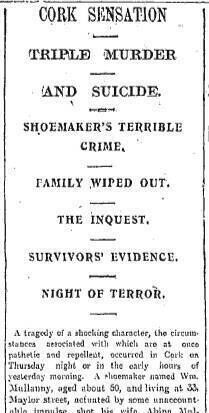

The massacre that Cork forgot: Four dead in bloodbath on Maylor Street

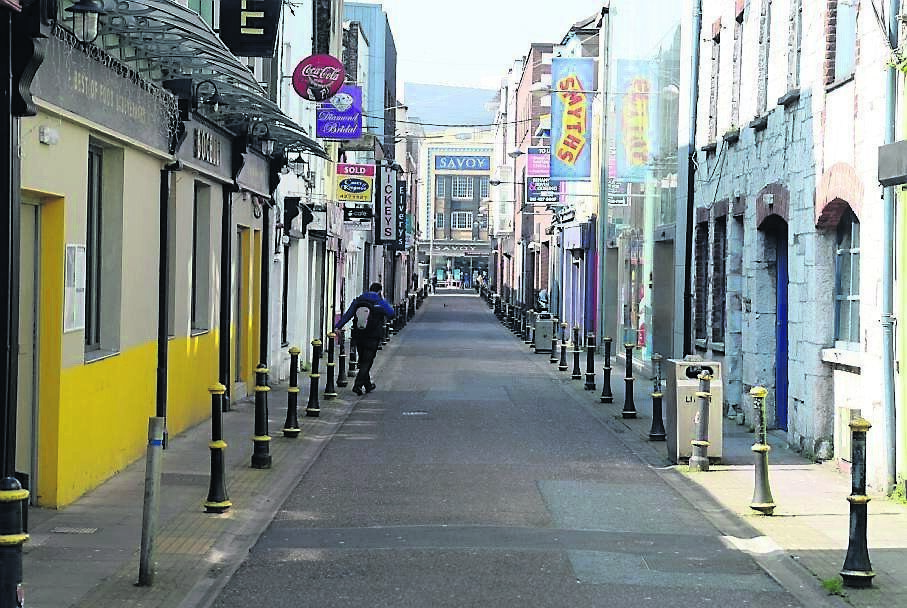

Patrick Street in the early 2Oth century. The 1914 murders happened in Maylor Street, just off Pana

IN the annals of Cork history, few events have been so unspeakably horrific, so gut-wrenchingly tragic, that the city and its people simply wipe it from their collective memory.

Having drunk it, he noticed Dina talking to Bridget under the bed, so she decided to come out. She asked her father if he was going to shoot her. “No,” he said, “I want you to take care of them. You are my daughter. The others are not.” He then went into his bedroom and shot himself.

The coroner asked Bridget if she ever saw a revolver in the house and she told him three or four years earlier, while her father was on an excursion, she burst open a drawer in the outhouse and saw it. He also had at one time a double-barrel shotgun. He threatened them several times.

Bridget said people used to say her father was mad, but she could not see anything wrong with him.

The next witness, John, 17, stated he was in bed when his father came home. He shared his bed with his little brother Paul and his father had also been sleeping with them of late. When William came home that night, John was reading in bed and his brother was asleep next to him. His father put the light out and went downstairs.

“He went to the next bedroom and shot Lizzie,” added John. “She was screeching and roaring that she was shot, and I said to my father ‘Shoot her and put her out of pain’.” He said: ‘No, she will die in a few minutes’.” John’s father told him to go to bed and get some sleep, then brought up a letter, telling him “not to give it to anyone but my aunt”.

The envelope, produced in court, contained a note stating ‘A brother’s request to a sister’ along with three receipts in connection with burials of members of his family in St Joseph’s Cemetery.

John went into heart-breaking detail about how he had helped saved Lizzie. His father went into her room and said he was going to shoot her again, but her pleading seemed to have an effect and William hesitated; John pleaded with his father not to shoot Lizzie, he agreed and left the room.

John said his parents did not get on and confirmed his father had a revolver.

William’s sister, Mrs Rose Cahill, was the final witness and said she did not think he was right in his mind for some time. “He used to talk at random, and one could not rightly understand what he was saying.” She did not know him to utter threats to his family, but on Sunday night he told her he was going away to France. She believed he would as he and his wife were living unhappily for a number of years.

The funerals took place amid heart-breaking scenes. The eldest child, Kate, went against her father’s last wishes and interred her mother and siblings in her husband’s Lingwood family plot in St Joseph’s cemetery on Tory Top Road. The large crowd were testament to the high regard in which Abina was held.

The next day, in a much quieter ceremony, William was interred in the cemetery a few hundred yards from his wife and children. None of the surviving children attended.

POSTSCRIPT Bridget married James Neary, a soldier in the Connaught Rangers stationed in Crosshaven. They later relocated to Wales and had four children, one of whom emigrated to California. Bridget died in the U.S state in December, 1964.

Christina moved to Wales with Bridget and there met her husband Walter Webb, the son of a miner. They wed in 1929 and raised a family in Bedwellty. She died in London in 1992, aged 84.

Walter had some sort of breakdown after the tragedy and was discharged from the Royal Navy but seemed to get his life back together, found work with British Rail, married, and raised a family. He died in London in January, 1967.

Lizzie recovered from her wounds and went to work in the UK, but eventually returned to Cork where she died in July, 1978. She was buried in the Lingwood plot with her mother and siblings.

John moved to New York within six months of the massacre. He took up art as a therapeutic tool and sent some of his paintings to an old neighbour in Maylor Street, Michael Malloy - who had been on the inquest jury and befriended John after the tragedy. John died in 1960, aged 63.

As for the house at 33, Maylor Street, it was demolished when the Merchant’s Quay complex was built in the 1990s and nothing remains to remind us of the terrible tragedy that occurred there in September, 1914.