Something in the water: how Kaught at the Kampus still influences young Cork musicians over 40 years on

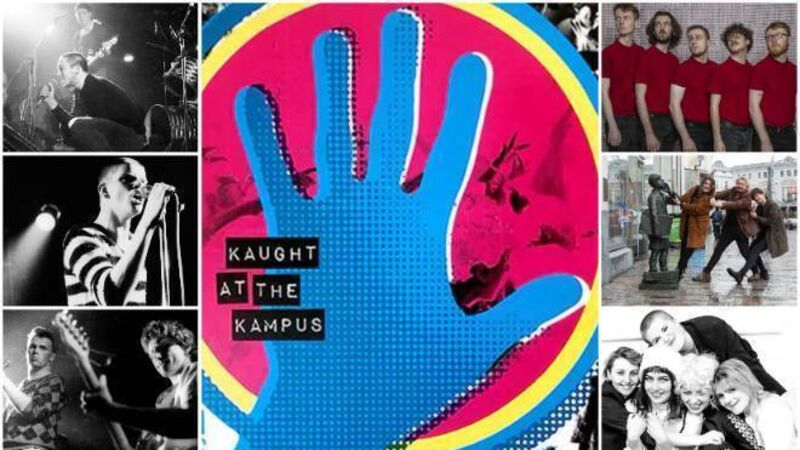

Left, top to bottom: Mean Features, Finbar Donnelly of Nun Attax, Micro-Disney. Right, top to bottom: God Alone, Pretty Happy, I Dreamed I Dream

On August 30, 1980, a smattering of bands from Cork’s then-emergent post-punk scene, including Nun Attax, Micro-Disney, Mean Features and Urban Blitz, piled into the Downtown Kampus, also known as the Arcadia Ballroom on Lower Glanmire Road, for a special showcase gig - ploughing headlong into displays of the spiky, discordant and utterly atypical noisemaking that would in time become recognisable as part of a distinct Leeside sound.

On hand was a mobile studio that was borrowed from Belfast connections of promoter Elvera Butler, which, while hyped up as having been used to record tracks for the Rolling Stones, amounted to little more than a caravan with a mixing desk - but on that night, a shortage of tape notwithstanding, it was more than enough to capture history in the making. What was simply meant to be a showpiece to be sent to the radio and press of the time was released on 12” vinyl the following year as ‘Kaught at the Kampus’, the first release on Butler’s Reekus Records label.

The four decades that have unfurled since has seen life come and go - Nun Attax would morph into Five Go Down to the Sea? and later Beethoven, before the tragic early passing of frontman Finbar Donnelly in 1989; Mean Features frontman Mick Lynch would go on to find cult success as part of Cork/London outfit Stump, whose 2015 reunion was upended by Lynch’s sudden passing that December; while Micro-Disney would drop the hyphen and go on to take on the world, before frontman Cathal Coughlan would plough a longer furrow as part of The Fatima Mansions, with solo projects, and later Telefís, before the announcement of his passing in May of 2022.

Life has come and gone for the broader alternative Cork scene the bands helped lay the foundation for, too, and the legend of Kaught at the Kampus has grown accordingly, with dedicated gig-goers, friends, peers and family all keeping the flame lit over the years, and periodic revivals & remembrances such as Paul McDermott’s outstanding audio documentaries serving as powerful reminders of the idiosyncratic power of Leeside post-punk of the 1980s - distinctly working-class, spat out in Northside accents and possessed of a dry, eclectic humour.

And in that warmth and crooked reverie, something curious has happened - its influence, having taken root and indirectly made itself apparent as the years wore on, has come to the forefront for a wave of young music-makers, who, a generation later, also find themselves staring recession in the face, out of the attentions of broader music-business pressures, and with full awareness of the precedent the record and its descendants has set, empowered to follow their creative impulses.

“We'd know the names,” says Arran Blake, bassist/vocalist of Mayfield noise-rock trio Pretty Happy, whose collective documentary film, ‘ Leeside Creatures’, observes the legacy of the ‘80s Leeside post-punk scene in a modern context. “We've known Finbar Donnelly, because our Mam lived in the Glen, and y'know, she knew the Donnellys - they were only over the road from each other.” “It was very vague, though, it was what you'd hear Mam and Dad talking about”, adds Pretty Happy guitarist and vocalist Abbey Blake. “Our Mam talked about Finbar Donnelly, but it was in the same vein as other old neighbours and stuff. It was never this big superstar, unbelievable guy. It was like, 'oh, yeah, Finbar, he was mad'.”

“I found Nun Attax on YouTube, when I was thirteen, because I looked up ‘Cork punk’,” says Cian Mullane, bassist/vocalist in genre-melding rock outfit God Alone, and a proud Norrie. “I'd found (2000s black-metallers) Altar of Plagues on (online metal resource) Encyclopedia Metallum, and I was like, 'that's cool, are there any other lads from Cork?'. I saw them, and I thought, this is cool, these lads look mad. I didn't realise they were from the Northside, these are lads who were around when my dad was around, that were, like, making tunes, and they're all from Farranree or Gurranabraher, and Mayfield, I was like 'that's cool'. I would have [sought out] Kaught at the Kampus a few years after.”

“So my dad's cousin, Pat [Kelleher], played the bass in Mean Features,” says Elle O’Leary Kelleher, vocalist and guitarist from Cork art-punk scamps I Dreamed I Dream. “I was thirteen or fourteen when I started kind-of getting interested in punk music, and my dad would just be like, 'oh, Pat was in this punk band', and all this kind of stuff, but we were never able to actually find any... there was nothing on YouTube or anything like that at the time about it.

“Just by chance, we were driving somewhere one time and the radio documentary, [Paul McDermott’s Finbar Donnelly documentary] 'Get That Monster Off The Stage', just happened to be on. And my dad was like, 'oh, that's Pat's band!'. I was just... I couldn't believe it, it was just some fellas from Cork making music - I hadn't heard anything like it before. I mean, it didn't sound like any punk I was familiar with, and it just sounded so cool. It was a few years after that that I was able to track down [the Kaught at the Kampus record online].”

Julie Landers, drummer for I Dreamed I Dream, says: “I first came across Kaught at the Kampus in 2020, when they put the murals up on Grand Parade. I would have heard of Nun Attax before that, but I'm very much a blow-in. So, my knowledge of it would have come from looking from the outside - 'what is happening here, what is the scene, what's going on?'.

“Through going to things, and having conversations with people, I was learning about these other bands, like Microdisney. The conversations themselves were almost, like, looking back to look forward. It's something I'm trying to think of a lot more recently in my own artistic practice, like, 'how can you look back, and kind-of pay tribute to things without being doggedly fastidious in looking backwards?'. I think sometimes that can hinder art, more than it can help it.”

That process of looking back, listening to the record to the first time via online platforms and various explorations of its legacy, and learning about the circumstances that surrounded it, was, for many of the young artists interviewed, a matter of making contact with something familiar, both in terms of punk-rock intent and execution, and something completely out of the ordinary for a generation reared on broader musical geopolitics - a historic context for weird and identifiably Leeside sounds, delivered in entirely idiosyncratic fashion, right down to the accent.

“It wasn't really the music, per se, it was more like, I think for me personally, as a musician, it was the first time I’d heard of a group of young people [of that generation], playing music that had no connection to... whether it was something that was happening in Britain, or America, there was just none of this, mimicking what popular music was, the direction it was going, or anything like that, says Pretty Happy drummer Andy Killian.

“There's almost an 'American dream' within music, for a lot of people, that's why they play music, is to have this stardom and stuff, but there's just the absence of that, like, there's no ego. It's not that it's about Cork, it's that it's not about somewhere else. So naturally you end up using your colloquial [language], and I think like, I think maybe that's the thing that people see in us.”

“It was a slow lightbulb for me - Nun Attax, Five Go Down to the Sea? - they're one of my favourite bands,” says God Alone guitarist Jake O’Driscoll, who discovered the band via 2020 compilation ‘ Hiding from the Landlord’. released via Dublin's All City Records. “I think they're fantastic, but what was very good to hear, live on that album, is there's a certain kind of... absurdism with their music, that I identify with when we write stuff for God Alone, where it's a bit silly, but it's really good - it's kind of a Cork thing. A lot of people from Cork, when they talk to you, especially my parents and like grandparents, they kind-of sound like they're taking the p*ss out of ya. There is a bit of that on it, where it's punk, but it's not, like, angry and edgy.”

"It's gas hearing the lads at the start, like the Mean Features song where he's on about, 'this is a song about going on holidays with your mother and father' ('Summer Holiday'), or the Microdisney one where [Cathal Coughlan] is on about an aul' fella that smells like p*ss. That's class, like,” chuckles Cian in agreement. “It's like, you can read into it and be like, 'oh, that's a commentary on whatever', but I guarantee those lads were just in the practice space going, this is f**king funny. I think we do that as well, we like having a laugh."

"When you hear the bands that were on this record, y'know, number one, the Cork accent is just ringing through, but it's so weird that you're like, 'holy s**t, people from our town wrote this kind of music',” says Arran. “They're not trying to mimic anyone, it's just f**king bonkers - it's not people who go on stage to be cool, or to look sexy."

“Yeah, the lack of ego, there's no break for a big, self-indulgent guitar solo here, where we all have to look at the guitarist for ten minutes playing a manky scale that we've seen done a hundred times,” enthuses Abbey. “It's like, [Nun Attax guitarist] Ricky Dineen is going to dig his guitar, because he thinks it sounds funny. Like, that's so cool, I think, to break away from every boring b*stard who wants to play music. And it's so much cooler that it came from Cork.”

“You do feel a sense, or I did feel kind-of a sense of pride and identification with the fact that like, they were from Cork, they were doing this”, Elle says. “When I was listening to it for the first time online, I was too young to be going to gigs and stuff, I wasn't really aware of what was happening. So hearing that, going wow, those guys were doing this music and cultivating this scene, and they were just here, the same as me, not really following any kind of rulebook, I just thought that was really, really cool.”

“Having revisited the album an awful lot, you get a sense nearly of... permission to be completely off the wall, and weird. 'These guys were doing this, like in the late '70s, early '80s - of course, I can do it now.' You get a great sense of permission off it.”

That sense of distinctly Corkonian humour and experimentalism put down roots from the bands that played on and emerged from Kaught at the Kampus, as well as the crowds that remembered them, and into fertile creative soil as the years wore on.

The ‘Cork-chester’ hype machine that accompanied the smirk and gregariousness of the Sultans of Ping, and the sunny disposition of the Frank and Walters over a decade after the compilation’s release gave way to the ‘Ten By Ten’ bands of the mid-90s; aughties outfits like Rest, Waiting Room, Hope is Noise and Kerry blow-ins Ten Past Seven set the stage for psychedelia-inflected explorations of the post-crash generation, exemplified in the likes of The Altered Hours’ wiry post-punk and Fixity’s anti-pigeonholing splendour - and even the Cork-centric weirdness of rappers and beatmakers like Craic Boi Mental.

It’s not always been a matter of direct influence, so much as a sense of a different atmosphere, but for these young artists, the intangible throughline from the strangeness that emerged from the city forty years ago to the current sonic landscape, is apparent.

“It wasn't until we started playing, when people came up to us and said 'I know who ye must take influence from', and it was Stump, Microdisney and Nun Attax,” says Arran. At that point, we hadn't done the deep dive, but that's how we found out about it. I remember talking to Giordaí Ua Laoighre, during the making of our documentary, and he was part of Nun Attax, Microdisney and Nine Wassies from Bainne. He listened to our [Pretty Happy] song 'Salami', and when we actually met up again, he was in disbelief, he was like, 'ah, no, ye're messing... ye knew about all of this, surely.'”

“Knowing that there's like... maybe not so much a lineage as kind-of a foundation there, within Cork, for this kind of music is just really, really cool,” Julie says. “I definitely would have gotten more into it through hanging out with [my bandmates, and they're like] 'I have this really weird idea', and I like just being able to follow that. It'd be really weird not to explore those ideas for fear of how they sound, or for fear of how people will receive them. I think it's like, 'f**k it, we're going to try this and see how it goes', and the most spontaneous of bits have become our favorite things to play.”

“I have big time and respect for how Nun Attax used such a bold, janky bass, I've always really liked that a lot,” says I Dreamed I Dream bassist/vocalist Claire Aherne. “It made me realize that the bass doesn't have to be in the background as an instrument, it can be completely doing its own thing, so I really respected that. That's always something that stuck out for me. To have [a tune like Nun Attax' Reekus Sunfare] that's so janky, and so pop, almost something upbeat, but then for the lyrics to completely counteract that. I think that's class, and I suppose other artists have done that, but it's just there's something very Cork about it.”

“When I'm asked about guitar, I'm like, ‘I never learned scales’,” explains Abbey. “Me, myself, I find them boring to play, and I'd make myself cringe if I were to play a scale. I was talking to Ricky Dineen, and he basically was saying, 'ah, I'd be disgraced to go on stage looking cool, and playing cool scales’. He was the first person that I didn't say that to, and he just said it, and I was like, 'that's my line' (laughs).

"That's a Cork mentality right there - it's a personality thing. How could you follow what they're doing? It's so weird that you couldn't possibly go, 'I'm gonna sound like them'. You can't, they're just so strange. There's no formula, it is just absolute, like head-the-balls, playing music.”

More so than a generation of gig-goers and musicians simply placing pins on simpler times in their lives, or entertaining the idea of some sort of golden age, the ongoing legacy of Kaught at the Kampus - now available again on vinyl via Reekus Records in an expanded edition - is one of cultural documentation, capturing a critical moment in the development of music in the city, as bands who had to make it up as they went along were, quite literally, caught in the process of doing so.

That aforementioned throughline of independently-minded music and culture that’s shared in the atmosphere that the compilation has helped to foster in the four decades that followed now forms the basis of a wider sense of identity and belonging in the city among its young noisemakers, who, amid the aforementioned revivals and reunions, have been made aware of the cultural context and timeline in which their music and practice exists.

“[Kaught at the Kampus] for me totally signifies care, for music, and your city, it wouldn't be here without Elvera Butler,” says Abbey, in tribute to the compilation’s producer. “We can talk all day about those bands and they're unbelievable bands, but every time you talk to one of them, they will not fail to mention Elvera Butler. For a young woman, to be in college, found the college society to create a scene, to get the Arcadia, and help young bands like that, that was so important. And then to document it as well?

“It's just insane that it was down to one person, and it usually is down to one person who cares, but to care enough about music, and your city... to give opportunities to these bands like when they shouldn't have lasted, it was a poor city at the time. Elvera gave them opportunities to support these bigger bands [like U2 and UB40]. Like, that's huge for young bands. You learn so much supporting bigger bands, and for it to be down to one person, that is true care for your city. That's what we need for this next generation of bands.”

Says Elle: “I suppose it's always comforting to know that you're not working in isolation, isn't it? It's such a cool thing, that we have concrete evidence that this period happened, going back to myself, and literally coming on this entire scene, by pure chance, happening to hear a documentary on the radio.

“It's so cool that we've had the mural in town, the Pretty Happy lads made that unbelievable documentary, and the fact that we have the repress of the album, that it's so easy now for kids in Cork to have an interest in the history of their city and the music in it, to be able to access that so easily, and really see where everything that's happening now has come from. We always know that nothing exists in a vacuum, but being able to, like, trace the roots as such, they do a family tree, nearly, of Cork music, that's so nice.”

Opines Julie on that ‘something-in-the-water’ factor: “The lore behind it has definitely informed this knowledge that this is, like, Cork, but then you're also hearing this really weird s**t going on with it, that I've heard in other Cork bands' works since then. Cork is just a place where weird stuff brews.

“I've said to friends before, and it's a really offensive thing to say, but Cork, geographically and anthropologically, shouldn't exist. It's a bowl, next to a river on a marsh. But the Cork people are so f**king tenacious, like, 'nah, we're gonna make this work, and we're gonna make it the best place ever.' And, like, you have to be a bit tapped for that, I think (laughs).”

“I feel like there's very big boots to fill. Some people have been filling the boots with their hands, and I feel like we've been filling those boots with a half sliced pan, but we're filling the boots nonetheless,” says Claire. “I don't think that weirdness is ever going to be something we can part with, whether we want to or not, I think we're always just going to be making weird-ass tunes. I think that's a great thing, I think we've got to own it.

“I don't think we'll ever really fit into one box or one genre, I think. Yeah, we might start singing a sean-nós tune, and then yeah, we might spend ten minutes playing absolute noise and getting feedback from a guitar amp into, like, six different distortion pedals, but that's the art of it, and that's the craic of it and they're the boots we're going to fill.”

- Kaught at the Kampus’ 40th anniversary LP edition, including bonus RTÉ session and studio material from the period, a zine with essays from a range of Cork music heads, and a CD of material from current-day project Big Boy Foolish, is available in Bunker Vinyl and MusicZone now, or via mail-order directly from Reekus Records’ Elvera Butler: info@reekusrecords.com.