John Arnold: Yarn about yearning husband, pining for his sea goddess wife

I suppose any poem or song or story concerning a glen is special and unique, because a glen is usually an entity of its own with it’s own unique story to tell. So it is with Glenariff, one of the famed nine Glens of Antrim. Each of the nine is different and is named for different physical and historic features.

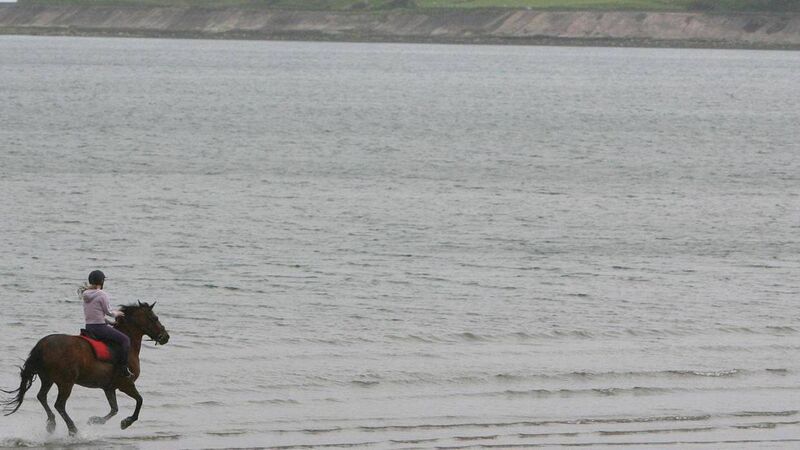

Gleann Aireamh is the glen of the arable land. Where Glenariff touches the coast nestles the little village of Waterfoot. To this day, fishermen ply their trade offshore here. Close to the shore is what looks like a stone arch -it was once the mouth of a cave, but thousands of years of pounding waves have eroded it and just the arch now remains. On the beach nearby is a huge flat flagstone. Every seven years a strange, melancholy sound can be heard here.

Many years ago, a young fisherman called Shawn was one of the two dozen or more who made a living from the bountiful harvest of the sea. His boat was crewed by himself and two others.

They trawled out nets, pots and lines to fish for lobster, pollock, and occasionally salmon. Depending on the plentifulness or otherwise of fish, the boats would venture maybe half a mile off shore in this sheltered part of the Antrim coast.

Fishing then was a way of living and if the waters yielded richly a fisherman could be comfortably well off. Shawn’s two helpers were ‘paid’ with fish to sell themselves and take home to their families.

If the weather was benign and the shoals were close to shore, a good living was to be made.

One morning, the three had rowed out into the bay and plied out their nets and lines. The time came, a few hours later, to pull in the nets and survey the contents. As they pulled, they felt a heavy weight under the water and smiled in anticipation of a large haul.

As they got the nets back in over the side of the boat, the saw to their horror a tangled, mangled mess of netting, and in the midst of it all a large bull seal flailing and thrashing. The seal had obviously been fishing too and got enmeshed in the fishermen’s nets.

Everything was bulled into the boat - nets, seal and a few fish. Shawn’s comrades took out their knives to kill the seal and make it easier to recover some of the torn nets. “No,” said Shawn as he looked at the big sad eyes of the captured animal. “He never did any harm to us so we won’t harm him.”

So the three men set to work with their knives and after about an hour or so they had the mammal free and returned to his watery home. In the boat were the ragged remains of what had been fine fishing nets. They made for shore with a meagre few fish.

Two days were spent with hemp, needles, awls and knotters repairing their nets before they returned to sea. On a beautiful day, they plied their trade once more. They were just started ‘drawing in’ when they were stunned.

Like in the Bible long ago, their boat was nearly sinking as they came ashore. “Look-out there,” shouted one of Shawn’s helpers, pointing seawards, and sure enough in their gaze they saw a big seal on the water - it looked like the seal they had released a few days ago!

So it went all that fishing season, massive hauls each day. Shawn was stunned. Each day he took baskets to the market and his helpers were well paid.

Unfortunately, with their new- found ‘wealth’, Conal and Paraig decided to emigrate and they went off to Scotland.

Mending his fishing gear one sunny day, Shawn saw a young woman coming towards him. A beautiful girl with long, flowing locks and sallow features. She enquired if he needed help with the fishing.

Tradition in that part of Antrim generally meant females were seldom if ever left on a boat - never mind to go out fishing. Beggars can’t be choosers however, Shawn thought, and so Namara, that was her name, went on that little fishing boat.

So they lived happily and he continued fishing with bountiful catches each day - and the seal was always around, as if watching over Shawn and his wife.

The couple had four boys born to them in the space of six years - strong, healthy children.

Then Shawn noticed Namara was changing. She was argumentative and inclined to bicker and give out to him - so different from their early years as a couple. One afternoon he came back from the village and the four boys were playing in the garden. They said their mother was gone down to the seashore.

Shawn went down and there he saw Namara standing, crying, on the big flagstone, with something on the ground by her side. “I must leave,” she said.

He was stunned. She picked up a seal skin from the sand. “I am Inion na Mara - the daughter of the sea - my father is the seal you saved and he sent me to reward you for your kindness in saving his life, but I can only stay on land for seven years - if I stay longer, I will die.”

She threw off her clothes there on the strand and pulled on the seal skin. Shawn tried to hold her, to stop her, but she just slid into the water as her father watched from the waves offshore.

Shawn swam out after her in a vain attempt to bring her back, but to no avail. Wailing and crying, he went back to his four little boys and tried to explain the unexplainable to them.

He fished on, as did his sons after him. Locals wondered why Shawn and his family always seemed to catch more fish than anyone in the district. Only Shawn and his sons knew the reason.

Every seven years, to this day, if you go down to that stone arch near Waterfoot, you’ll hear the sobbing and crying of Shawn as he still yearns for his Inion na Mara. Then, after a wee while, if you listen and the sea is calm you might hear;

App?

App?