Cork v Waterford: Sporting rivalry put aside to support Déise's Brian Greene

Corks Joe Deane is tackled by Waterford's Brian Greene in the 2003 Munster final. Picture: Eddie O'Hare

In his excellent book ‘ ’ Dónal McAnallen eloquently describes the wake of his brother, Cormac, in March 2004.

As an endless line of people came to Eglish to offer their condolensces to the family, the queue kept getting longer as the evening grew darker. When Dónal McAnallen looked through the in-house book of condolence years later, he saw signatures from 30 of the 32 counties that week.

So many players and managers came from every corner of the country that McAnallen could tell the story of modern Gaelic football through some of the visiting sympathisers; nearly every All-Ireland winning team of half a century was represented, beginning with Brian Smyth, who captained Meath to the 1949 All-Ireland.

McAnallen listed some of the All-Ireland winning names, ranging from Kevin Heffernan to Seán O’Neill to Mick O’Dwyer to Colm O’Rourke to Seamus Moynihan to Kevin Walsh. The Armagh team of 2002 didn’t have to travel as far but McAnallen noted that every one of them “were there to a man”.

Of the many different memories from that intensely sad occasion, the image of the Armagh and Tyrone players lining up together to form a guard of honour was one of the most vivid.

“It represented a huge mark of respect and was always something we appreciated as a group,” wrote Mickey Harte in his second autobiography. “Armagh recognised the important things as footballers and as people. We will always be grateful for what they did that day.”

During an epochal era for football in the early 2000s, the Armagh-Tyrone rivalry was one of the defining parts. The relationship on the field was spiked by enmity and discord.

When the sides met in the 2003 All-Ireland final six months earlier, the whole occasion was loaded with more local tension and bitterness than any previous All-Ireland final. It devastated Armagh to watch Tyrone beat them in that final but when tragedy struck the McAnallen family and the Tyrone footballing community, Armagh put all that past history to one side for the greater good.

The sporting public have always rallied around fallen or struggling heroes but it’s a unique trait in the GAA how tragedy or ill-fortune can often heal rifts and bring bitter rivals closer together.

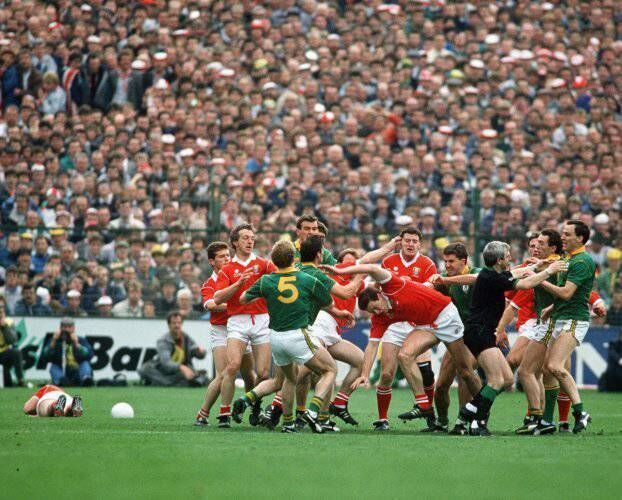

Sport is often so tribal that it takes a sad event to finally bring warring tribes together. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Cork-Meath rivalry was ferocious. The teams met in three All-Ireland finals (the 1988 final went to a replay) in four years and some of those games were poisoned by bitterness and bad blood. “There were good days, sad days, mean days and the odd great day,” wrote Colm O’Rourke before Meath and Cork met in the 1999 All-Ireland final.

The bad blood between both sets of players lingered for over a decade until it took the saddest day of all to finally melt the tension and animosity. When John Kearns, goalkeeper on that Cork team, passed away in 2001, many of the Meath players travelled to the funeral. It was only when the players got chatting afterwards that they realised how much they had both forgotten about that bigger picture.

It’s never easy to dilute the obstinance and ruthless single-mindedness which breeds disharmony between bitter rivals but hard times, and that inane goodness and willingness to help those on one side in their time of need, invariably does.

The Cork-Waterford rivalry of the 2000s never had that spikiness. It was one of the most glorious rivalries in the history of the sport because it produced so many epic and enthralling matches, with the 2004 Munster final rightly considered as possibly the greater Munster final ever.

When Brian Greene was diagnosed with lung cancer two and a half years ago, and his family needed more help and support, it was almost apt that the Cork hurlers would provide as much assistance as they could.

The proceeds of the Cork-Waterford challenge game that takes place today at Fraher Field, with tickets priced at €10, will go towards the Greene family and chosen charity Waterford hospice.

And yet, this is about much more than just fundraising. “It doesn't matter who you are or what you are when you are in the GAA, it is democratic, equal,” said Jim Greene, Brian’s father, on the night in November that the game was launched in Dungarvan.

“This is humbling from a family point of view. To get to where Brian got and then to see the support you have around you, it is a great boost for him. People in these positions, they need help. A family can't deal with this on its own. There has to be outside help. There needs to be this type of encouragement and love and respect coming. That lifts everyone.”

With no pre-season competitions anymore, with the Cork hurlers not having played since the All-Ireland final in July, and Waterford not having played since May, the hurling public are voracious at this stage to watch inter-county games again.

Brian Greene will be there. So will some of his former team-mates, along with some of the Cork players they once waged war against.

And the way Cork and Waterford have come together again reveals the respect and integrity that made the rivalry great in the first place.

App?

App?