Blown up... then rebuilt: Story of Mallow Viaduct 100 years on

A steam train crosses the Mallow Viaduct to mark the 150th anniversary of railways in Cork

IT has been argued that recognition by the IRA of how essential railways would be in a post-conflict Ireland, tempered their attacks on the network during the War of Independence.

If this was so, that belief was abandoned as the Civil War continued through 1922 and into the following year.

What started out as strategic attacks on bridges to stem the advance of Free State troops degenerated into a free-for-all, as the National army regained territory pushing southwards.

By March of 1923, just two of the six lines out of Cork city were operable, with only the Cork-Youghal line not having a break in its journey.

There were daily attacks on the rail network, including derailments, blowing up of bridges, looting, shooting at and commandeering of trains, and burning of stations, signal boxes and rolling stock. Wrecking locos by staged crashes or derailments was also carried out.

In late 1922, the Great Southern and Western Railway (GS&WR), who ran most mainline rail services in Munster, announced that they were ceasing all services on January 8, 1923, due to acute financial difficulties, but the fledgling government agreed to cover the deficit in day to day expenses .

The State now effectively controlled the railway, and a limited timetable was maintained.

No single act of sabotage during this conflict, however, is believed to have caused more hardship and disruption to the wider community than the blowing up of Mallow viaduct in early August, 1922, which left the country’s two largest cities without direct rail communications for 14 months.

Of the three viaducts that had to be built to bring the Dublin-Cork line from Mallow into Cork, Mallow was the largest, spanning the Blackwater valley just south of that town’s station.

Built through 1848-49, it is recorded that people came from all over Munster to marvel at its construction. It was described as a magnificent cut-stone structure with ten 60ft high arches.

By 1880, Mallow was a busy four-way junction with direct links to Dublin, Cork, Tralee, and Waterford, increasing the viaduct’s importance as a vital piece of regional and national infrastructure.

Returning to 1922, and in early August Anti-Treaty forces still held Cork and Kerry, but an assault by the National army was widely expected; how it came, however, was not - by sea.

Three vessels were commandeered by the National army and the largest, carrying 450 troops, landed at Passage early on the morning of August 8. Later that day, the other two left Dublin port for Youghal and Union Hall.

This development threw the Irregulars into disarray as a sea-borne attack does not seem to have been anticipated or planned for.

In spite of stubborn resistance by the Irregulars in the Rochestown and Douglas areas, the National army re-took Cork city without another encounter.

When news of the landings reached Mallow, Anti-treaty forces quickly withdrew westwards, but before they left, they blew up the railway viaduct on August 9.

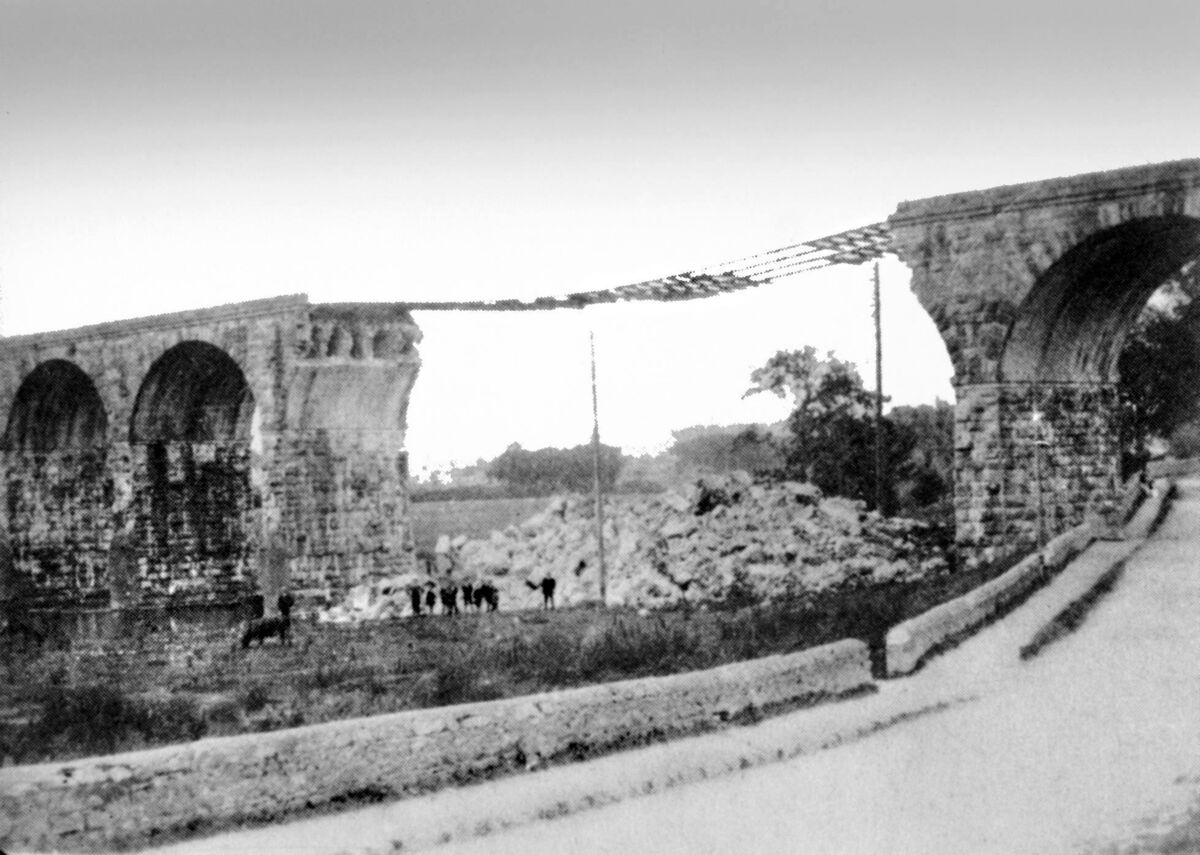

The force of their high-powered explosives completely destroyed the three northern arches and caused the eventual collapse of most of the others. What was left had to be demolished soon after.

The fall-out was instant, Cork was now effectively cut off from the rest of the rail network.

A temporary station called Mallow South was hastily constructed within days on the southern side of the valley. From here, a local train service brought passengers to and from Cork.

The unfortunate travellers had to transfer between the stations by whatever road transport they could arrange or hire.

What must be remembered is that the nearest road bridge to the railway back then was at the opposite end of the town to the railway, so the journey was quite an inconvenience.

A carrying firm, Wallace and Co., took up a contract with the railway, to transfer mail and passengers, but photographs show a variety of vehicles employed including jaunting cars and Ford Model Ts, suggesting perhaps some spontaneous local enterprise.

Meanwhile, thoughts turned to rebuilding the viaduct.

The Government wanted its reconstruction to be carried out as quickly as possible, but the GS&WR entered into a contract with Arrols of Glasgow to put up a temporary bridge costing £18,125, while they would also replace the original viaduct, presumably as it was, in stone.

The Government, however, instructed Professor Crowley, a native of the Mallow area and who was to observe the rebuilding on behalf of the State, to advise Arrols of its withdrawal from the contract.

The bridge-builders received £293 7s 5d to cover expenses incurred. As the taxpayer would ultimately foot the bill, the State felt the cost of the temporary bridge would be better used to be put to a permanent replacement.

There were also economic and political reasons for the work to be expedited - the only way goods and livestock could be moved to and from Cork was by sea.

Tenders were now invited for a contractor to, in the briefest of time, supply and erect a permanent bridge. This was awarded to Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with a local firm getting a separate contract to prepare the footings for the new steel trestles.

Speed was indeed the watchword for, under military protection, the work was completed in nine months.

Construction of steel bridges had reached a high degree of standardisation by then, so much time on design, etc, was saved.

When GS&WR directors visited the site in September, 1923, the most southerly of the ten 51ft spans was already in situ.

On Thursday, October 4, the last one was put into position, completing the structure. Track laying and test runs quickly followed, to the satisfaction of all parties.

It was agreed that a grand reopening should be held and, on October 16, President of the Executive Council W. T. Cosgrave arrived at Mallow station to reopen the viaduct.

He and Sir William Goulding, of the GS&WR, boarded the engine and the train moved slowly onto the viaduct. Spontaneous cheers and applause erupted as the loco cut through tricoloured bunting placed across the track, which was also lined by National troops.

At a celebration dinner later, in Morans Hotel, Mallow, tributes were paid to all parties involved in the project.

With direct rail services now restored, a new, faster timetable was introduced, along with improved mail services.

A contemporary Cork Examiner article captures the relief felt by all affected by this mainline severance.

“All travellers who have had to negotiate the gap between Mallow South and Mallow North frequently will long remember the rush and general confusion and incidental expenses, but this was nothing as compared to the loss occasioned by the impossibility of sending goods and cattle direct.”

This year, this steel viaduct will be functioning 100 years and, while politically these are more peaceful times compared to during its construction, the viaduct is now handling more traffic than at any time in its, or its predecessor’s past.

Yet it’s hard not to lament that, if time had allowed, a replacement viaduct in stone could have been built.