Poetic side of Michael Collins offered a glimpse of his Ireland

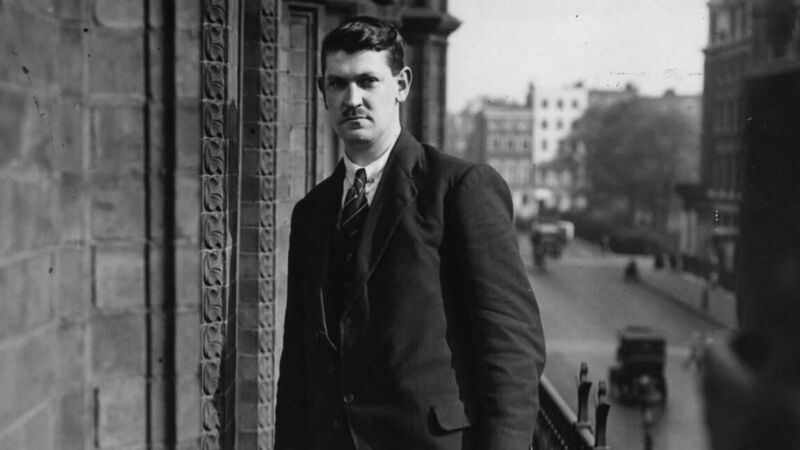

Michael Collins.

AS we mark the centenary of the death of Michael Collins on August 22, it is interesting to examine how he himself speculated on the future of the country before he died so prematurely.

In a series of speeches and articles, written in the period between the signing of the Treaty in 1921 and the outbreak of the Civil War the following year, Collins passionately defended the Treaty he and the other plenipotentiaries had signed in Downing Street.

He also speculated on what an independent Ireland might look and feel like.

But, in the first instance, it was where the essence of Irishness could be found that engaged him.

In one article, Collins concluded that the remnants of Gaelic civilisation could only be found at that stage “in the remote corners of Ireland in the South and West and North-West. It is only in those places that any native beauty and grace in Irish life survives. And these are the poorest parts of the country!”

Collins then lyrically evoked a rustic peasant life that obviously for him was a distillation of this Gaelic essence.

He wrote: “On the island of Achill, impoverished as the people are, hard as their lives are, difficult as the struggle for existence is, the outward aspect is a pageant. One may see processions of young women riding down on the island ponies to collect sand from the seashore, or gathering in the turf, dressed in their shawls and in their brilliantly coloured skirts made of material spun, woven and dyed by themselves, as it has been spun woven and dyed for over a thousand years.

“Their cottages are also little changed. They remain simple and picturesque. It is only in such places that one gets a glimpse of what Ireland may become again, when the beauty may be something more than a pageant, and will be the outward sign of a prosperous and happy Gaelic life.”

Such richly poetic language from the architect of the guerrilla war that brought the British regime in Ireland to its knees might surprise a lot of people.

A little over 20 years later in a radio address, on St Patrick’s Day 1943, then Taoiseach Éamon de Valera’s description of Ireland as a rural idyll would chime with the words of the man he was once a mentor to: “The ideal Ireland that we would have, the Ireland that we dreamed of, would be the home of a people who valued material wealth only as a basis for right living, of a people who, satisfied with frugal comfort, devoted their leisure to the things of the spirit - a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youths and the laughter of happy maidens, whose firesides would be forums for the wisdom of serene old age.”

This is the shared romanticism of two men whose falling out was a huge contributory factor to the Civil War.

But Michael Collins balanced his poetry with hard economics. In an article entitled ‘Building up Ireland’ he wrote: “If our national economy is put on a sound footing from the beginning it will, in the new Ireland, be possible for our people to provide themselves with the ordinary requirements of decent living.

“What we must aim at is the building up of a sound economic life in which great discrepancies cannot occur. We must not have the destitution of poverty at one end, and at the other an excess of riches in the possession of a few individuals, beyond what they can spend with satisfaction and justification.

“The growing wealth of Ireland will, we hope, be diffused through all our people, all sharing in the growing prosperity.”

The distribution of wealth in our country is as pertinent today as it was one hundred years ago.

And Collins used an economic argument to promote the idea of unity on the island: “A prosperous Ireland will mean a united Ireland. With flourishing trade, our North-East countrymen will need no persuasion to come in and share in the healthy economic life of the country.’

But Collins always understood that, no matter what the issue, he would have to sell it to the people of Ireland, bring them with him, and in effect empower them by doing so.

It was in this regard that, returning to the essence of our Gaelic civilisation, he combined the visionary statesman with the arch pragmatist when he wrote: “We have to build up a new civilization on the foundations of the old. And it is not the leaders of the Irish people you must look to, but yourselves.

“Leaders are but individuals, and are imperfect, liable to error and weakness. They can but do their best to establish a context which will enable you to do it for yourselves.

“The strength of the nation will be the strength of the spirit of the whole people.’

When Michael Collins died, on August 22, 1922, he was 31 years of age.

App?

App?