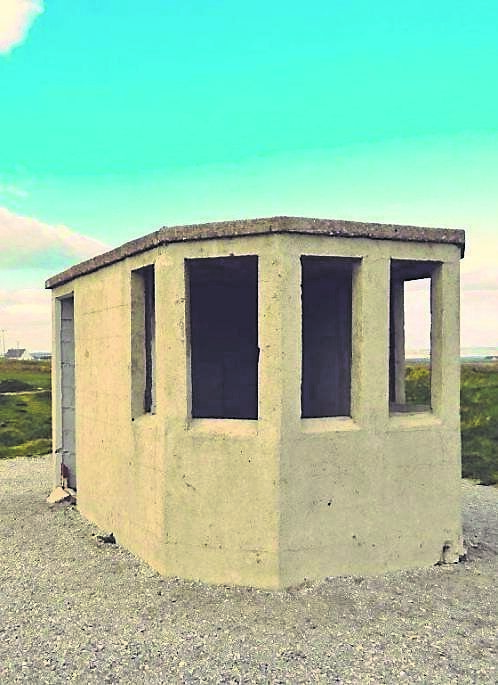

WWII coast teams who kept watch over Cork

A volunteer in Ireland’s Coastwatching Service, affectionately known by the rest of the Defence Forces as the ‘Saygulls’

The Coastwatching Service was established when The Emergency was declared in Ireland on the outbreak of World War II in September, 1939.

By war’s end there were 88 LOPs placed at strategic points along the Irish coastline, positioned, on average, every five to ten miles apart.

The occupants of many lifeboats, grievously wounded and in terrible distress, the survivors of attacks on convoys and sea battles, frequently came ashore near one or other of the LOPs where they would be assisted and comforted by the Volunteers on duty, who rapidly summoned the emergency services.