Revisiting the Bandon Valley Massacre

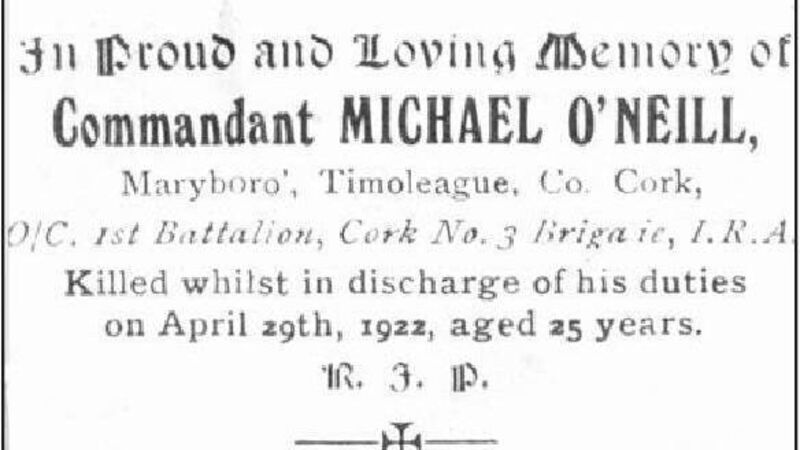

Mass Card for Acting Commadant Michael O’Neill, of the Bandon Battalion of the Cork No. 3 Brigade, at Ballygroman House near Killumney in the early hours of 26 April 1922

A new television documentary revisits a dark chapter in Cork’s revolutionary history, one which remains bitterly controversial a century later.

Over three nights in April 1922, 13 Protestant men and boys were shot dead in West Cork, and a hundred years later their deaths remain a subject of great contention and division.

The Bandon River Valley had at the time the highest concentration of Protestants in southern Ireland, and it was also the cockpit of IRA activity against the British.

It is generally agreed that the sequence of events which led to the spate of murders began with the killing of IRA acting commandant Michael O’Neill in the early hours of April 26 1922.

O’Neill, 25, from Maryborough, Timoleague, with three other men on “special duty”, entered the home of former magistrate Thomas Hornibrook at Ballygroman, near Ovens, with the intention of seizing a motorcar.

Entering the house by a window, O’Neill was shot dead by former British Army captain Herbert Woods, who was related to the Hornibrook family.

The Cork Examiner reported: “It appears that the deceased, accompanied by some other officers, called at the house of a farmer on some official duty. While the officers were standing in the hallway a shot rang out without any warning whatsoever, and the deceased fell dead.” Finding that O’Neill had been “brutally murdered … while in the execution of his duty as an officer of the IRA”, an inquest jury in Bandon later ruled that “the fatal shot was fired by a man named Woods in company with two Hornibrooks, Thos. and Samuel”.

It is believed that Herbert Woods, Thomas Hornibrook and his son Samuel, were executed by the IRA and their bodies were buried in Farranthomas Bog, near Newscestown.

Over the next three days, a further 10 Protestant men and boys were killed in Dunmanway, Ballineen, Castletown Kinneigh, Clonakilty and Enniskeane, in a series of murders which would become known as “the Bandon Valley Massacre” or “the Dunmanway killings”.

While the motive for the murders of Woods and the Hornibrooks seems to have been straightforward revenge for the killing of Michael O’Neill, the subsequent killings appear to have had murkier motivations, with some historians claiming the men were targeted as alleged informants, while others believe they were killed for nakedly sectarian reasons.

Those complexities were acknowledged even at the time, and the killings were widely condemned.

A Dáil statement issued by the Cabinet on April 28 stated that “certain elements in the community are taking advantage of the present transitional period in Ireland to wreak private vengeance in the hope that owing to the unsettled conditions they may escape punishment”.

That same day, IRA commandant Tom Hales threatened capital punishment “if found necessary” for “any soldier in the area” who failed to comply with the order that they were “neither to interfere with or insult any person”.

Michael Collins, chairman of the provisional government, pleaded with “every section of Irishmen” to help bring the killers to justice and to protect “their fellow citizens who may be in danger of a similar fate”.

The president of the Dáil Cabinet, Arthur Griffith, offered the relatives of the murdered men the “profound sympathy of the Irish Nation”.

On April 30, the Catholic Bishop of Cork, Dr Daniel Coholan, condemned what he saw as murders clearly sectarian in motive: “Our country, north and south, is being disgraced before the world. When will it all end? And where shall we end ourselves if, in the north, Protestants continue murdering members of the Catholic minority, and in the south, Catholics take reprisals on the Protestant minority?” Despite the widespread condemnation at the time, public memory of the killings faded with the passing years, until 75 years later a brilliant but controversial Canadian historian put the murders back in the spotlight.

According to Peter Hart’s 1998 book, The IRA and its Enemies, the 13 men and boys were shot because they were Protestants, murdered in a series of sectarian killings carried out by members of the anti-Treaty IRA.

Hart concluded that the gunmen “did not seek merely to punish Protestants but to drive them out altogether”, because, he claimed, “the nationalist revolution had also been a sectarian one”.

Hart’s book was criticised by some historians, not least for his claim that Tom Barry had invented the “false surrender” narrative around the Kilmichael ambush, alleging that Barry had instead ordered the execution of Auxiliary prisoners. Several flaws in the evidence quoted by Hart have been highlighted, especially around his claim to have interviewed survivors of the ambush.

Others have questioned Hart’s claim that those murdered in the Dunmanway killings “were shot because they were Protestant”, pointing to evidence suggesting that they were targeted due to allegations they were informers.

Historian Fr Brian Murphy drew attention to Hart’s citing a British intelligence assessment that “in the south the Protestants and those who supported the Government rarely gave much information because, except by chance, they had not got it to give.” Murphy noted that Hart had omitted the following sentence: “An exception to this rule was in the Bandon area where there were many Protestant farmers who gave information”.

Hart, who died of a brain haemorrhage in 2010, always denied he was a revisionist, but his 1998 conclusions sparked a history war which continues unabated almost a quarter of a century later, with historians, commentators, and politicians taking sides, with claim and counterclaim and allegations of war crimes and sectarian killings against the IRA in West Cork during and after the War of Independence.

Now, a TG4 documentary, Marú in Iarthar Chorcaí (Murder in West Cork), revisits the debate and asks wider questions about the fundamental nature of the Irish revolution itself.

Was it simply a war of liberation from the British empire, or was it, as Hart claimed, also a sectarian war, “a final reckoning of the ancient conflict between settlers and natives”, a war to drive out the British by force along with the Irish Protestant minority?

The documentary’s producer and presenter, Jerry O’Callaghan, grew up at the epicentre of the West Cork killings.

His father, Denis O’Callaghan,was an active member of Tom Barry’s West Cork flying column and a member of the anti-Treaty IRA’s police force set up during the Truce to protect the local Protestant population at a time of lawless uncertainty.

The TG4 documentary includes excerpts from a last long interview Peter Hart did a few months before his death, intercut with recorded debates in the history war he sparked over the Dunmanway killings.

Marú in Iarthar Chorcaí (Murder in West Cork) airs on TG4 at 9.30pm on Wednesday 7 December.

App?

App?