Kathriona Devereux: A simple blood test could be key to winning war on cancer

About 42,000 people in Ireland develop cancer each year, and the Galleri test is a possible game-changer when it comes to catching and treating it early. Especially for deadlier cancers that have no recommended screening tests and poorer outcomes because of later detection.

It’s the kind of breakthrough that scientists have been working towards for decades, since President Richard Nixon declared a ‘war on cancer’.

In December, 1971, Nixon told the American public he was about to “launch an unprecedented attack”. Not against the Vietnamese or the Russians but against the leading cause of death in the U.S at the time - cancer.

For a change, this was a war that everyone could get behind.

In signing the National Cancer Act, Nixon committed hundreds of millions of dollars to cancer research and called for an “all-out assault on cancer”.

At the time, it was likened to an Apollo programme style effort for medical research.

Instead of the aim of reaching the moon, Nixon’s advisers believed that a focused national effort with a clear goal of conquering cancer would lead to a cure.

Some of the President’s advisers reportedly told him that a cure might be found within five years if resources were concentrated and bureaucratic obstacles removed, hence the military-esque language. Nixon pledged to “place the full weight of the Presidency behind the national cancer programme”.

But cancer wasn’t one enemy but many. Not a single disease, but a vast family of diseases with different genetic and biological causes.

The research boost did stimulate significant strides in the fields of chemotherapy, childhood leukaemia and Hodgkin Lymphoma, and the National Cancer Act had a long-lasting impact on the approaches to prevent, diagnose, study, treat and cure cancer.

But the fight against cancer continues. It is the main cause of death in Ireland, responsible for one third. More than 9,600 deaths from cancer are reported every year. There is barely a person in the country that hasn’t been affected by a devastating cancer diagnosis.

Sadly, the vast majority of people who die from cancer do so because doctors find it too late.

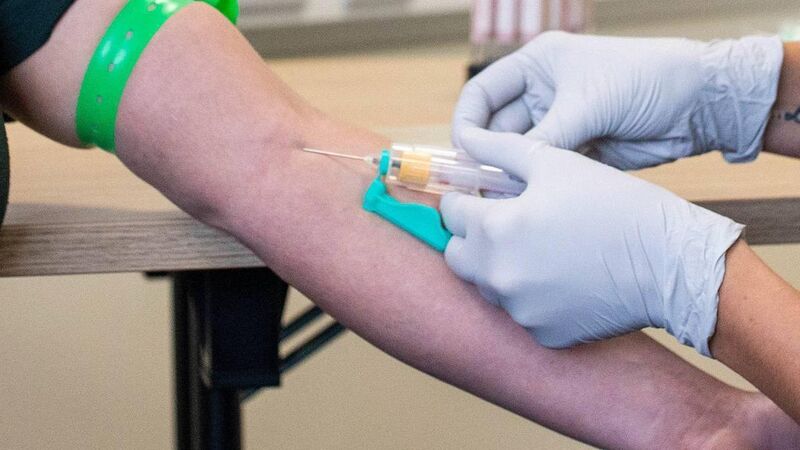

The Galleri test’s powerful ability to detect tiny fragments of cancerous DNA that are circulating in the blood could be a new type of early warning system and be revolutionary in cancer detection and diagnosis.

The test checks for DNA fragments from cancer cells that have detached from a tumour. When receiving results, patients are told if there is a “Cancer Signal Detected”.

The likelihood of receiving a cancer diagnosis following a positive test result was 61.6% in the latest study.

A key benefit of the test is its ability to predict where in the body the cancer is located. The DNA fragments act like a unique ‘fingerprint’, pointing to the cancer’s origin. Research shows that the blood test correctly identified the origin of the cancer in nine out of 10 cases.

However, the test doesn’t detect all cancers and problems of false positive and false negative test results exist.

Significantly, three-quarters of cancers detected were those which have no screening programme such as ovarian, liver, stomach, bladder and pancreatic cancer.

While still only trialled in the U.S and UK. and with no formal FDA or European regulatory approval, the excitement about this test is that it is such a potentially powerful tool for healthcare.

Doctors are eager to have a tool that helps with early detection, quick diagnoses and treating patients before they are even sick.

Still, as Nixon discovered, early optimism can outpace reality. Researchers are rightly cautious.

The big unknown is whether catching cancers through multi-cancer early detection tests reduces deaths or improves quality of life compared with standard routes.

Even a small false-positive rate could mean large numbers of people undergoing unnecessary scans, biopsies and anxiety - especially if rolled out on a population scale.

Cost is another factor. The test currently costs about $900-$1,000 in the U.S, which raises uncomfortable questions about who benefits from this breakthrough - the wealthy early adopters, or the people most at risk.

Implementing a multi-cancer blood test into public screening programmes would require significant policy change, pilot schemes, regulatory approval, and the infrastructure for follow-up diagnostics.

In the meantime, the Irish Cancer Society reminds us that around four in ten cancers can be prevented.

Smoking remains the single biggest cause - responsible for one in three cancers - while healthy eating, exercise, and limiting alcohol all make a real difference.

These are the battles we can all fight today, without waiting for the next technological leap.

When Nixon declared a war on cancer in 1971, he imagined a moonshot victory. A cure discovered, the disease defeated. Half a century later, we know cancer doesn’t surrender easily.

But every small advance, from precision medicine to blood tests like Galleri, moves us away from cancer’s “long shadow of fear” and replaces it with hope.

App?

App?