Heavens above! The Cork highway to hell plan remembered... 50 years on

THE ONLY WAY WAS UP: St Patrick’s Church on the Lower Glanmire Road, with a modern rendition of how the proposed road network might look today, if it had gone ahead. Image: Viktor Gekker

I HAVE a distinct memory of when I was a five-year-old boy. It’s 4pm on November 2, 1968, and I’m in the back seat of our family’s Triumph station-wagon in Cork city, sat for three hours while my father waited, waited, and waited to turn right onto Merchant’s Quay.

The stench of raw sewage in the Lee combined with leaded petrol fumes meant this was no place to be stuck in a car.

Anyone who grew up in Cork in the 1960s was certain of two things. We were good at hurling, and the traffic was dreadful.

Huge jams were a regular occurrence, as cars, buses, lorries and cyclists jostled each other through the narrow, winding streets and over the nine bridges spanning the two channels of the River Lee.

The city leaders had been wrestling with the problem of too many river channels and too few bridges for centuries. A main channel had been covered over in the 18th century to create Patrick Street. Many of the other main streets, such as South Mall, remained wharves until after 1800.

As the horse and cart gave way to the motor car, new problems arose.

In August, 1937, Mr D.G. McNamara proposed “the Corporation consider the culverting of part of the South Channel, so as to have an area for car parking, etc: the finance to come from the Department of Public Works as a relief grant for the unemployed of Cork.”

Fortunately, all-powerful city manager Philip Monahan ignored his request.

However, by the early 1960s, 11,000 cars were driving through the city every day and estimates suggested this would reach a staggering 54,000 by 1968. Few people wanted to be there, but they could not cross the city otherwise.

In July, 1963, the Corporation advertised for a traffic consultant to survey and present plans for parking, road improvements and traffic control measures to solve the chronic problems. They appointed Patrick F. McCarthy, of B.K.S Consultative Technical Services, based in Raheny, Dublin. As a short-term measure, in 1965, B.K.S recommended a one-way system that never saw light of day.

Matters finally came to a head with the permanent closure of Parnell Bridge due to metal fatigue on January 19, 1968, which led to monumental congestion, as I recall from that day as a boy. To end the gridlock, a remarkable solution was proposed.

The plan

On March 19, 1968, the Echo reported that B.K.S had finally submitted its traffic plan to Cork Corporation. It was dramatic, radical, and eye-wateringly expensive.

To get traffic moving freely through the city, vast areas would be demolished. The plan envisaged new bridges and ring roads, widened arterial and city centre roads, and suburban one-way traffic systems. The completion date was 1986.

The stand-out feature was an incredibly ambitious and landscape-changing, partly-elevated three-lane motorway, 30 metres (100ft) wide circling the city centre, which would siphon traffic in and out.

This two-and-a-half mile road would cost £6.65million alone, and run from a ground-level roundabout at a junction of the airport road and Boreenmanna Road, across Rutland Street, Travers Street, Barrack Street, Washington Street, North Main Street, John Redmond Street, and Wellington Road, to the original roundabout at the Boreenmanna Road junction.

Huge multi-storey car parks would form a ring around the centre and new footbridges would allow pedestrians cross from these into the centre.

The consultants urged that land and property acquisition begin immediately, financed by higher rates and Government grants.

The cost of land acquisition for the roads was £2.1million (£1million for the property alone) and £13.5million for road construction. The state’s entire transport budget in 1968 was £13.7million.

The reaction

Despite heroic work by Irish Times journalist Mary Leland - who described the plan as “the sprawling octopus of an elevated highway” which would “wrap the city in a ring of concrete” - public reaction was at first muted.

There were few copies of the 153-page report in circulation. Objectors had to write to the Planning Office in City Hall to access them. Even today, the only full publicly available copy of the report is in the National Library.

British architect Brian Sidnell was scathing about the elevated motorway aspect of the plan. It would destroy the character of the city, he said. It is not hard to see how he reached that conclusion.

Ground-zero for destruction were the houses of The Marsh, Cork’s oldest neighbourhood, where more than 1,000 mostly elderly and working class people lived.

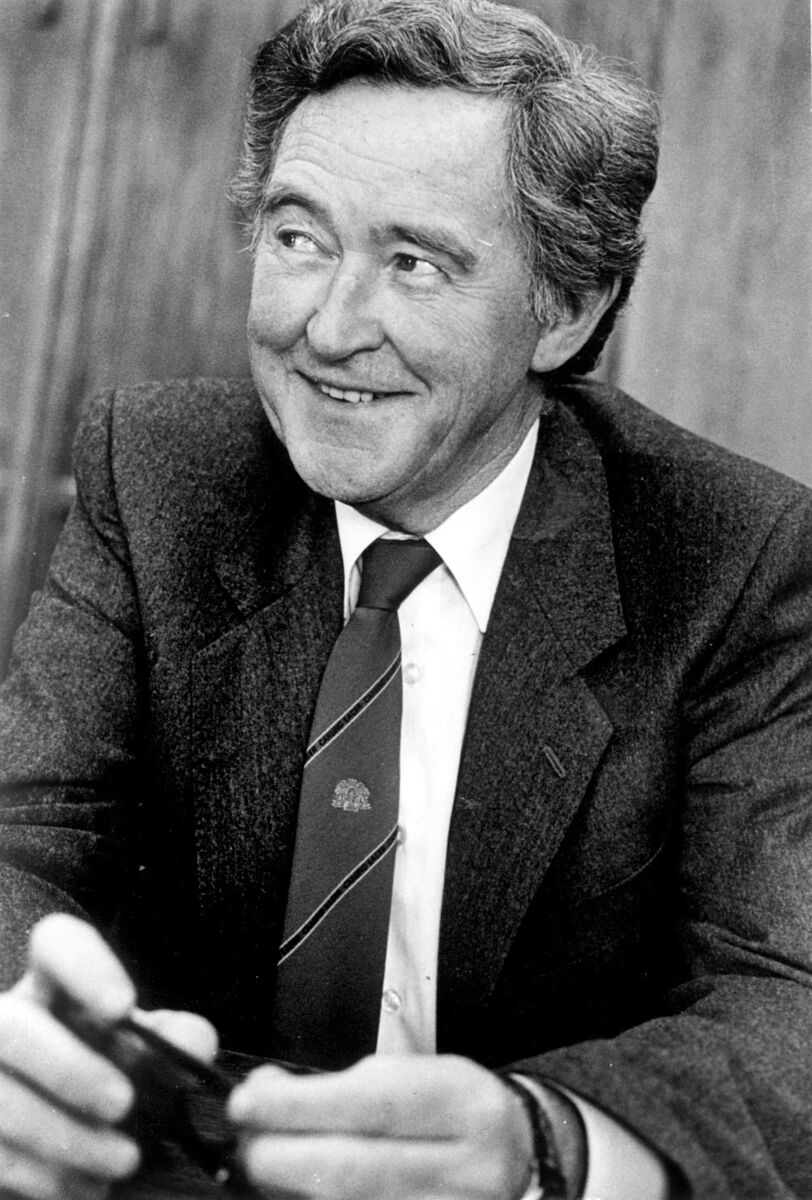

The people there demanded to meet councillors and the Lord Mayor, Peter Barry, TD, in the Middle Parish Hall. At a time of great deference to authority, this was practically unheard of.

At the meeting, Cllr Barry made it clear he for one was not convinced the plan was good for Cork. At a subsequent meeting in the teachers’ club, students and staff from UCC and the College of Art shredded it.

When the city engineer was asked about those living under the road, he replied “they will get used to it”. The meeting ended in uproar and threats of legal action.

An Foras Forbartha - the National Institute for Physical Planning and Construction Research - dealt another blow to the plan by commissioning Peter Dovell, Professor of Urban Design at Manchester University, to examine it. In June, 1971, his report was scathing of the damage it would do to the fabric of the city.

“Every decision to clear an area or demolish any part of the inner city needs the most critical assessment to ensure nothing is lost of significance,” Prof Dovell urged. “Once cleared, there is no time for second thoughts and Cork is particularly vulnerable. It is a city with a certain fragile dignity that should be respected and fought for, by all who value its heritage. In a hierarchy of cities, Cork is special.”

Even the most ardent supporter of the plan would have found it hard to disagree that Cork was indeed special!

Mounting opposition forced councillors into a series of defensive reviews and reassessments, including an expensive, £16,500 fact-finding trip to English cities by an eight-man delegation of councillors and officials. There is no record of their findings, but the Corpo wasn’t for turning.

Fifty-one years ago, on March 28, 1973, the Corporation voted 15-1 to proceed with the plan. The sole dissenting voice was the blind Labour councillor Pearse Leahy - who became Lord Mayor of Cork in 1969 - and who was arguably being more far-sighted than his colleagues.

Lord Mayor Seán O’Leary was ecstatic, declaring: “Anybody with plans to develop property in the centre of Cork city need have no more inhibitions now that the Corporation has decided on a positive, long-term traffic plan.”

He added that the proposal “should be used to develop the city on a planned basis, at minimum cost to the ratepayers”.

The plan dies

It took seven months for the entire financial foundations of the plan to collapse - and it took a global financial crisis

In October, 1973, oil prices rocketed with the start of the Arab-Israeli war and Ireland plunged into recession. Any chance of prising money out of national government went with it.

In 1974, a new city manager, Joe McHugh, brought a new emphasis on preserving and upgrading the built heritage, developing the Huguenot quarter off Patrick Street, rebuilding the North Main Street area of old Cork and - after a fire there in 1980 - fully restoring the English Market.

These developments were critical as they had all been slated for demolition under the B.K.S proposal and suffered from urban blight as a result.

Mr McHugh oversaw the restoration of Christ Church, and the creation of Bishop Lucey Park. Most importantly, he initiated a regional Land-Use and Transportation Study, which created a ring-road to divert traffic around the city and cross the river via the Jack Lynch Tunnel.

And so, Cork, ‘the beautiful city’, was saved from the all-conquering car and the close-knit community in the heart of the city survived to live another day.

ROUTE OF ELEVATED MOTORWAY

The elevated motorway would have passed along Wellington Road (one side at least having to be demolished), cut across Patrick’s Hill, and over Leitrim Street to Shandon Hill.

Turning south, it passed close behind St Mary’s, Pope’s Quay, and across the river at high level. It cut through North Main Street to Grattan Street, with demolition on the western side, and passed close to St Francis’ Church and the Courthouse.

From here, it would cross the South Channel before turning east in front of St Finbarre’s and entering a cutting along Douglas Street, then turning north to reach the old Cork-Bandon Railway.

Once more, it crossed the two channels of the river to re-join the Wellington Road section, with a complex multi-level interchange junction encircling both St Patrick’s and Trinity Presbyterian Church.

Under the plans, the two rail bridges in the city - the Clontarf and Brian Boru bridges - would be replaced by 1980. The Parnell and South Gate bridges would be removed and widened to four lanes. A relief bridge at Cornmarket Street would divert through traffic around the city.