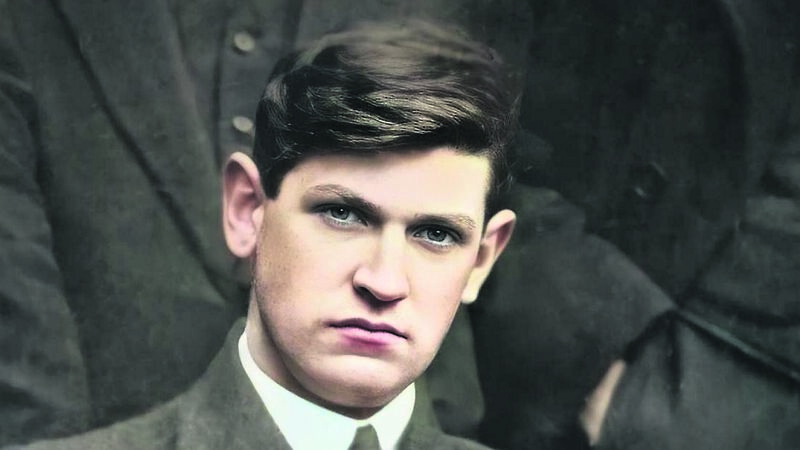

The last moments of Michael Collins: How Cork learned of his fate

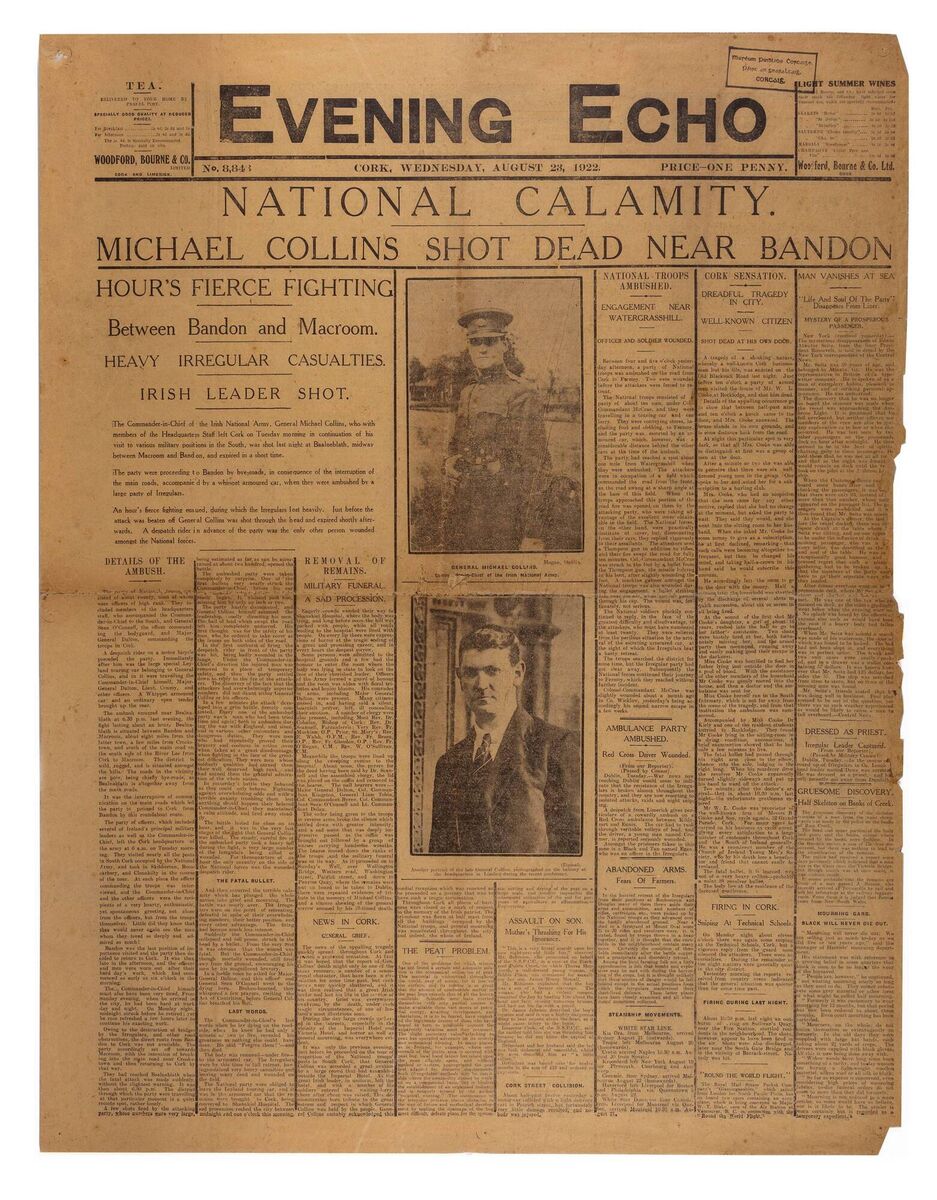

“The grief-stricken populace learned the facts of the calamity in a special early edition of The Evening Echo."

Between 7.30pm and 8pm on the evening of Tuesday, August 22, 1922, just before sunset, a convoy of Free State vehicles was ambushed by a small party of anti-Treaty IRA Irregulars at Béal na Bláth, Co Cork, and General Michael Collins was shot in the head and killed.

The vehicle bearing Michael Collins’s body to Shanakiel Hospital reached the city after midnight, by which time The Cork Examiner had already gone to press.

After what must have been a fraught night in the Academy Street offices shared by the Examiner and the Evening Echo, offices visited by Collins only two days earlier, The Echo was published early on Wednesday, and it was there that most Cork people learned the news.

Most of August 1922 is missing from the Evening Echo archive, but a copy of that Wednesday edition survives in Dalton’s pub in Kinsale, and the front page is also on display in Cork Public Museum in Fitzgerald Park.

“NATIONAL CALAMITY” reads The Echo’s banner headline, above “MICHAEL COLLINS SHOT DEAD NEAR BANDON”.

The headlines continue: “HOUR’S FIERCE FIGHTING Between Bandon and Macroom. HEAVY IRREGULAR CASUALTIES. IRISH LEADER SHOT.”

The article beneath begins: “The Commander-In-Chief of the Irish National Army, General Michael Collins, who with members of the Headquarters Staff left Cork on Tuesday morning in continuation of his visit to various military positions in the South, was shot last night at Bealneblath [sic], midway between Macroom and Bandon, and expired in a short time.

“The party was proceeding to Bandon by bye-roads, in consequence of the interruption of the main roads, accompanied by a whippet armoured car, when they were ambushed by a large party of Irregulars.

“An hour’s fierce fighting ensued, during which the Irregulars lost heavily. Just before the attack was beaten off General Collins was shot through the head and expired shortly afterwards. A despatch rider in advance of the party was the only other person wounded amongst the National forces.

“The party of National troops consisted of about twenty, most of whom were officers of high rank.

“They included members of the headquarters staff, who accompanied the Commander-in-Chief to the South, and General Sean O’Connell, the officer commanding the bodyguard, and Major-General Dalton, commanding the troops in Cork.

“A despatch rider on a motor bicycle preceded the party. Immediately after him was the large special Leyland touring car belonging to General Collins, and in it were travelling the Commander-in-Chief himself, Major-General Dalton, Lieut. Conroy, and other officers. A Whippet armoured car and an ordinary open tender brought up the rear.

“The ambush occurred near Bealnablath [sic] at 6.30pm last evening, the fight lasting about an hour. Bealnablath is situated between Bandon and Macroom, about eight miles from the latter town, a few miles from Crookstown, and south of the main road on the south side of the River Lee from Cork to Macroom. The district is wild, rugged, and situated amongst the hills.

“The roads in the vicinity are poor, being chiefly bye-roads, as Bealnablath is altogether away from the main roads.

“It was the interruption of communication on the main roads which led the party to proceed to Cork from Bandon by this roundabout route.

“The party of officers, which included several of Ireland’s principal military leaders as well as the Commander-in-Chief, left the Cork headquarters of the army at 6am on Tuesday morning.

“They visited all the posts in South Cork occupied by the National Army, and … at each place the officer commanding the troops was interviewed, and the Commander-in-Chief and the other officers were the recipients of a very hearty, enthusiastic, yet spontaneous greeting … from the troops themselves.

“Little did they know that they would never again see the man whom they loved so deeply and admired so much!

“Bandon was the last position of importance visited and the party then decided to return to Cork. It was then late in the afternoon, and the officers and men were worn out after their hard day’s work, which had commenced as early as six o’clock in the morning.

“The Commander-in-Chief himself must also have been very tired. From Sunday evening, when he arrived in the city, he had been hard at work day and night. On Monday night, midnight struck before he retired; yet he rose refreshed a few hours later to continue his exacting work.

“Owing to the destruction of bridges by the Irregulars, and other road obstructions, the direct route from Bandon to Cork was not available. The party accordingly set off towards Macroom, with the intention of breaking into the main road near Crookstown and then returning to Cork by that way.

“They had reached Bealnablath when the fatal attack was made suddenly, without the slightest warning. It was then about 6.30pm. The district through which the party were travelling at that particular moment is a quiet, remote spot, rather lonely.

“A few shots were fired by the attacking party, whose numbers were very large, being estimated as can be ascertained at about two hundred, opened fire.

“The ambushed party were taken completely by surprise. One of the first bullets very nearly struck the Commander-in-Chief before his car was stopped, indeed before the fight really began. It whizzed past him by only an inch or two.

“The party hastily dismounted, and General Collins himself assumed the leadership, coolly directing his men. The hail of lead which swept the road left him completely unmoved.

“His first thought was the safety of his men, who he ordered to take cover at the fences on both sides of the road …

“The discovery of the fact that the attackers had overwhelmingly superior numbers did not daunt either General Collins or his officers.

“In a few minutes the attack developed into a grim battle, fiercely contested. … The battle lasted for close on an hour, and it was in the very last stages of the fight that General Collins was killed.

“The steady, careful fire of the ambushed party took a heavy toll during the fight, a very large number of the Irregulars being killed or wounded …

“And then occurred the terrible calamity which has plunged the whole nation into grief and mourning ... Suddenly the Commander- in-Chief collapsed and fell prone, struck in the head by a bullet.

“From the very first it was obvious that the wound was fatal. But the Commander-in-Chief, though mortally wounded, still fired away from the ground, encouraging his men by his magnificent bravery.

“In a feeble voice he asked for Major-General Dalton, and this officer and General Sean O’Connell went to the dying hero. Broken-hearted, they whispered a few prayers, reciting the Act of Contrition, before General Collins breathed his last.

“The Commander-in-Chief’s last words when he lay dying on the roadside, when he knew he had only a minute or two to live, revealed his greatness as nothing else could have done. He said ‘Forgive them!’ and then died.

“The body was removed, under fire, to the armoured car. The Irregulars were by this time in full retreat, having sustained very heavy casualties and leaving many dead and wounded on the field.

“The National party were obliged to leave the Leyland touring car, and it was in the armoured car that the remains were brought to Cork, being conveyed to Shanakiel Hospital. The sad procession reached the city between midnight and one o’clock this morning.”

Final journey back to Cork and on to Dublin

In fact, the armoured car had to be abandoned, bogged down in a field near Killumney, and the remains were brought to the city on the Crossley Tender.

The Evening Echo edition on display in Cork Public Museum carries a piece entitled “REMOVAL OF REMAINS”, reporting the journey, around noon that Wednesday, of Collins’s remains from Shanakiel to Sundays Well, to the Western Road and into the city, and finally to Penrose Quay and onto the Classic, the ship which would bear him to Dublin.

The next morning, much of The Cork Examiner’s coverage recycled The Evening Echo’s reporting, noting that on hearing the news “Cork was at once plunged into mourning. All the business establishments ceased work for the day, and all the trams stopped running.

“The grief-stricken populace learned the facts of the calamity in a special early edition of The Evening Echo.

“At noon yesterday the body was accorded a military funeral from the Hospital to Penrose Quay .

“Crowds who thronged the streets openly displayed their grief at the loss of a gallant Corkman and an Irish National Hero.”

Thursday’s Evening Echo took up the story as Collins’s remains arrived in Dublin in the early hours of the morning:

“Huge crowds assembled at North Wall Quay at midnight to await the arrival of the SS Classic...

“Members of the Government, including Mr Cosgrave, Acting President, Dáil Éireann, were present in addition to National Army Commanders.

“Attached to the gun carriage was an 18-pounder gun upon which had been constructed a wooden platform to carry the coffin. Beside the gun stood General Collins’s chestnut charger, saddled and led by a soldier groom.

“At two o’clock the Classic berthed silently. Scenes, typical of the nation’s sorrow, marked the progress of the coffin through the long avenue of troops.

“The plain oak casket was draped in Free State colours, and the procession poured into the streets to the mortuary at St Vincent’s Hospital, the coffin being on the platform of the gun.

“By its side walked the General’s charger, the Ministers of the Provisional Government, Deputies of Dáil and members of Headquarters Staff of the National Army followed, and after came bareheaded men and women, many in tears.

“The silence of the night was broken only by the distant crack of the sniper’s rifle. The cortege was flanked by Dublin Guards, and in the rear marched a detachment of the new Civic Guard …

“Several of those of the ambushed party accompanied the body on its journey, among them was a boyish figure wearing a ragged civilian coat and a tweed cap with a Lewis gun slung across his shoulders.

“He said that when his ambushers opened fire the driver of General Collins’s car wanted to drive on at full speed but the General ordered him to stop, ordered the troops to take cover and took command of the whole situation. There were at least 250 against twelve of them!

When hit, the General, though bleeding, continued firing.”

This ties back to our reporting of the ambush where, absent of any reporters at the scene, the newspaper was reliant on information provided by the Provisional Government.

It is generally accepted now that most of the ambush party at Béal na Bláth had dispersed by the time Collins’s party returned there, with perhaps only five or six men there to open fire on their former general.

Likewise, the claim of a “very large number of the Irregulars being killed or wounded” was incorrect, and Collins was the only fatality.

In his 2021 book Between Two Hells: The Irish Civil War’, historian Diarmaid Ferriter is critical of the National Army’s “myth-making” around Collins’s death, especially the claim that his last words were “forgive them”.

Ferriter also suggests his last words were “much more likely” to have been “the more prosaic ‘Emmet, I’m hit’, these words being addressed to Emmet Dalton, in whose lap he died a few minutes later”.

App?

App?