A telegram of doom, and one sailor’s lucky escape: When 8 Cork people died at sea

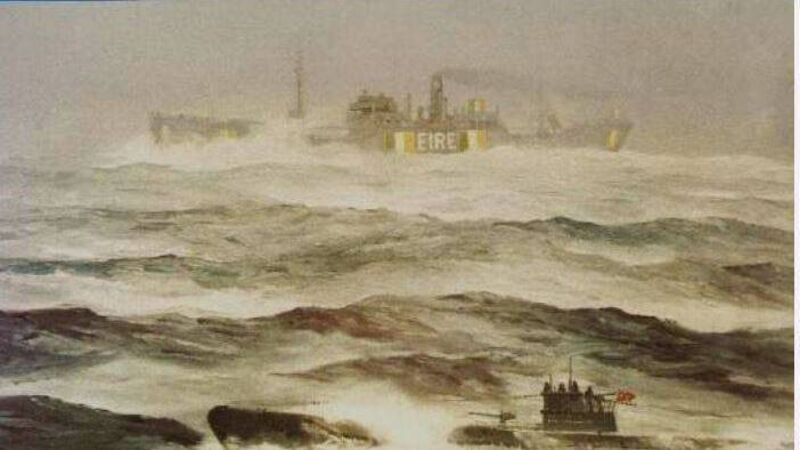

A painting of the Irish Pine sinking in 1924, in the National Museum of Ireland at Dun Laoghaire.

In the early days of December, 1942, a telegram arrived at the Cusack household at 105, Evergreen Road in Cork city.

Mrs Cusack, a mother of two young children, gave a secret smile. Her husband at sea had a habit of sending telegrams for their children’s birthdays, and their son Vincent was three in a few days’ time.

But when she read the telegram, her life was turned upside down in an instant.

Her 50-year-old husband, Thomas, was chief steward on the Irish Pine, and she was told the vessel had been out of contact for weeks, with all 33 crew presumed lost.

Thomas left behind a daughter Philomena, aged six, and little Vincent, who would never see their daddy again.

Around the same time, just 3km away, on the northside of Cork city, Jeremiah Carroll must have been hearing the same terrible news and thanking his lucky stars.

Jeremiah, of School Avenue, Gurranabraher, had been signed up for the Irish Pine’s last voyage, but, by a twist of fate, did not arrive in time to set sail. Did he sleep in? Did his alarm call fail?

In the tragic roulette of life, Jeremiah’s last-minute replacement, Kevin Cashin, a 21-year-old Dubliner, also perished on the Irish Pine. Such cruel fate...

******

The largest single loss of life suffered by the Irish merchant navy in World War II occurred off the coast of Canada on November 16, 1942. In the space of three minutes, the entire crew of the S.S. Irish Pine perished at the hands of a German U-Boat.

No bodies or wreckage were ever recovered.

Eight of the 33 who went down near Cape Breton Island were from Cork. Today their names are listed among the 150 men — 136 merchant seamen from 16 ships and 14 fishermen from two trawlers— who lost their lives between 1939 and 1945, on a memorial on City Quay, Dublin, that was unveiled in 1990.

World War II claimed millions of lives but the loss of this group was particularly poignant given they were from a neutral country during the so-called ‘Emergency’.

News of the ill-fated Irish Pine didn’t reach the Irish public until Saturday, December 5, 1942, 18 days after the sinking, when a statement from the owners, Irish Shipping Ltd, was published in the national press announcing “that the SS Irish Pine is now so considerably overdue at her transatlantic port that she must be presumed lost. Next of kin have been notified.”

The following Monday, the flag over the Cork Harbour Commissioners’ office was flown at half-mast out of respect.

The Irish Pine had been chartered by Cork fertiliser firm W. & H. M. Goulding Ltd, to bring a cargo of phosphate rock from Tampa in Florida, USA. It was her fifth trip across the Atlantic under the Irish flag.

The 33 victims came from across Ireland, but the tragedy was most acutely felt in Cork, Dublin, Limerick, Wexford, Louth and Galway.

The age spread ranged from 18- year-old Eamon Donagh from Galway, to donkeyman — the person in charge of the ship’s engine room — 60-year-old John Nolan, from Fairview, Dublin.

Given that 22 of the 33 crew were under the age of 40, it is no surprise that several were married with small children. The loss of the bread-winner must have made life very difficult for the families left behind in the ration-hit Ireland of the time.

Thomas Cusack, the man who lived in Evergreen Road, had spent almost 25 years at sea, on the SS Innisfallen, SS Ardmore and SS Kenmare, and also had a stint on the U.S liner Manhattan.

The other seven Cork victims were:

George O’Brien, 39, of 3, West Beach, Cobh, who left a wife and a baby of six months. The Irish Pine’s Chief Engineer, he had spent nearly all his working life at sea.

The story of Second Mate Alfie Hartnett, 50, of Youghal, is rendered more heartbreaking by the fact the widower with three children aged 13, 10 and 8 had remarried just two months before departing, on September 18, 1942.

The Assistant Steward, Cork city man Michael O’Callaghan, 26, an only son, was a member of Cork Operatic Society and had previously worked in a Cork hotel as a waiter.

Second Engineer, James O’Connell, 46, of 26, Parnell Place, Cork, who had already survived one attack at sea two years earlier. In 1940, his ship was sunk in the Mediterranean and he spent four hours in the water before being rescued off the coast of Greece. James left a wife, who was licensee of the White Horse Inn in Parnell Place, Cork, and two sons.

Third Mate William Connolly, 31, of Lower O’Connell Street, Kinsale, whose father was also lost at sea, during World War I. William had witnessed the Dunkirk evacuations of 1940.

Kinsale also lost Greaser John McCarthy, 48, and Able Seaman Patrick Sheehan, 38. McCarthy was married with a family who lived on Bandon Road.

******

Ireland’s shipping fleet was ill-prepared for war when it broke out in 1939. To address this, the Government set up Irish Shipping Ltd in March, 1941, and one of the first vessels procured was the Irish Pine, which had begun its working life in the USA in 1919.

The vessel had already hit the headlines in August, 1942, when it rescued 18 survivors of a torpedoed British ship, the Richmond Castle, off the southern coast of Ireland, bringing them safely ashore in Kilrush, Co. Clare.

Three months later, it was no more — its fate remained unknown for decades, and an Irish Press article in 1952 referred to the “mystery of the Irish Pine”, but the likelihood of it being sunk by a Nazi U-boat was strong.

The truth finally emerged in 1977. Naval historian Frank Forde, while researching in the Naval Historical Branch of the UK’s Ministry of Defence in London for his book, The Long Watch, discovered the secret diaries of U-Boat Commander Rolf Struckmeier, a distinguished operator who had been awarded Germany’s military decoration, the Iron Cross in September, 1942.

The diaries revealed that, in the early hours of Monday, November 16, 1942, the S.S. Irish Pine was on its way to Boston for repair works in the midst of a blinding snowstorm.

Struckmeier’s U-Boat, U-608, had spotted the 5,621 ton steamer the day before and the Irish Pine adopted zigzag movements to navigate its way to Boston. She was carrying the mandatory neutrality insignia, the Irish Flag and had the word ‘Éire’ emblazoned on her side, but Struckmeier claimed he never saw this.

He stalked her for eight hours, frequently losing her in rain and snow squalls, and eventually, at 7.15pm, released the torpedo in rough seas, which hit the target. In three minutes the Irish Pine and its 33-man crew were sunk.

Each of the lost had their own personal stories and left grieving family and friends.

The six Limerick victims included Assistant Cook Hector Young, aged 20.

In 2005, it was discovered that Hector was the only one of 16 Limerick Merchant Navy sailors who lost their lives at sea during World War II not to be posthumously awarded the Mercantile Marine Service Medal by the Irish Government.

His sister, Rebecca Clarke, of Ardnacrusha, accepted the medal on his behalf.

The error had been spotted by historian Pat McNamara, who said: “During the emergency, Ireland as an island nation was solely dependent on her small mercantile marine and fishing fleet to sustain her with the necessities of life.

“These men were volunteers and the service in which they served was a civilian service. These men manned the ships that supplied the country with the food and fuel that helped to sustain this island nation during the dark days of World War II.”

In January, 1943, Monaghan poet Patrick Kavanagh added his tribute to the lost seamen.

The Irish Pine

She has harboured in the Unknown

That we all sail unto

And send no message back

No more than this ship’s crew.

Vain hopes to be remembered —

We brought you wheat.

And two months gone, forgotten

In hall and field and street.