Cork's ‘Fireman’s Rest’ is restored to former glory... here's the history behind it

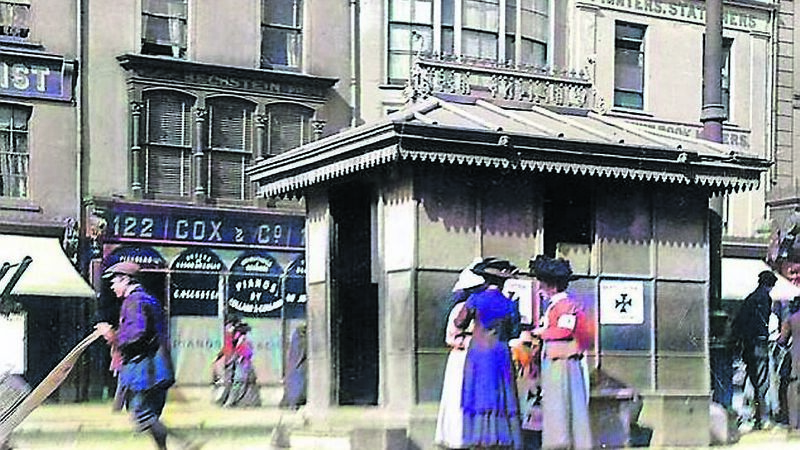

The ‘Fireman’s Rest’ in 1910. The ladies are collecting for ‘Hospital Saturday’, a local charity. The levers of the wheeled escape may be seen at left of picture.

IN 1877, when Dublin fire officer Mark Wickham arrived in Cork to command its newly-established Fire Brigade, he was shocked at what he found and set about changing hearts and minds.

For the first time in Cork, he insisted, the preservation of human life must take precedence over the saving of property during fires.

The Cork brigade was - literally - a one-horse outfit. Their ‘appliance’ - little more than a pony and trap - was incapable of carrying a heavy rescue ladder to a fire, and any attempt at rescuing people from the upper storeys of a building required long ladders to be rushed, manually, through the streets.

The idea of mounting ladders on large wheels was mooted. Thus, the ‘wheeled escape’ arrived. Usually made in three telescopic sections, the larger models could reach to a height of 60ft (about 20 metres) and were extended by turning a windlass.

Initially, Cork’s wheeled escape was kept in the yard of the fire station on Sullivan’s Quay, from where it would be trundled laboriously through the streets to fires. If, for example, the escape was required at the top of St Patrick’s Hill, one can imagine the time that took.

Passers-by who helped to wheel it were given a token by the fireman-in-charge, which could be exchanged for a few shillings at City Hall.

In 1891, Wickham was superseded as fire chief by Alfred J. Hutson, a Londoner.

By now, the city was expanding and his goal was to have an escape in each city ward.

In time, escapes were stationed in Sullivan’s Quay, Grand Parade, St Luke’s Cross, Roman Street, Lavitt’s Quay, Sunday’s Well, Washington Street, Shandon Street, Henry Street, Rocksavage, Grattan Street, Blackpool, and Patrick Street.

On receiving a fire call, a section would turn-out from Sullivan’s Quay, drop a man at the nearest escape to the address, and carry on to the scene. The lone firefighter would hastily recruit helpers (preferably policemen, as they wouldn’t have to be paid) and all would push the appliance to the fireground.

Many Corkonians owed their lives to the escapes and the firefighters who used them for decades.

When the first escape-carrying fire engine was acquired in 1930, all the street escapes were withdrawn. Now, the rescue ladder could reach any part of the city in minutes of the alarm being raised.

However, the shelter that had been used by the firemen on duty in Patrick Street was left in situ, and for a short time continued to be used by personnel of the tramway company.

A year later the trams disappeared from the street, and the shelter was the sole domain of the city bus staff.

A genuine piece of Victoriana, it book-marked the northern end of (the largely Victorian) Patrick Street from 1904 until 2002, when it was removed as part of the revamp of the city centre public realm.

Now it is set to be unveiled in all its restored glory near the current fire brigade HQ in Anglesea Street.

For generations of Corkonians, the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ - as it was always known - was as well-known as the Berwick Fountain, Mangan’s Clock, or the National Monument.

However, almost from day one, it was never far from controversy, and it was detested by the firefighters.

******

After a bad fire, it was decided the escape positioned in the city centre should be manned by night, and the City Engineer was tasked with designing a suitable shelter of a ‘light and ornate character’ at a cost not exceeding £60.

The shelter, with ‘Fireman’s Rest’ emblazoned along its roof on a wrought-iron scroll, was made by the famous Saracen ironworks of Walter MacFarlane and Co, Glasgow.

It became operational on Monday, May 9, 1892. Uniquely, it had direct phone links both to the fire station and the chief’s residence; one of the relatively few functioning phones in Cork at that time.

The responsibilities of the duty firefighter were clearly detailed in Brigade Orders, including a stipulation that he must never close the door, regardless of the weather:

“While on duty, the fireman is on no account to leave his station. The watch-box is provided as a protection against inclement weather and must not be used by any other person. The door must not be closed when the fireman is within, as he is expected to be vigilantly zealous for the preservation of life and ready to give immediate attendance whenever required.”

For a while, the ‘Rest’ was located at the junction of Grand Parade and Great George’s Street (now Washington Street). But, in April, 1893, a Director of Alexander Grant’s department store, complained it was obstructing the view of their handsome new shop front on the Grand Parade (now the site of the Capitol complex). Capt. Hutson and the City Engineer visited agreed to shift it 20ft to the south - if Grant’s paid the cost.

However, local residents said they were quite happy with the position of the ‘Rest’, thank you very much, and objected vociferously to any suggestion of its relocation - even by 20ft.

For 12 months, the debate batted to and fro, until, in March 1894, the City Fathers, with reluctance, agreed the shelter would be moved to Lavitt’s Quay, opposite the Opera House.

******

The Cork electric tramway system came on stream in December, 1898. The ‘hub’ of the service was the Fr Mathew Statue on Patrick Street. A small ticket office was positioned on the southern side of the statue.

After a fatal fire at Alcock’s shop (near SS Peter and Paul’s church) in November, 1900, the company was approached by the brigade with a view to allowing the duty fireman (from Lavitt’s Quay) the use of the ticket office from 11pm to 7am. The escape would be wheeled into place at the statue for the night. In the morning, it would revert to its station at the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ on Lavitt’s Quay.

Permission was duly granted and a firefighter began night-duty at the ticket office in February, 1901.

Three years later - again with the company’s agreement - the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ and escape were moved from Lavitt’s Quay to Patrick Street where the ‘Rest’ permanently supplanted the small ticket office.

Electric lighting and a telephone were installed, and, from then, barring a period during the ‘Troubles’ (when the city centre escapes were relocated to Conway’s Yard on Oliver Plunkett Street and the yard of the Imperial Hotel on Pembroke Street) until 1930, the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ was used by the tramway personnel by day and the Fire Brigade by night.

In February, 1894, Capt. Hutson reported to the service journal Fire and Water thus: “We have a central street station [the ‘Fireman’s Rest’] now with fire escape, hose, standpipes and other gear. It is very nicely fitted inside and out; in fact, I think it is one of the most comfortable outstations in the Kingdom. There is a good water service with plenty of hydrants in the city, but in some instances the mains have been laid too great a distance for their size.

“The men are all thoroughly equipped, and I can muster, with the paid, auxiliary and volunteer staff, close upon 30 men in a few minutes. A night turn-out takes about 2½ minutes with men fully dressed and horses out.”

Hutson may have considered the ‘Rest’ comfortable, but it was the most unpopular duty with the firefighters. Generally, a man did night-duty each month; but Fireman Timothy Ahern, requesting a change of roster, claimed he had been on night-duty at the ‘Rest’ without a break for a period of a year and eight months.

The ‘Fireman’s Rest’ was, without doubt, he said, ‘the worst station in the city’.

The men complained the unheated shelter was injurious to their health and the iron walls ‘sweated’ due to the condensation of vapour. Also, due to the order stating the door be left open regardless of weather, they often came off their tour of night-duty half-frozen.

The saddest chapter in the life of the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ was on the night of Wednesday, November 17, 1897. Fireman James Barry arrived at the ‘Rest’ on Lavitt’s Quay to relieve duty officer, Mark Wickham. On entering the shelter, he found him lying on the floor in a collapsed state. He was immediately removed to his residence at Sullivan’s Quay but, sadly, never regained consciousness.

The ‘late and first Captain of Cork Fire Brigade’ was 59 and had served in Cork for just over 20 years.

App?

App?