'It's locals who are most devastated by the decision': End of an era as St Francis Friary closes

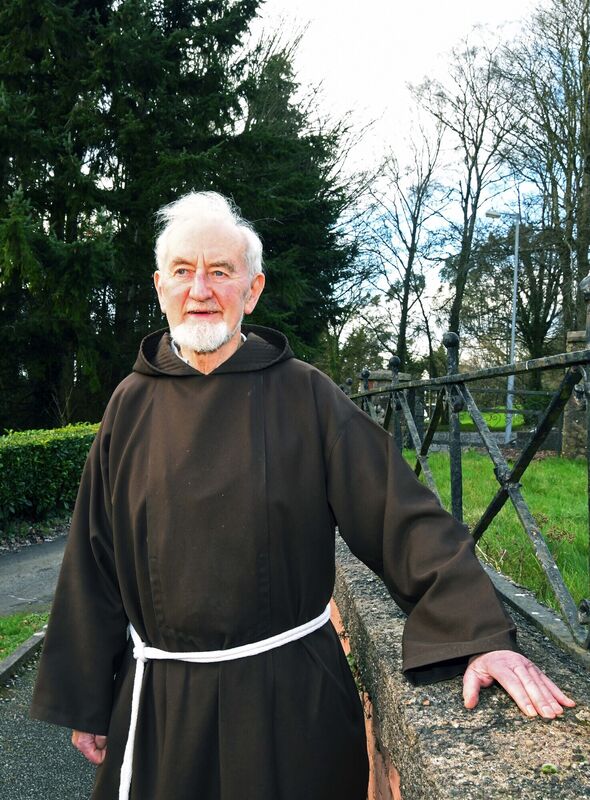

Fr. Silvester O'Flynn, OFM Cap., Guardian of Rochestown Friary, Cork, in front of the original chapel (left) and part of Rochestown College. Picture Denis Minihane.

WALKING through the grounds of St Francis Friary, Fr Silvester O’Flynn is anxious to talk about the local people of Rochestown, who he says have been worst affected by the Capuchin order’s decision to close the friary.

“We’ve been here since the 1870s, and in all that time we have been providing a social centre for the area, and it’s the locals who are most devastated by the decision to close,” Fr Silvester tells The Echo.

“I had to tell the congregation at Mass and my voice almost broke.

“We were so grateful to the local people, because they supported us from Day One, and we couldn’t have built our church here unless the local people co-operated with it.

“The main processions going to the grotto, they were huge. And, of course, wherever the Capuchins went, they opened a hall. You had the Fr Mathew Hall in Cork, similarly there were halls in Dublin and Kilkenny. What was initially called the temperance hall here, 1913 it started, then it was called the Marriott hall, and it was the centre for plays, whist drives, badminton, it was the whole centre.

“The local boys in particular, the girls to a lesser extent, were involved, it was never called a youth club, but it was in effect a youth club.

“We’re just grateful to all the people who worked on the farm, who were cooks for us, and we just want to express our gratitude to them. Hopefully before we go there will be some sort of a celebration.”

Stopping by the grotto, he says the decision to close the friary was a painful one, he says, but necessary in a time of dwindling vocations and ageing friars. He stresses that the decision will not affect the adjacent St Francis College, and the friars will continue to sit on the board of the popular secondary school, providing a “link friar” to offer sacramental and pastoral assistance to the school community.

A young-looking 80, he talks passionately to The Echo’s reporter and photographer about the history of the friary, and he explains its origins in the greater context of its times.

“Before you had the Rising, Irish people began to rediscover their identity from the 1850s and 1860s, and, gradually, we rediscovered the language that had been driven out of the schools,” he says.

“The oldest Feis is not the Feis Ceoil, but the Feis Maitiú, in Douglas,” he says, pointing to a stone in the friary’s graveyard.

“And there’s the man who founded the Feis Maitiú, Fr Micheál O’Shea.”

Fr Silvester went to school here in the 1950s with two of Fr Micheál’s nephews.

He points to another gravestone: “Columbus Murphy, a quiet little man, he was based in Church St in Dublin, and on the Thursday of Easter week, shooting started on the Monday, and on the Thursday Padraig Pearse decided enough devastation had been done, and he wrote a letter of surrender and gave it to his friend, Nurse O’Farrell.

“How would she get it across the Liffey, over to General Maxwell? Nurse O’Farrell was coming up Middle Abbey St and Father Columbus came out of the Jervis Street Hospital, he’d just said Mass over there, and she grabbed him and said: ‘This is the letter of surrender, and neither side will shoot you, so bring it over to General Maxwell, over to Dublin Castle’, which he did.”

Warming to his story, Fr Silvester adds that Fr Columbus then had to get the message to surrender out to Dublin’s southside, to Thomas McDonagh and Éamon de Valera and others in Boland’s Mills and the Dublin Union.

“They had loads of ammunition left, and they didn’t want to surrender, they wanted to hold on for another few days — ‘We’ll get more propaganda around Europe and everything and we’ll be getting the people on our side’, which they weren’t, actually. The people wanted the whole thing to stop.

“Columbus went back to Church St and he got Father Augustine, who is buried back there. Augustine was an eloquent man, where Columbus was a quiet man. Augustine was great friends with the Pearse family, so they’d be far more likely to listen to him. So Augustine argued it out with them, and they agreed. Now, they surrendered and they were arrested there and then, and were taken off to jail.”

He draws our attention to a memorial plaque to two priests.

“Now, we have Dominic and Albert. The two of them in the Civil War ministered to both sides, the Irregulars as well as the Free Staters, which didn’t go down very well with the bishops,” he says.

“And then the Civil War ceased, they were advised to get these two men out of the country. We had opened a mission in California and the two of them were sent out there. Both of them died relatively young. Dominic was only 52 and Albert was 48.”

Initially buried in the United States, they were repatriated in 1958, the year Fr Silvester did his Leaving Certificate.

“Dominic was an interesting character. Dominic had been a chaplain with the British Forces in the First World War, he had a two-year contract from 1915 to 1917. When he came back then he got involved with the IRA, and he was chaplain to the Cork Brigade. He was chaplain to the lord mayor, chaplain for Tomás Mac Curtain, and for Terence MacSwiney, and he spent 84 days in Brixton prison, visiting MacSwiney every day.”

When Fr Silvester was based at Holy Trinity, Dominic’s brother would come to Mass every morning, and he presented Silvester with Dominic’s Mass kit from his chaplaincy days. It now rests safely in the Capuchin archives in Dublin.

“From my earliest days I always wanted to be a priest,” Fr Silvester says with a smile.

“I had three uncles priests on my mother’s side, and she had a sister a nun. From my father’s side, he didn’t have any brothers, but he had several cousins who were priests. We were rotten with religion!

“It was the family business. I have a sister who’s a nun.”

A Ringaskiddy native, he attended St Francis College as a boarder, and found himself drawn to the Capuchins’ way of life, joining the order after his Leaving Cert, alongside five other past pupils. There have been no vocations from St Francis College since the late 1980s.

“Those were the days! Could we have foreseen so many years without any vocation from the college?”

St Francis College was founded in 1884 and it was a boarding school up to the 1980s. When Fr Silvester was a student in the 1950s, it had approximately 100 students. From the late 1980s on, the all-boys college had about 300 pupils, and now it has over 700 students, with plans to expand its premises to accommodate more than 900 students.

The college, and the friary before it, were founded in a different Ireland, one emerging from the dark days of the Great Famine and mass emigration, with the shadow of the Penal Laws still hanging over the land. Fr Silvester points out that Fr Mathew is not wearing a habit on St Patrick’s Street because clerical garb was not allowed.

“There was only a very small number of Capuchins in Ireland at the time, and while Maynooth and other seminaries were open, there were no seminaries allowed for the religious orders, and they had to train on the continent, so naturally enough vocations were low,” he says.

“We got help then from Belgium and Italy, and we had the friary in Dublin, and in Kilkenny and in Cork, in Holy Trinity. Fr Mathew had that friary and he also began the building of the church, but it was ages before that was finished. The Famine, of course, slowed down the whole thing.”

One Italian friar, Cherubini, purchased the Rochestown land in 1873 and soon a community formed there, building a church, which opened in 1877.

“Against the law of the land, they were the first to wear the brown habit. This was just a residue of the Penal Laws, they weren’t going to be arrested, but it was still on the legal books.”

The college was founded in 1884 — “just by coincidence the same year the GAA was formed” — to foster vocations in the Capuchin order.

Fr Silvester feels the college at the time was feeding into a new, more optimistic Ireland with an emphasis on Irish culture and music, the Ireland of Conradh na Gaeilge, the Abbey Theatre, Yeats, and Synge.

The Capuchins’ decision to close St Francis Friary in Rochestown, and St Anthony’s Friary in Carlow, as well as their withdrawal from St Francis Parish in Dublin, comes at a time when there are 65 friars in Ireland, with an average age of 76, and only 10 who are under the age of 70.

“We decided that six communities would be as many as we could cope with, three had to go, so we had a process of discernment going on over two years,” says Fr Silvester.

“We all had a say in it, even if we didn’t like the fact that our particular community was closing down. We knew that some had to go and there were various criteria that would have guided us. If there was another Capuchin presence nearby, we wouldn’t keep the two open, and we have Holy Trinity five miles away from us.”

There are about 10 friars in Holy Trinity, he says, and six in Rochestown, five residential and one of the community is full-time chaplain at St Finbarr’s Hospital.

The world has changed a lot since Fr Silvester joined the Capuchins in 1958, and he notes that while vocations are a rarity now in Ireland, there are parts of the world where they are growing.

“When we had a surplus of vocations here, they were going out to South Africa and what was then Rhodesia, to New Zealand, California and in more recent years Korea. Those are blossoming with vocations now. There are only two Capuchins left in Zambia, there was a time there were 64, and only one African Capuchin. Now it’s the other way around, you have over 60 African Capuchins now, and from July on, there’ll be only one Irish Capuchin.”

Does he think the world will turn again, and is there the potential for a revival in this part of the world?

“I firmly believe,” he says. “The image I take is the tide has to go out full before it starts to come in again, and it’s how long more does it keep going out before it starts to come in again? And the history of the Church shows that vocations have always gone up and down, and when the Holy Spirit strikes and someone comes in with an idea that has reached its time. It happened in the time of Francis, and Dominic, and it happened in the 1500s after the Protestant Reformation.

“If you go back to Pentecost, the apostles were locked up, then Jesus was gone from them, they didn’t know what to do, what to say, they had minimal training, and the Holy Spirit came within a week.”

Despite the closure of St Francis Friary, Fr Silvester is optimistic for the future, and he believes Pope Francis has the right approach to the future of the Catholic Church.

“Let’s get walking, and talking, and listening together. Where is the Holy Spirit leading us?

“When you see that bigger picture of things, the tide starts coming in and at the time of the full moon, when the tide goes out furthest, that’s when it comes back in more rapidly than ever before,” he says.

“I’m full of hope.”

App?

App?