution.

A famously indiscrete character (the Dictionary of Irish Biography cites his “excessive fondness for whiskey”), O’Kelly’s membership of the Knights of Columbanus irked de Valera, not least because Dev suspected someone in his cabinet was leaking to the Catholic hierarchy.

When he was president, that indiscretion manifested itself in what was to become a notorious incident.

In 1949, on a visit to the Vatican, President O’Kelly managed to irritate both Pope Pius XII and Josef Stalin by sharing with the press the pope’s private views on communism.

In 1959, he became the first president of Ireland to visit the US, when he was the guest of president Dwight D Eisenhower, and he was invited to address both houses of Congress.

He did not refer any bills to the Supreme Court, under Article 26 of the Constitution of Ireland, during his time in office.

A short man, on one visit to a match in Croke Park, he was heckled from the crowd: “Cut the grass, we can’t see the president.”

His drinking remained prodigious throughout his time as president, and Monsignor Pádraig Ó Fiannachta noted that he kept barrels of Guinness on tap in Áras an Uachtaráin.

For all of that, he was a popular president, liked and respected for his decency.

After two terms in the Áras, Seán T O’Kelly was succeeded as president of Ireland, in 1959, by Éamon de Valera. He died on November 23, 1966, at the age of 84.

App?

App?