John Dolan: 40 years on, why it’s wrong to mock ‘moving statue’ pilgrims

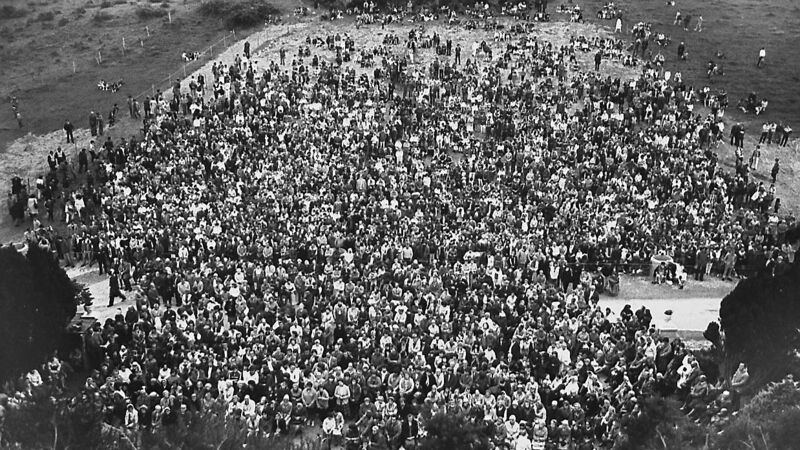

A mass of people at the grotto at Ballinspittle in mid-August, 1985 - a full month after the original sighting’

That in itself sounds quaintly old-fashioned to modern ears, but what happened next would send shockwaves across the country.

The mother claimed she saw the statue of the Virgin Mary at the grotto moving - she later told television news crews that it appeared to her to be “breathing or sighing”, and that she had been overcome with a sense of peace and protection.

Thus began the phenomenon - 40 years ago next week - of what became known as ‘the moving statue of Ballinspittle’.

Among the pilgrims - the ones who believed, or wanted to believe, in this miracle - were a family who lived in the same street as my wife in 1985, in Leixlip, Co. Kildare.

They embarked on a 600km round trip in a single day, way before motorways, armed with a heap of hang sangwiches and a flask of tay, just to join the crowds in Ballinspittle and to hopefully glimpse this miraculous vision of Mary.

You can picture them now, sat among hundreds of others for hours on end, training their eyes and gazing unblinkingly at the statue.

Did she move?

I swore I saw something? What about you?

No, but keep looking...

Many of those who gathered believed they did witness the miracle of the Virgin moving.

The phenomenon at Ballinspittle lasted the entire summer - even though it was a poor, wet one. Indeed, the contagion spread - there were reports of similar moving statues in around 30 other sites as Catholics fixated on the shrines to Mary that dotted the country, many of them built in the Marian year of 1954 three decades earlier.

Looking back through the lens of four decades of great upheaval and change in Ireland since 1985, it is easy to mock those who played a part in the ‘moving statue’ phenomenon, to dismiss the participants as poor dupes who put a great store in their faith, and to pour scorn on their need for some kind of proof in a higher being.

But to do so would be wrong on many counts, and it would be doing our recent forebears a disservice - not least because the events at Ballinspittle, although on the surface appearing to be a part of the Catholic tradition in Ireland, were actually, in my eyes, a reflection of a far older belief system.

The phenomenon of summer, 1985, speaks to me as being in communion with an Ireland that pre-dated the arrival of Christianity - to an age of standing stones and holy wells, of fairies, and superstitions that still hold to this day.

This mass exodus at Lughnasa was a calling, a beckoning to spiritually and physically connect with fellow Irish brethren.

The rosary beads that threaded through the fingers of those watching the statues at Ballinspittle may have been a symbol of Catholic Ireland, but the spirit at the heart of it was defiantly hibernian, not Roman.

After all, back in 1985, the Catholic Church hierarchy in Ireland hardly embraced this apparent proof of God on their doorsteps. Far from it, they positively discouraged the pilgrims.

Pope John Paul II, six years after his visit to Ireland, said nothing, and the Church never endorsed the events in Cork.

Which strikes me as strange, from the vantage point of four decades on - as does the refusal of the Irish to heed their calls, and to congregate anyway. Aren’t we taught that the Church had its flock in a vice-like grip in those days?

If the typical Irish Catholic in 1985 was so wedded to the faith, and hung on every word uttered by the priests and bishops, why did 100,000 of them simply continue with their pilgrimages of devotion and blithely ignore the naysayers?

Similarly, when UCC bigwigs expounded a theory that explained away the ‘visions’ as optical illusions caused by staring at objects in the evening twilight, the devotees simply ignored the rationality and kept on congregating.

The pull to Ballinspittle was stronger than the pull of Church and science; it was a call to collective unity, a call to belong to something... else, something buried deep in the national psyche, far away from the statues of Jesus and the confessional boxes. Mary might as well as been St Brigid in that grotto - the version of Brigid widely believed to be a Celtic goddess throwback.

While the Catholic apparitions at Lourdes, Knock, and Fatima a century earlier, and at Medjugorje just four years before the Ballinspittle incident, have become articles of faith for the religious hierarchy and its followers, the Cork ‘vision’ has been brushed aside.

The pilgrimage reached back to an ancient need in the summertime days of plenty to take a time out and embark on a trek, a chance to mingle and gossip with your brethren.

Did the statue move that summer in 1985? Does it matter? It moved the people of Ireland in a way it never moved the priests and bishops who spent every Sunday urging their flocks to always have faith, always believe, that God is all around us - then decided he was certainly not embedded in a statue in Cork.

The pre-Christian traditions of Ireland are never far from the surface, and continue to have a hold on us.

My Echo colleague Jo Kerrigan - she of Throwback Thursday fame - has a particular interest in it, and recently released a book, Irish Fairy Forts: Portals To The Past, which hit No.1 in the Irish non-fiction chart.

Curiously, this has prompted a wave of sales for her previous books, and Old Ways, Old Secrets: Pagan Ireland, and Brehon Laws; The Ancient Wisdom Of Ireland have now re-entered the top ten book chart too.

I doubt books on Christianity would have the same hold on us today, do you?

App?

App?