Sinéad’s final wish: To stage an exhibition of her paintings

IT was kind of ironic that the second item on the RTÉ news last Wednesday evening was about a damning report highlighting the fact that the HSE’s child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) is woefully inadequate.

There is an “increasing risk to children for whom the service is provided,” according to consultant psychiatrist, Dr John Hillery, chair of the Mental Health Commission.

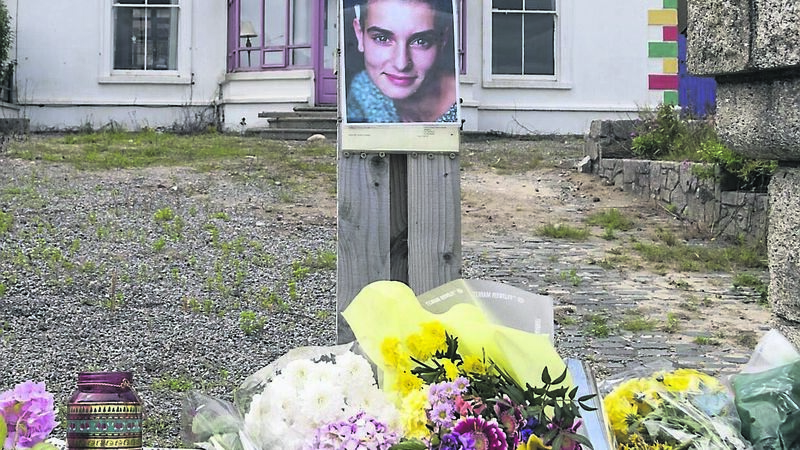

The lead story was the dreadful news that Sinéad O’Connor had died.

The talented, passionate but troubled singer’s heart was broken because of her son, Shane’s suicide at the age of 17 last year. He had allegedly been on suicide watch in a Dublin hospital but escaped and ended his life in the grip of mental illness.

The treatment of vulnerable young people in this country is sorely lacking. Chief mental health inspector, Dr Susan Finnerty, made damning comments about the service, saying it fails to manage risk and has failed to fund and recruit key staff. It also falls short of looking at “alternative models of providing services”.

Also last week, a 15-year-old boy affected by the care he received at South Kerry CAMHS had a settlement of €92,500 approved by the High Court. The HSE is facing hundreds of other claims alleging inadequate treatment from the service.

Children and adolescents (aged 18 and younger) constitute 24% of the population, yet CAMHS receives just 12% of the overall mental health budget.

And, unlike the adult mental health services, which are regulated under the Mental Health Act 2001, CAMHS is not regulated. In other words, young people are not treated with the care and respect that should be their right.

Because of the absence of regulation, there is no organisation that has the power to ensure that children’s rights are vindicated.

She moved there last month and wrote on social media of her hope and excitement at writing new songs, a few days before she died.

She came across as optimistic and humorous in a post a couple of weeks ago, declaring that ‘the bitch is back’. But the black dog was never too far away. Sinead admitted that she had been living as “an undead night creature” since her son’s death.

Having fought the black dog myself (well, not so much a battle fought, more a case of medication ingested), it’s impossible to believe that things will get better while you’re going through a deeply depressive period.

But if you get the right medication, it can help hugely.

The trade-off, though, is a flatness, an absence of emotion, a life lived at a certain remove. Still, it beats the sense of dread and fear that can accompany depression.

Reading Sinéad O’Connor’s autobiography, Rememberings, a chapter called Forward and Now is about her faith. She writes: “In Islam, we believe that in heaven it’s always night. I hope so. And I hope if there’s a heaven, I qualify (if there’s such a situation as not qualifying.) “I have a hard time believing God would be so cruel. But just in case I deserve otherwise, I hope the fact I’ve sung will make little of my sins, which are ugly and legion.”

Sinead added: “When I shuffle off this mortal coil, I want every person to whom I gave a painting to gather in one place and have an exhibition. These people have never met. They are from all walks of life. I’d like them to meet if they haven’t trashed the paintings. And even if they have.” Painting, she writes, is her way of praying. It’s another way of communicating. And Sinead was a great communicator, even if her message wasn’t always welcome.

No doubt, were she still alive, she’d have had something to say about the scandal of the CAMHS.

Thank-you for the music and for being the bolshiest public figure Ireland has ever had.

What a true legend. RIP.

App?

App?