Vote for freedom in next general election

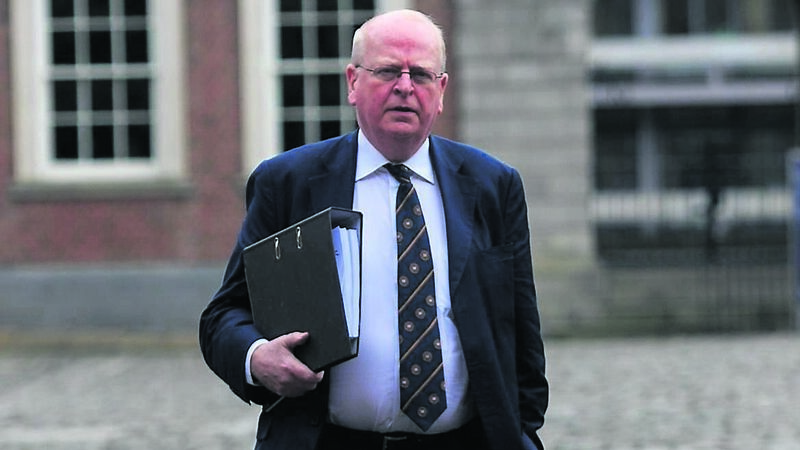

Michael McDowell is among those who opposed the Hate Speech Bill

A little over a century ago, a series of articles by Terence MacSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork, were published in a collection entitled Principles Of Freedom.

The preface of the book was penned by MacSwiney in September 1920, in Brixton Prison, London, where he had already begun his hunger strike which would make him an international figure, and assure his place, along with his predecessor Tomás MacCurtain, among Cork’s most famous sons.

It is no exaggeration to say that Principles Of Freedom was a parting gift by MacSwiney to his country and to posterity. An exhilarating book, it has retained its relevance and popularity as our current generation continues to unpack the legacy of this remarkable Cork man.

Freedom has again come in to focus for reasons scarcely imagined even in the relatively recent past.

The Constitution of Ireland, adopted in 1937, provided a very strong protection for human rights and civil liberties. It was an era when both fascism and communism were on the rise and when the latter would proceed to dominate Eastern Europe after World War II.

In the countries so affected, absolute state control was the pervading method of rule.

In the context of its times, the Irish Constitution was a refreshing statement of essential rights, as well as a blueprint for democratic representative Government and a well-working public administration.

It was considered settled policy that while the Government of the day was entitled to a robust mandate to conduct the business of State, there were thresholds to its power and overreach was not acceptable.

Consultation with the people was required by way of referendum when it came to any alteration of the fundamentals of societal self-determination or to sovereignty.

Emergency powers

The Emergency Powers which were ushered in during the pandemic in March, 2020, and which lasted until March, 2022, signalled a change in governance for the Irish.

While the State had an undeniable duty to respond to the threats to health, the abandonment of legislative scrutiny over a raft of issues affecting normal life for a period of up to two years was unnecessary and disproportionate.

Any protest against the draconian restrictions was viewed as not far off treason, even when the measures complained of were objectively absurd or not replicated in other democracies.

The Hate Speech Bill followed closely on the Emergency Powers and the “loose language” of the Bill was very troubling, in the opinion of the former Attorney General and Justice Minister Michael McDowell.

Under sustained public criticism and political pressure, including from its own ranks, the Government withdrew the most controversial sections of the bill.

Mr McDowell commented: “If you look right across the world, people are being prosecuted on very flimsy words... we can’t have language which restricts people’s freedom of expression and leaves it to judges to decide it in the end.”

X Platform (formerly Twitter) owner Elon Musk, who is outspoken on such topics, told his 200 million X followers that the Irish bill was an “attack on freedom of expression” and offered to fund legal challenges.

There’s little doubt but that the legislation in its original form would have represented a serious attack on free speech and prove an unacceptable form of censorship. Interestingly, much of the critique of the negative aspects of the Bill came from the Seanad or Upper House, which just over a decade ago it was proposed to abolish, a move wisely rejected by the electorate.

Pandemic treaty

A further development with at least some implications for freedom would be the signing of the Pandemic Treaty proposed by the World Health Organisation in the wake of the covid pandemic. The Treaty is still in the planning stage having failed to secure an agreement earlier this year.

The Health Minister has been adamant in his support for the proposed Treaty, but declines to say if he believes a referendum is necessary. Many believe it is essential that any such Treaty’s provisions should include a statement of commitment to human rights and civil liberties, often neglected in the management of the covid pandemic.

Without such a balance, preparedness for a health threat could hardly be deemed adequate and there would be a failure to learn from the mistakes of the recent past. This is even more necessary since the State has failed so far to provide an inquiry into the management of the pandemic here.

Irish people have a right to the most comprehensive public consultation, namely a referendum, before the Government can commit to an international Treaty, a principle established by the Courts in the Crotty Case of 1986.

Those aspiring to govern seek as a matter of course the right to lead the country in economic matters and regularly go in to scintillating detail as to how they would manage the public purse. This has been part of the cut and thrust of our election campaigns over decades.

Those running for office today will not just be in charge of our economic assets. There is another prized civic possession they may well end up controlling and that is our freedom and self-determination. We would do well to scrutinise candidates' and parties’ plans in this regard, as much if not more that we would those of the economy. The implications for freedom may be more subtle than they were over a century ago, but they are no less real.

App?

App?