Like Clare in 1995, Cork's confidence is being eroded every year they don't lift the All-Ireland

Cork's loss to Tipp, and the manner of it, was a crushing blow to the county's confidence. Picture: INPHO/Ryan Byrne

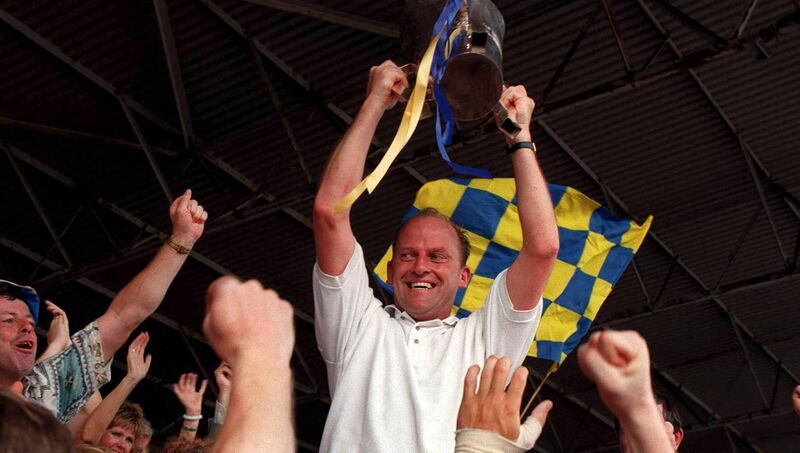

Thirty years on from Clare’s historic All-Ireland final breakthrough in 1995, Eoin Sheahan from Newstalk’s

sat down with Ger Loughnane for a wide-ranging 75-minute interview which was aired on the show on Tuesday evening.

That journey has been documented at length, but any time Loughnane speaks about that time he has always neatly encapsulated how a group of unyielding personalities transformed an eternity of disappointment into a glorious era of success for a county that had never expected to reach those heights.

Before Loughnane took over in the autumn of 1994, the ambitions of Clare teams existed in a state of anxiety, often being tranquilised by a fear and trepidation that almost always turned into a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Clare didn’t win big games, especially Munster finals. Clare had been hammered in successive Munster finals in 1993 and 1994 by Tipperary and Limerick, both of which reaffirmed the oppression Clare had always felt and could never seem to escape from.

Loughnane had a clear vision of what he wanted to do and how he intended to go about doing it; speeding up Clare’s hurling; getting the team fitter and stronger than any other hurling team had been before; and finding enough players with the right character to complete the puzzle.

That Clare team was loaded with leaders, but Loughnane realised after the 1994 Munster final loss to Limerick that some of the players were not mentally strong enough. So he replaced them with a raft of young players from the team which lost the 1994 Munster U21 final to Waterford.

That U21 team was completely underrated and under-valued but six of that side – Seánie McMahon, Ollie Baker, Frank Lohan, Stephen McNamara, Fergal Hegarty and Eamonn Taaffe - played in the All-Ireland senior final 14 months after losing that U21 final.

Four of those six players were U21 again in 1995. Only McMahon had been on the senior panel the previous year but Loughnane identified young players with the required character and mental toughness that ultimately made the difference to that Clare team. Only five of the starting 15 from the 1993 Munster final started the 1995 Munster final.

Cork aren’t exactly in a similar position now to where Clare were in 1994, especially when Cork have always had a history and a heritage of success that Clare never had prior to 1995.

Yet that old confidence is being eroded with each passing year that Cork don’t win an All-Ireland.

Loughnane was an inspirational leader and communicator but one of his greatest strengths was how he changed the perception of that team from serial losers to stone-cold assassins. That will be one of Ben O’Connor’s greatest challenges now to try and alter that perception of Cork as a team who cannot get over the line.

That might sound harsh on a side that has sacked Limerick in the championship three times in 13 months, but this group will only be judged and measured by All-Ireland success.

Similar to Loughnane, O’Connor will have to go down a different road, not just to put his own stamp on the group, but because Cork need to move forward with new players, or players who haven’t the same mental baggage with trying to get over that line.

Cork were extremely unlucky in the 2024 final but the reality is that a lot of the current group have lost two All-Ireland finals in five years by a combined margin of 31 points.

Cork can argue about the context of the Limerick round robin game back in May, and that they didn’t need to win, but any team with serious All-Ireland ambitions should not lose a championship match by 16 points.

Cork did return to beat Limerick in the Munster final but that Limerick team in their prime never shipped a defeat that big.

Limerick’s heaviest defeat was a five-point loss to Clare this year in a dead-rubber round robin match.

Cork have done so much right in the last few years but the cracks that appeared in the Gaelic Grounds in May reappeared in the All-Ireland final. Similar to Loughnane, O’Connor needs to pack his side with players who refuse to accept defeat, people who will never give up, guys who will do whatever it takes to get over the line.

Doing that will also change the perception that often clings to elite sports teams who can’t get to where they need to go.

“If you’ve got a wound, people will always find easy ways to stick their finger in that wound,” said then Spurs manager Ange Postecoglou after his side squandered a two-goal half-time lead to lose 3-2 to Brighton last year.

“If we want to change the perception of ourselves, it will only come if we're proving we're a team that can be relentless in our approach and be successful."

Thomas Frank is tasked with that challenge now, but Spurs have repeatedly failed to alter that view of themselves as a club. Loughnane’s Clare though, did.

“Character is the one thing that endures,” said Loughnane on Newstalk on Tuesday. “It’s not the excitement that endures, it’s the satisfaction that there is a (perceived) massive obstacle there that will never be overcome.

"That group overcame it. And there is a lifetime of fulfilment in doing that.“

Just moments after the 1995 All-Ireland final win, Tony O’Donoghue collared Loughnane for an interview for RTÉ.

“This time last year we were in the depths of despair,” said Loughnane. “But we weren’t going to surrender.”

And that has to be Cork’s attitude now going forward.

![IMG_2036[1].JPG Junior A Hurling: Douglas hit Bishopstown for eight goals at Ballinlough](/cms_media/module_img/9541/4770941_1_teasersmall_IMG_2036_5b1_5d.jpg)

App?

App?