Carnage and death on the 7.15pm train from Macroom

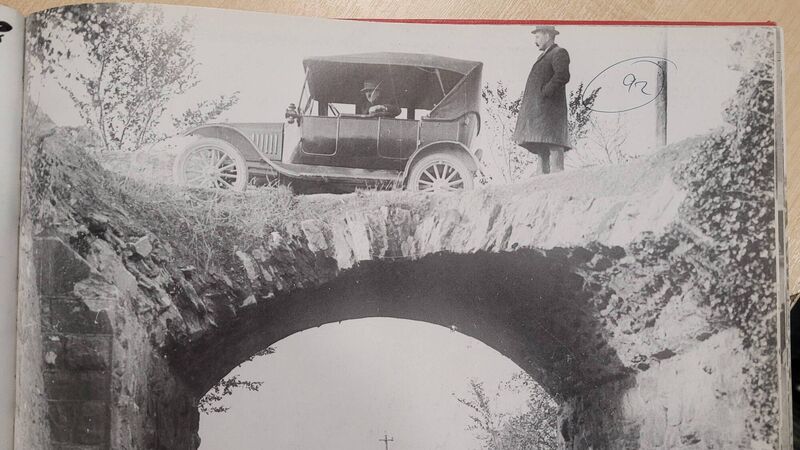

Curraheen railway bridge in 1922, after it was damaged during the Civil War - the fatal train crash occurred close to here in 1878

ON that fateful September Sunday in 1878, a young boy called Denis Burke had set out to Macroom to ensnare some birds.

****** In the immediate aftermath, the railway company claimed the train was “maliciously thrown off the track”, suggesting vandalism. However, this theory was swiftly rebutted, not least by outraged local residents who “protested loudly against such an imputation on their character”.

It quickly became clear that the poorly maintained sleepers were to blame.

At the inquest in Ballincollig Schoolhouse, James Rattray Jnr, son of the dead driver, said he had been acting stationmaster at Cork station on the evening of the crash and had seen off his father to Macroom at 6.15pm: The last time he saw him alive.

Patrick Kidney’s brother, William, a porter at Beamish and Crawford brewery, told the inquest he had meant to accompany Patrick that day but hadn’t gone.

When he heard of the accident, he went to Curraheen but couldn’t face seeing his stricken brother. “I saw a lot of women lying on the ground moaning and crying. I saw my brother at a distance - but I couldn’t go near him - I hadn’t the heart. I was going up towards him but my nerves got weak and I turned back.” Mary Drew, widow of tailor Michael, had been the victim of a terrible misunderstanding on the night of the tragedy.

She had met the damaged train when it later limped into Cork station with some of the lesser-injured passengers. When she saw her husband was not on board, she assumed he had survived and was “frantic with joy”.

The Examiner reported: “No-one, not even the boldest, had the heart to tell her that her bread-winner lay dead a few miles away, but when at last she learned the dreadful news, her agony of grief was terrible to behold, and as she shrieked, many a manly cheek was wet with tears.” Interestingly, the press gave ages for the males injured, but not for the females.

****** An accident report into the tragedy was carried out by D. F. Sullivan, of 7, Winthrop Street, and defective sleepers at the spot where the engine left the track was given as the sole cause.

The blame lay squarely with the Cork & Macroom Direct Railway, and public outrage was aroused when it emerged that, just a few weeks beforehand, its chairman, W. Hutchinson Massey, boasted at the company’s half-yearly meeting that the business would “get the last shilling out of every sleeper”.

A year before, he had scoffed at any prospect of a crash on the Macroom line, as it was such a “simple” route. Both remarks came back to haunt him.

The inquest found that the company directors were culpably responsible for the accident. This was tantamount to an accusation of manslaughter - and was a terrible stain on the reputations of people like famous poet Denny Lane, Secretary of the Cork Gas Consumers, and Sir John Arnott, one-time principal proprietor of the Irish Times. Some of the directors were even brought into custody No criminal charges ensued, but the company had to pay £15,000 compensation to the injured and relatives of the dead.

Even in defeat, W. Hutchinson Massey scoffed at the number of injury claims, and suggested the figure of 78 should be closer to 20.

He sarcastically stated he was glad that many of those “who received severe spinal shock in the crash were again walking around quite well since their cases had been disposed of”.

In 1978, in an Echo article marking the centenary of the disaster, railway enthusiast and former Holly Bough editor Walter McGrath pinpointed the exact scene of the crash: “If you turn northwards at Curraheen village and take the narrow road to Minister’s Cross, and Ballincollig, you soon cross over the Maglin stream. Just beyond that was the railway bridge, and on your right, is the exact spot.” The journalist said that his grandmother, who lived in Ballincollig at the time, recalled it was the greatest tragedy in the district and remained in the minds of all who saw the scene of destruction.

****** The Cork & Macroom Direct Railway line opened on May 12, 1866, and ran for 24 miles, with stations at Bishopstown (short-lived), Ballincollig, Killumney, Kilcrea, Crookstown and Ryecourt (or Crookstown Road), and Dooniskey - the latter platform is still visible, on private land.

It began with three passenger trains each way on weekdays, later increased to four, with two return trains on Sundays. Daily goods trains also ran, with additional monthly cattle specials and occasional grain runs.

Passenger traffic ceased in 1935. Eight years later, plans for a special train for a Sunday sports meeting in Cork had to be scrapped due to overhanging bushes.

On June 13, 1950, however, a group of Irish Railway Record Society members were conveyed from Macroom to Cork in a six-wheeled carriage attached to the monthly livestock train.

The last train to use the line was the Fair Day Special of November 10, 1953. The tracks were lifted the following spring.

THE Curraheen crash of 1878 was marked this year, when a memorial stone was put up near the spot where it happened.

Derry persuaded Munster Agricultural Society (MAS), who own the land, to pay for a memorial stone to be erected at the scene, on land near to where the animals are judged in the annual Cork Summer Show.

Sadly, Derry died in Marymount Hospice last November after a brave battle against cancer, and did not live to see it erected. However, his friend, Tommy Wallace, who works for MAS, said: “Before Derry died, I brought the monument up to Marymount so he could see it. After that, he could go to sleep, happy in the knowledge that those who died in the Curraheen crash had been remembered.”

Derry believed that six people, rather than five, died, and the ‘Master Kenny’ named on the memorial may refer to a child who died later of his injuries.