Where was the love? Mother and baby home horror shames our nation

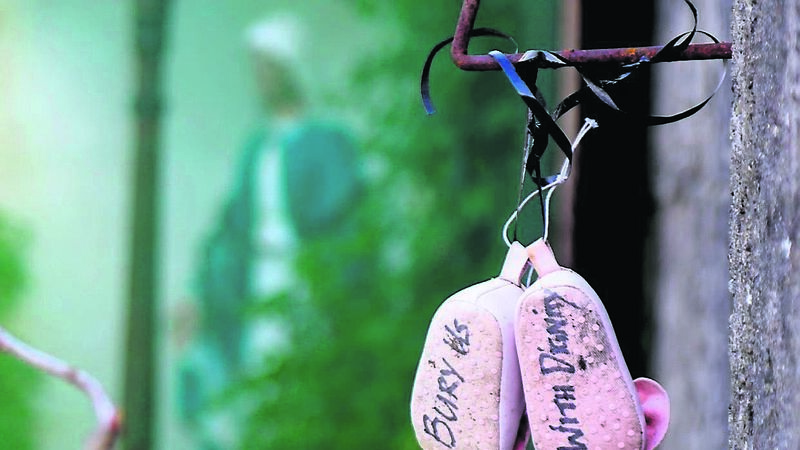

A pair of baby shoes with a message hanging at the walls of the Mother and Baby home burial site in Tuam, Co. Galway

This was the early to mid-eighties, and there was a lot of green space between these buildings, each of which constituted a different department, which together formed the hospital network.

Over three or four years, I worked in several of these buildings, doing a wide variety of seasonal jobs which ranged from working in the hospital laundry to assisting permanent staff through various roles in, for example, geriatric and maternity wards.

One summer I was allocated to a job in a corner of the complex I had never even seen before. Often during my breaks or in the late afternoon as I finished work, I would notice the same people ambling around the green areas between the buildings. They didn’t appear to be staff or visitors, nor did they appear ill or in any way debilitated, which probably meant they weren’t patients either, although some were (to my young and untrained eye anyway) possibly in the older-middle-aged category, while others I would have described as perhaps elderly.

All of them appeared to be very familiar with the hospital grounds. There was something about these people I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Looking back, the best way I can describe it is that there was a kind of wary remoteness about them. If you nodded or said hello, they would always salute you back. But they never came close to you. They kept their distance.

As the summer passed, I got to know some of these people on sight. Eventually I asked a permanent employee about them as we stood outside on our break enjoying the sunshine. The answer rocked me back on my heels. These, my colleague said quietly, were the children of single mothers who had been sent to the hospital for their confinement, 50, 60 or even 70 years previously. These now-adult children still lived on the hospital grounds, she said. “But,” I said, astonished, “did they never leave and go to college and get jobs?”

Others had held down jobs, but even when they worked outside, still came home to the hospital at night.

I was only about 18 — in those days many school-leavers actually started college at 17, and, as I recall, this was probably only my second summer in the hospital. To my eyes, it was located in what was for the time at least, quite a large, busy, modern Irish city buzzing with the concerns of 1980s life. But these people seemed, to my young mind, like a throwback to the times of Oliver Twist, so what this woman was saying was utterly beyond my comprehension.

“But why are they still here?” I asked. “Where did their mothers go?”

She just looked at me.

“What about their families?” I asked.

“Didn’t they have uncles, aunts, cousins and grand- parents; you know, people like that?”

So she put it euphemistically and simply, as you would to a child.

“Their mothers might have had to go to England,” she explained.

“Their families could all be dead now. Or maybe these poor people have been forgotten about.”

I looked at her, open-mouthed. “But why?” I said again. I must have seemed like a four-year-old. She didn’t say anything else; I imagine the poor woman didn’t know what to say.

Because what these people were, I now believe, were the adult child survivors of the era of the Magdalene Laundries. Here I was — a young, independent, female, getting to go to college, looking forward to a good job and a car and being independent in the world. Becoming pregnant outside marriage was still a big stigma in the ’80s.

What I was seeing each of those summer afternoons was a glimpse into a repressive and terrible era of misogyny, abuse, discrimination and cruelty in which families, society, the government and church had all been complicit. And these people had lived the result of that all their lives.

I must have looked as horrified as I felt as my colleague explained that things were much better for them now. The matron — whom I had met briefly when I was hired — was very good to them altogether, my colleague said.

“She is very kind to them,” she said. “Very kind altogether.”

She stamped her fag out on the grass and went back to work. I followed, my mind whirling.

We have now all heard of the Magdalene laundries; of how pregnant women were incarcerated and forced to do what nowadays would be categorised as slave labour for the crime of conceiving outside wedlock; we’ve heard the stories of heavily pregnant girls who were, for example, put kneeling for hours to scrub the floors of endless hallways. But apparently, this week’s Mother and Babies Homes report could find very little evidence of physical abuse, despite all the witness reports.

Sure, how could you find evidence? Where could you possibly expect to find solid proof that a pregnant girl was ordered onto her knees with a bucket and scrubbing brush? Sure, the nuns would hardly have been taking photographs or recording the number of slaps per day that they doled out, now would they?

How can there be this bland assertion that these women were subjected to emotional abuse (presumably without solid evidence, because how could there be) but that at the same time there was little evidence of physical abuse? It doesn’t make sense.

And anyway, how you could not count the physical separation of so many mothers and babies as physical abuse, especially as anyone with an eye in their head could see it must have often been forced?

Because even if you insisted that, statistically, some girls would leave their babies willingly and depart for London, surely, even in the most disingenuous, not to say optimistic interpretation of this hellish picture of a religious Irish version of The Handmaid’s Tale, one could not ignore the obvious — that 56,000 young mothers leaving their babies behind absolutely screams out coercion.

At the same time, it says most women had no alternative, blandly ignoring the fact if the government, society and families didn’t provide an alternative to these awful places, then the women were forced.

On top of that, the report states that women were brought to homes by family without being consulted — isn’t that blatant coercion? It finds that many women contacted State or church agencies seeking assistance as they had nowhere to go and no money.

And why did they have to do that? They had to do that because the fathers, Irish society, their own families and their government did not assist or in any real way, support them and their babies.

This report is going around in circles as it somehow, and for some reason, doesn’t want to add two and two together and get the right answer, that all of this screams coercion.

Where, in all this, we should ask, were the fathers? Those men who had consensual sex with, raped, or committed incest on these girls? Where was the State? Where were the great and the good of society? Where were their families?

And most of all, where was the kindness, mercy, love and compassion that is supposed to be the foundation of a church which, in so many cases, incarcerated, victimised, abused and shamed these girls?

App?

App?