Documentary revisits famous boxing match in Cork, Chris Eubank Vs Steve Collins

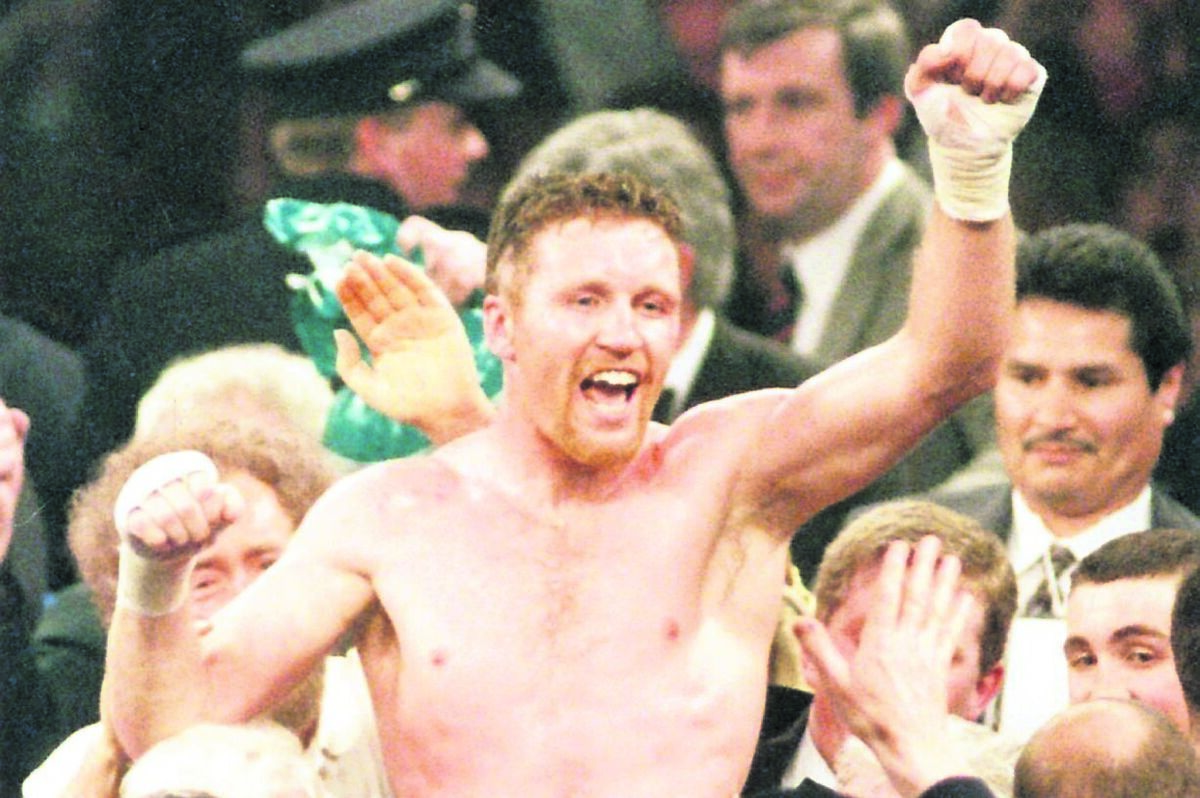

Steve Collins lands a left on Chris Eubank’s chin during their WBO World Super-Middleweight bout in Millstreet, County Cork, 1995.

ON March 18, 1995, the Green Glens Arena in Millstreet roared with the cheering of 8,000 boxing fans as Ireland’s Steve Collins squared off against Chris Eubank, the WBO Super Middleweight Champion of the World.

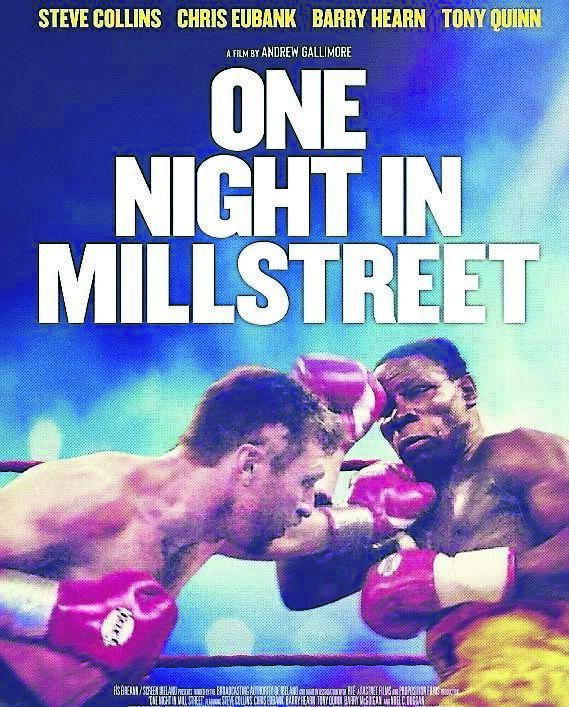

A new documentary, One Night In Millstreet, charts the journey to the ring and examines how a quiet Cork town became the location for one of boxing’s biggest nights.

The documentary’s director, Andrew Gallimore, was a reporter at the time of the fight and travelled to Cork by ferry from his home in Wales to cover the epic showdown. Like many people, he was surprised to find himself so far away from the city.

“I thought it was mad. Everybody did. I shared a taxi with two guys with press passes like me. We were naive, thinking Millstreet was only 10 minutes away from the city. When we finally got to Green Glens, you realised that this is a big complex with the requisite infrastructure to stage a world title fight, but when you go through the village, you think this cannot possibly be it.”

Two years earlier, the owner of Green Glens, Noel C Duggan, pulled off a massive coup by hosting the Eurovision Song Contest at the venue. His second coup was to convince boxing promoter Barry Hearn, to bring his fight to Millstreet.

Duggan and Hearn contributed to the documentary, as did sports reporters, including Paul Howard. Like Duggan, Gallimore also pulled off a coup by getting Collins and Eubank to participate in the documentary.

“The cliche about history always written by the winners could be said about sports documentaries.

Getting the victors to contribute is generally straightforward; the real difficulty is getting somebody who lost to talk about their defeat. It was amazing that Eubank agreed to do it.

Gallimore says that undefeated gives boxers an edge and that many others would be unwilling to discuss their defeat.

“Part of Eubank’s whole persona was the fact that he was undefeated. Your undefeated record helps sell tickets, but in a sport as primal as boxing, it goes deeper. If you go into the ring knowing you’ve never been beaten, that must give you something that somebody who has tasted defeat doesn’t have.

“I wasn’t sure if Chris would agree to do it, but we got him at a reflective time in his career, and he is a spectacular interviewee.”

If getting Eubank on board was a coup, getting Tony Quinn to take part was a marvel, says Gallimore. The elusive businessperson and mind coach became Collins’ coach despite never having trained a boxer. He is a controversial figure and media-shy, and Gallimore was shocked when he agreed to speak on camera.

“If I was surprised we managed to get Chris Eubank on board, I was shocked that Tony Quinn agreed. He’s such an interesting character, and he polarises opinions. The screenings so far have been interesting. In Cork (during the Cork International Film Festiva)], we had a real boxing audience; it felt like we were at a fight, not a festival screening. The constant, whether it’s been a film festival audience or more of a traditional boxing audience, has been the appearance of Tony Quinn devotees. We’ve never met anybody who’s neutral about Tony. You’re either in his camp or you’re not.”

The director says Quinn’s contribution was vital in the context of the fight, but it was not the right time to examine him in depth.

“The key for us was to use him completely in context. We gave enough background information so that an audience who didn’t know him could get a good idea of who he was.

We couldn’t go into all the issues because this is about Millstreet and the fight. There are other documentaries to be made about him; this was not the time.

When it came to finding footage of the fight, Gallimore says he was spoilt for choice.

“We knew there would be plenty of footage of the press conferences and fights, but the archive exceeded expectations. Steve Collins had a box of VHS cassettes with extraordinary footage of himself and Tony Quinn in Las Vegas. One of the producers found a guy who was a huge fan of Eubank and had so much footage. Millstreet documented all the Eurovision and the build-up to the fight, which was fantastic. We could cut between the official Sky Sports footage and footage of local people and Millstreet.

We had an embarrassment of visual material to work with.

Although this is an Irish story, it has universal appeal, which Gallimore says is due to its underdog nature.

“On one level, it is a quintessentially Irish story, but the underdog story is universal. It’s something everybody can relate to. You don’t have to be Irish or come from Cork to connect with it..”

The filmmaker was also aware he wanted this to appeal to boxing fans and non-followers of the sport.

“We couldn’t dumb it down to the point where we lost our boxing audience, but we didn’t want to alienate non-boxing people either.

“The two lead protagonists are such interesting characters, and we tried to make it in such a way that the audience cared about what happened to the two of them.

It didn’t matter whether they were playing tennis or were part of a sports team; you cared about the outcome because you cared about them.

Gallimore hopes audiences will feel uplifted by watching the film. “It’s one of those rare stories which gave us the opportunity to make people laugh. There are some sad moments, but at the end of the day, this event happened against all the odds. All these people have lived to tell the tale, and, somehow, they have all got some resolution out of it.”

He also has a special message for Cork: “It was so great to have its world premiere in Cork at the festival. As well as capturing the personalities, I hope we’ve captured a little bit of Cork as well.”

One Night In Millstreet opens in cinemas on April 5.

See our review below.