Cork Fenian Brian Dillon had a lion’s heart in a small, sickly body

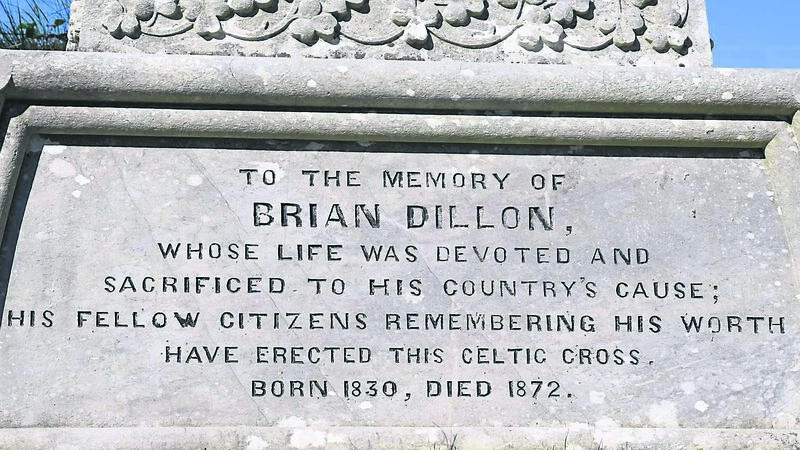

The inscription at the grave of Brian Dillon at Rathcooney Graveyard, Cork. Picture Denis Minihane.

THOUGH rooted in Kilkenny, which was the birthplace of two of the founders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, James Stephens and Michael Doheny, Cork was the capital of Fenianism. In the 1860s, IRB membership in Cork vastly surpassed that of other counties and when Stephens embarked on his 3,000km walk of the country in 1856, to gauge the mood of the people and the appetite for insurrection, he drew considerable support around Cork City and West Cork.

It was on this nationwide tour that Stephens came into contact with Brian Dillon, through the acquaintanceship of a shoe manufacturer, John Mountaine. Mountaine became the first Corkman to take the IRB oath. Dillon soon followed.

Dillon grew up in a small house on the road leading from Ballyvolane Cross to Rathcooney, in 1830, to parents Edward Dillon and Margaret Dill. At an early age, Dillon moved with his family to a house at Barrackton Cross, at the junction of Old Youghal Road and Ballyhooley Road.

There, his parents opened a tavern and the junction became known colloquially as Dillon’s Cross. At the age of 20, Dillon joined WR Coppinger’s solicitors on 57 South Mall in Cork City, as a writing clerk, tasked with finalising deeds and documents for filing in court. In 1863, Dillon’s father, Edward, died, after which he left his job at Coppinger’s to take over the tavern at Barrackton (Dillon’s) Cross. It is at this point that Dillon’s role in the Fenian movement took hold.

The Fenian movement was clandestine. They secretly drilled and secured arms and waited patiently, and ofttimes frustratingly, for Stephens to give the go-ahead for revolt. While little is known of Dillon’s involvement, letters sent from O’Donovan Rossa indicate that he was authoritative in the organisation as early as 1860 and it is believed that Dillon was colonel in Cork.

Geary’s public-house on North Main St, a blacksmith’s forge off Bishop St, and the premises of the Cooper’s Society on Dominick St were the principal meeting places for covert discussion and lectures on engineering and military training.

DILLON'S CIRCLE

Meanwhile, ‘Fair Field’ and ‘the Tawnies’ (near Rathpeacon) acted as the staging grounds for Dillon’s circle, and it’s there they practised manoeuvres and exercises in preparation for rebellion.

Late in 1864, however, John Warner, a native of Bandon, was accepted into the Fenian ranks in Cork. Warner had previously served as a British soldier during the Crimean War, before he ‘became a Catholic’. Despite his background (or perhaps, because of it: Few Fenians would have had military experience), Warner was welcomed into Dillon’s circle and became a key figure in co-ordinating drilling. The naivete of the Cork Fenians in enlisting such a figure would soon prove costly.

Warner informed a magistrate that the IRB in Cork were plotting to attack a barracks, seize the weapons, and kill the Catholic Bishop of Cork, who had opposed Fenianism. Geary’s pub was given as the headquarters for sedition. And on the evening of September 15, 1865, the fateful blow fell. The raids started around midnight and Dillon was one of the first to be arrested, dragged from his home at Dillon’s Cross. Some drawings, incriminating letters, and a pair of field glasses were found sewn into the mattress of his bed. John Lynch, another central figure in Cork, was arrested on Devonshire St.

The following day, Dillon and Lynch were placed together in the dock at Cork courthouse, to be defended by the renowned Isaac Butt. The official indictment was one of treason felony and of ‘having entered into a conspiracy to depose the queen and establish a republic in Ireland’.

The traitor Warner identified the two men as being present at drill meetings in Gearys’ pub, but while one newspaper commented that his character ‘is such that testimony should not warrant the hanging of a cat’, seditious documents, such as letters written from Dillon to Stephens and Thomas Clarke Luby, were to be his undoing.

At this juncture, Dillon could not have constituted a military threat. Having experienced a ‘heavy fall’ as a child, Dillon suffered from a ‘curvature of the spine and general ill-health’. He likely had scoliosis or kyphosis, as a result of ineffectively treated vertebral fractures. The hunchbacked Dillon grew to a mere 4ft 9¾ (from Cork Prison records, December 16, 1865). The following extract from The Nation newspaper, dated December 23, 1865, offers a vivid description of ‘little Dillon’:

“Dillon, alleged to be ‘Head Centre’ for Cork City and the fidus achates [devoted follower] of the head conspirator, is surely, of all the members of the organisation, apparently the most ill-suited for the position. It may be, however, that nature has compensated for bodily imperfections by keenness of intellectual and mental vigour. Dillon is about four feet nine inches in height. His face is disproportionately large, his eyes sunken and piercing, the cheek bones large and high, and the chin of sharp outline.”

VERDICT

It took less than 20 minutes for the jury to bring a verdict of ‘guilty’ against the two men. Both men made short statements, Dillon protesting that “with respect to the observations of the attorney general, which pained me very much, that it was intended to seize property, it does not follow, because of my social station, that I intended to seize the property of others…my belief in the ultimate independence of Ireland is as fixed as my religious beliefs “.

At this point, he was stopped by Judge Keogh, who said he would not listen to such sentiments and continued, “You, Brian Dillon, have been, from an early period, the tried and confidential adherent of Stephens and Luby…we cannot arrive at any other conclusion but that you must be kept in penal servitude for 10 years”. With that, Dillon and Lynch were hustled down the steps from the dock to the cells underneath.

Dillon was brought by train from Cork to Dublin, where was kept in Mountjoy. On arrival, he was stripped naked, searched, and put into convict clothing. He spent nearly half a month there, until in January 1866, he was transferred, via boat and train, to Pentonville in north London.

Dillon’s chest and throat were giving him trouble, because of the curvature of his spine. Sleeping proved almost impossible on the wooden board that acted as his bed. Within a month of incarceration at Pentonville, his left leg became paralysed and by May, Dillon, now seriously ill, was transferred to Woking Invalid Prison in Surrey. This would be his home for the next four and a half years.

In August 1868, Cork Corporation became the first civic body to plead for a general pardon for Fenian prisoners. In debates, the councillors maintained that the incarceration of men like Dillon was “a disgrace to England”, given their “unselfishness, amazing self-sacrifice and…patriotism”. Most Irish people believed that “the political prisoners have suffered sufficiently to vindicate the power of British law”, which was contrary to “the practice of all civilised countries in relation to political offenders”.

The widespread interest in the prisoners resulted in the formation of a central amnesty committee, and Isaac Butt, Dillon’s defender in ’65, soon became president of the new movement. While invalided at Woking, Dillon worked long hours of prison labour. One of his jobs involved hoisting heavy bricks from the ground to a scaffold overhead, even though he had dysentery.

ILLNESS

A falling brick hit Dillon and rendered him unconscious, after which he spent many weeks in hospital.

For the remainder of his time in Woking, he lived in severe pain, suffering from shingles, neuralgia, rheumatism, and an ever-spreading paralysis.

The pressure imposed on British governance by the committee resulted in the Devon Commission, an inquiry tasked with ascertaining whether the health of Fenian prisoners had been treated with “unnecessary severity or harshness” or “subjected to any exceptional treatment in any way”.

The Devon report concluded that the Fenians had grounds for complaint concerning diet, medical conditions, and disciplinary actions undertaken by prison administration, which “exceeded the power and authority entrusted in them”.

As a result, the British government ordered that the incarcerated Fenians be exiled until their prison sentences elapsed. However, Dillon rejected this ‘Sham Amnesty’ until eventually, in January 1871, on account of the state of his health and inability to cross the Atlantic to America like the rest of the Fenian prisoners, the government acquiesced.

FREEDOM

On February 8, 1871, Brian Dillon was set free. His torturous ordeal was over.

On February 13, Brian Dillon travelled home by train. Large crowds gathered to cheer his return on the platforms at Kildare, Templemore, Limerick Junction, Kilmallock, Charleville, Mallow, and Blarney.

The train reached Cork at 8:10pm that night, to be met by a buoyant and restless crowd that occupied every inch of the station on the Lower Glanmire Road. From there, Dillon made the short and triumphant journey to his home at Dillons Cross.

The following extract from the Cork Examiner details Dillon’s homecoming.

“As the car drove along, the crowds that lined King Street on both sides made the air resound with their cheers and cries of welcome, while city bands played national airs alternately.

“The bands were succeeded by blazing tar-barrels and torches, until they arrived at Scots Church, where they turned up the St Luke’s Road.

“The hills on the way were studded with lighted tar-barrels and the houses in the neighbourhood of Ashburton were all illuminated. The crowds were increasing every moment and by the time Mr Dillon’s house was reached, the whole space opposite the front was a mass of human faces. The enthusiasm of the people knew no bounds and cheer after cheer rang forth in honest welcome.”

But once the celebrations had subsided, Dillon’s grave ill-health soon became apparent. His aging mother, along with relatives and friends, tried to nurse him back to health, while donations came from the Fenians in America to aid his recovery.

By the summer of 1872, with Dillon’s left side mostly paralysed, tuberculosis began to take hold. On Saturday, August 17, 1872, Brian Dillon died at his home in Dillon’s Cross.

As the sad news of Dillon’s passing began to reverberate around the city, funeral plans were immediately put in place. It was decided that a vault would be built at the family burial-ground in Rathcooney, not far from where Dillon was born.

To allow time for its construction, Dillon’s body was temporarily laid at St Joseph’s Cemetery, Turner’s Cross, where it remained for six days.

FINAL JOURNEY

The funeral took place on Sunday, August 25. Thousands of people, including trainloads from Limerick and Tipperary, flocked to St Joseph’s Cemetery, as the procession made its way from Evergreen St, through Anglesea St, the South Mall, Grand Parade, King Street, and St Luke’s. Prayers were then recited for the repose at Dillon’s Cross outside Dillon’s home, before the procession moved through Ballyvolane and up the steep hill towards the graveyard.

Col Rickard Burke, a native of Dunmanway and a former member of the Fenian Brotherhood in America, delivered the funeral oration.

“As an Irishman swayed by the broadest and most generous principles, the prominent part he took in the Irish Republican Brotherhood is already widely known…with him, reflection was decision, and decision action; and throwing himself into the ranks of the popular cause with the zeal and earnestness of his nature, we find him in ’59 and ’60 working with a fixity of resolution that justly won the esteem of the national party and soon became the guiding spirit of the south of Ireland…Placing the remians of our dear friend here in a tomb built of stones from the very house where he drew his first breath, we may confidently leave him to the esteem of his friends, to the gratitude of his country, and to the mercy of his God.”

And with that, the mortal remains of Brian Dillon were laid to rest.

- Brian Dillons GAA Club will be marking the death of Brian Dillon with a wreath-laying ceremony at Dillon’s resting place in Rathcooney Cemetery on August 21 at 11am, at which Taoiseach Micheál Martin and Tánaiste Leo Vardakar will be speaking. Ger Canning will be the MC.

In Mountjoy... Dillon was stripped naked, searched, and put into convict clothing. He spent half a month there. In January 1866, he was transferred, via boat and train, to Pentonville in London

App?

App?