A drisheen recipe that Joyce recommended!

Tripe and drisheen in Cork’s English Market

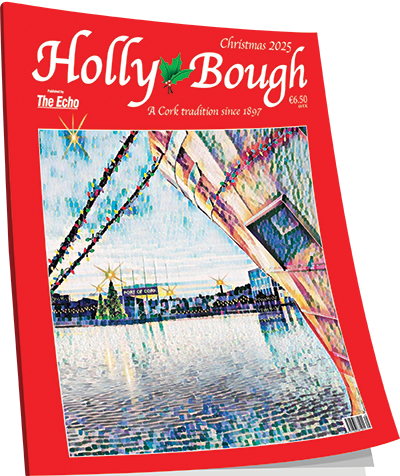

THINK of James Joyce, think of Ulysses; think of Dublin, too, maybe.

But for all the fame of Ulysses, a story about a day in the life of a city (Dublin), Joyce was a Corkman. He alluded his readers to that fact using food as a literary tool, and no food is more Cork than drisheen.

Dr Flicka Small is an expert in the use of food in Joyce’s writings.

The author regularly used locations - street names, buildings, towns and villages - as a way to show off his knowledge not just of the city, but the county.

In A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man, for example, he visits the Victoria Hotel on Patrick Street.

“Joyce’s father was born in Anglesey Street, baptised in St Finbarr’s, and was married in St Peter and Paul’s church just off Paul Street. Ellen O’Connor, Joyce’s grandmother, is buried in Nano Nagle Place,” explains Flicka.

Joyce was born in Dublin, but his father John Stanislaus Joyce, was born in Cork and lived there until he was about 20 years old. In his whole life, James spent just one week in Cork, but through his strong bond with his father, listening to stories of Cork, places and people permeated his mind.

“All the bad stories in Ulysses, the drinking stories, the swear words, are meant to all be related back to Joyce’s father,” explains Flicka. “So, although James Joyce didn’t live in Cork himself, he lived Cork through his father.”

The close relationship Joyce had with his father stubbornly persisted, even as their family’s situation rapidly reduced to very limited means due to his father’s insatiable appetite for drink.

“His father’s family started off as builders’ merchants and had lime and gravel works everywhere. They owned a massive amount of property in Cork - from Dunbar Street to White Street, up to Douglas Street and down to South Terrace - his father lived on Anglesey Street, and they owned all the property in between,” says Flicka.

“Joyce’s father would have been very comfortable, with a civil service job in Dublin and income from the rents from all that property, but in the end, he drank his way through all of it and ended up very poor.”

Joyce’s early life was one of desperate poverty. In Portrait, Flicka says, “Joyce describes his mother picking lice off his clothes, his sisters in the evening stewing up nothing to make something to eat and drinking out of jam jars. They would move frequently before landlords came to get the rent.”

It was this existence, rife with destitution, that motivated Joyce to leave Ireland in 1904 to settle in Trieste, Italy, and where he began to write A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man. Away from the poverty that plagued his formative years, the drunkenness and violence that came with it, Joyce wrote in a semi-autobiographical way about his life and wrote fondly of Cork.

In total, Joyce spent little over a week in Cork over two separate visits, yet, says Flicka, “people say Joyce spoke with a Cork lilt. He spent a week here in 1894 as a child with his father to sell properties in the South Parish because his father had drunk [all the money] away.

“He came back for barely a day, much later in 1919, after visiting Dublin searching for a suitable premises to open Ireland’s first dedicated cinema on Mary Street, The Volta. He wrote to his brother and said, ‘I’ve just spent five rainy, dreary hours in Cork and I’m coming back!’”

A possible reason that consumption of drisheen has declined over the years is its lingering stigma as a food eaten in times of poverty. Joyce referenced drisheen in Portrait vividly, recalling the visit in 1894 to Cork city with his father to sell off property to continue funding his drinking habit.

“They drove in a jingle across Cork while it was still early morning and Stephen finished his sleep in a bedroom of the Victoria Hotel. […] Mr Dedalus had ordered drisheens for breakfast and during the meal he cross-examined the waiter for local news. […] On the evening of the day on which the property was sold, Stephen followed his father meekly about the city from bar to bar. To the sellers in the market, to the barmen and barmaids to the beggars who importuned him for a lob… They set out early in the morning from Newcombe’s coffeehouse where Mr Dedalus’ cup rattled noisily against the saucer […]”

Joyce’s father has come to Cork to sell property because he is out of money and Joyce’s refence to drisheen could be to emphasise this lack and want. Yet they are eating their drisheens served to them by a waiter in a respectable hotel. It is a contradiction, one that few from outside Cork may have picked up on.

Through those few lines, Joyce brings Cork city to life.

Flicka notes that jingle is an old Cork slang term for a covered carriage, like a taxi. Joyce references the Victoria Hotel, which today remains a well-known Patrick Street landmark. He mentions Newcombe’s coffee house which, Flicka says, was really called Newsom’s, now the site of Permanent TSB and previously Woolworths. He mentions a market, most likely The English Market, from where drisheens would have been sold by the O’Reilly family, and of course, the drisheens themselves.

“‘Mr Dedalus orders drisheens for breakfast’ is a definite thing: it tells us we know he’s in Cork, and we’ve had explicit references to the station, the jingle, the Victoria Hotel, and drisheens.

“But Joyce had probably never seen drisheen. He would have eaten offal and cheap cuts of meat [in Dublin], but not drisheen because it’s very specific to Cork. Joyce is using drisheen as a signpost for Cork,” explains Flicka.

Tiny details like these create a vivid sense of place. Rather than describing the spires of Cork, the river, or grand buildings, Joyce relished things that were ordinary, everyday and everyman. Walking down Patrick Street and eating drisheens for breakfast couldn’t have been more ordinary for the people of Cork.

Portrait was published as a book in 1916. Years later came Finnegan’s Wake in 1939, Joyce’s literary experiment laden with double meanings, use of puns in multiple languages, and uncompromising in its refusal to conform to any kind of acceptable literary standard.

But there is one sentence in Finnegan’s Wake widely accepted as the most lucid, clear and uncomplicated sentence in the book’s entirety, and it concerns drisheen!

“(Correspondents, by the way, will keep on asking me what is the correct garnish to serve drisheens with. Tansy Sauce. Enough.)” [Book 1.6 p 164.21]

The statement is written in brackets, and the text prior to and after it bear little correlation to each other. Given Finnegan’s Wake was heavily and serially edited, adding multiple layers of complexity, could it be that this thought slipped in by the hand of an addled editor?

Whether its inclusion is intentional or not, it is there, and there is much to unpick in it too.

It took Joyce 17 years to write Finnegan’s Wake, during which time he had lived in Paris and Zurich and earned good money from Ulysses, (published in 1922).

“Joyce loved food, and spent a huge amount of money on food,” says Flicka, “taking people out to dinner and enjoying the finer tastes in life.”

This bizarre unattached statement in Finnegan’s Wake about drisheens may tells us Joyce was being regularly asked about it by correspondents (journalists). Maybe his Cork roots and this unusual food of the city was a question that came up frustratingly often when being interviewed?

There were once three types of drisheen: sheep, beef and tansy.

Tansy is a wild, bitter herb once used to flavour drisheen, commonly eaten with a white sauce seasoned with onions. In stating that drisheen should be served with a refined Tansy Sauce as the proper garnish, Joyce elevates the humble drisheen.

Possibly, this speaks to his increasingly sophisticated tastes that came with success and money, while still utilising drisheen to uniquely signpost his Cork heritage and identity.

Joyce’s mentions of drisheen in his writing may not be numerous, but the fact that they are there at all is what makes them so interesting.

The period between writing Portrait and Finnegan’s Wake is significant too; between 1916 and 1939, Ireland was redefining itself as a new nation state - post famine, post-independence and civil war, and bookended by two World Wars.

Identity was not just personal, it was political, too; and drisheen is not just distinctly Irish, but distinctly Cork.

Drisheen and Tansy Sauce

Try this recipe to taste James Joyce’s favourite way to eat drisheen.

Forgotten Skills Of Cooking, by Darina Allen, includes this recipe for Tansy Sauce. Serve the sauce with rounds of drisheen fried in butter, or with bacon for additional flavour.

Tansy Sauce

Ingredients

First make a bechamel sauce (this makes enough for the final sauce)

450ml whole milk

1 small carrot, sliced

1 small onion, sliced

1 sprig thyme

Parsley stalks

25g of roux (melt butter, add flour and cook to a soft paste)

Salt and pepper

Method

Put milk in a saucepan and add everything except roux, salt and pepper.

Bring slowly to the boil and simmer for a few minutes to extract the flavours.

Strain, discard the vegetables and herbs, bring the milk back to the boil, thicken with the roux and season with salt and pepper.

Tansy Sauce

Add 1 tablespoon finely chopped tansy to your bechamel sauce, stir through and heat until just below simmering point.

Serve over just cooked drisheens.

Next week, in the final part of the series, I look at the traditional ways of cooking drisheen and exclusively showcase two new drisheen recipes by two exciting Cork chefs.

App?

App?