Cork remembers rebel and leader, Liam Lynch, 100 years on from his death

A century after his death, Fermoy and wider Cork is remembering Liam Lynch, former Chief of Staff of the anti-Treaty IRA.

The dying wish of General Liam Lynch was to be buried in Fermoy beside his comrade Mick Fitzgerald. A century after his death, the town remembers the legacy of the Chief of Staff of the anti-Treaty IRA. Donal O’Keeffe looks back at the life of a legendary Rebel

ON Tuesday, May 2, 1916, a young store worker from Barry’s Timber Yard in Fermoy watched as two men, barefoot, their hands bound, were marched under armed guard across the bridge that would, a century later, bear their name. A horse-drawn cart carrying two wounded men followed behind them.

The barefoot men were William and Thomas Kent of Bawnard House in Castlelyons, and in the cart behind them were their brothers, David and Richard.

They had been arrested after a three-hour siege at their home, in the days after the Easter Rising. A gun battle with the Royal Irish Constabulary had resulted in the death of RIC head constable Rowe.

A week later Thomas would be convicted of the murder of Rowe at a court martial, and executed at Victoria Barracks in Cork. He was 51. David was also sentenced to death but his sentence was later commuted.

William was acquitted, and Richard died of his wounds on May 4. In 2015, 99 years after Thomas Kent’s execution, President Higgins attended the Cork man’s state funeral in Castlelyons.

Watching on in Fermoy as the Kents were paraded through the garrison town in 1916 was 23-year-old William Fanaghan Lynch, born in Anglesboro, Co Limerick, in 1892.

The fifth of seven children born to Mary (nee Kelly) and farmer Jeremiah Lynch, Liam had grown up in a political family. His uncle John Lynch had taken part in the 1867 rising, and his mother was joint secretary of the Ballylanders branch of the Ladies Land League.

In 1910, Liam Lynch took up an apprenticeship at the Mitchelstown hardware shop of P O’Neill (a name which would, half-a-century later, take on coincidental significance in Irish Republicanism).

There, Lynch became a member of the Gaelic League, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and the Irish Volunteers.

In 1914, the Volunteers split over John Redmond’s call that Irish men join the British Army to fight in the Great War. To the disgust of his godmother, Hanna Cleary, Lynch sided with the Redmondites.

A year later, Lynch took up a job with J Barry and Sons in Fermoy.

His time in Fermoy was politically quiet but witnessing the mistreatment of the Kents would change all of that.

Outraged, Lynch became a committed Volunteer and, by early 1917, he was serving as first lieutenant of Fermoy’s small company. By September that year, the Irish Volunteers in East Cork had been reorganised with nine local companies formed into the Fermoy battalion, and Lynch was elected adjutant.

That November, he wrote, in a letter to his brother Tom, a phrase with which he would become forever associated: “We have declared for an Irish Republic, and we will not live under any other law”.

In January 1919, just before the inaugural meeting of the first Dáil and the Soloheadbeg ambush, which would later be seen as the opening salvo of the War of Independence, Lynch became commandant of the newly formed Cork No 2 Brigade, with responsibility for northern Co Cork.

He would become a trusted ally of IRA Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy, and Director of Intelligence, Michael Collins, and they would offer him several promotions to IRA General Headquarters, offers he would consistently turn down. Lynch proved a gifted and inspirational guerrilla leader but his superiors were often appalled at his insistence on leading operations and often placing himself in mortal danger - one example being the 1919 arms raid in Fermoy.

In June of 1920, Lynch led a daring operation which resulted in the kidnapping of the Commander of Fermoy Barracks. Brigadier General Cuthbert Lucas, fishing on the banks of the Blackwater, was captured alongside two colonels, Danford and Tyrell.

The section covering this adventure in Gerard Shannon’s thoughtful and nuanced new Lynch biography, To Declare a Republic – the first in several decades – is worth the price of admission on its own. People from Fermoy will recognise several local, legendary figures, although some may object to the omission of other, allegedly pivotal participants.

Near Rathcormac, captive in the second of two cars traveling on the main road to Cork, Lucas and Danford planned their escape in Arabic, and sprang on Lynch and their driver, Patrick Clancy.

A crash ensued, followed by two fist-fights in the road, which ended with Lynch subduing Lucas, before then shooting Danford. A doctor was sent for, and Tyrell was released to care for the mortally wounded Danford.

Lucas was held in West Limerick and East Clare, where he enjoyed debates with Lynch, card games and whiskey.

After four weeks, he escaped, or perhaps was allowed to escape. Lucas stated he had been treated as “a gentleman by gentlemen”, describing his captors as “delightful people”, a sentiment which cannot have gone down well with his own superiors.

In April 1921, coinciding with his elevation to the IRB Supreme Council, Lynch was made Commandant of the First Southern Division, which covered the three Cork brigades, the three Kerry brigades, the two Waterford brigades, and Limerick West, putting him in command of approximately 31,000 men.

When the Truce with Britain was declared on July 11, 1921, Lynch remained convinced that war would eventually resume, something which clearly informed his later thinking during the Civil War. Vehemently opposed to the Treaty, and the abandonment of the North, Lynch nonetheless strove to avoid a split in the IRA, until the shelling of the Four Courts by the Free State Army steeled his resolve as head of the anti-Treaty IRA.

For nine months, Lynch led a ruinous guerrilla war against the Free State, a war he privately accepted could not be won. By continuing it he hoped to bring the Government “to the position of bankruptcy”, so conflict would be reignited with Britain, and his former allies would be forced “to stand with us in upholding our independence”.

For a gifted tactician, Lynch displayed little skill at strategy, and for a poetic visionary with such a grá for Ireland, he showed absolutely no interest in public opinion or democracy.

Disdaining politics and politicians – in 1920 he had written that the “army has to hew the way to freedom for politics to follow” – he effectively sidelined Éamon de Valera throughout the Civil War.

When Lynch was killed, de Valera mourned his death, but with Lynch had fallen the greatest obstacle to the end of the Civil War. There have been conspiracy theories, as there always are and, as with Collins who died not a year before him, Lynch’s supporters have mapped onto their lost leader the roads not taken, the better Irelands unsullied by negotiation or compromise.

On Tuesday April 10, 1923, Lynch and six comrades were caught on the Knockmealdowns between two columns of the National Army. Struck by rifle-fire and mortally wounded, Lynch ordered his companions, including Frank Aiken who would soon succeed him as Chief of Staff, to leave him behind.

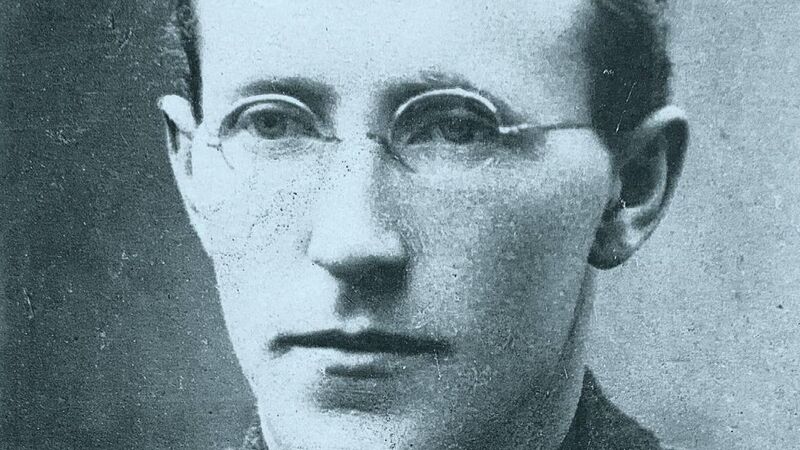

The National Army soldiers initially thought the tall, sallow-skinned, bespectacled man they had captured was de Valera but Lynch informed them: “I am Liam Lynch, Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army. Get me a priest and doctor. I’m dying.”

The soldiers bore Lynch down the mountain on an improvised stretcher to Nugent’s Pub in Newcastle. From there, he was taken by ambulance to the military hospital in Clonmel, where he died just before 9pm.

His last wish was that he be buried in the Republican plot in Kilcrumper in Fermoy, beside Mick Fitzgerald, “the greatest friend I ever had on this earth”.

Twenty days after Lynch’s death, Frank Aiken gave the order to the anti-Treaty IRA to cease military operations, ending the Civil War but copper-fastening partition for a century or more.

App?

App?