Books: How legacy of Big Fellow has changed down the decades

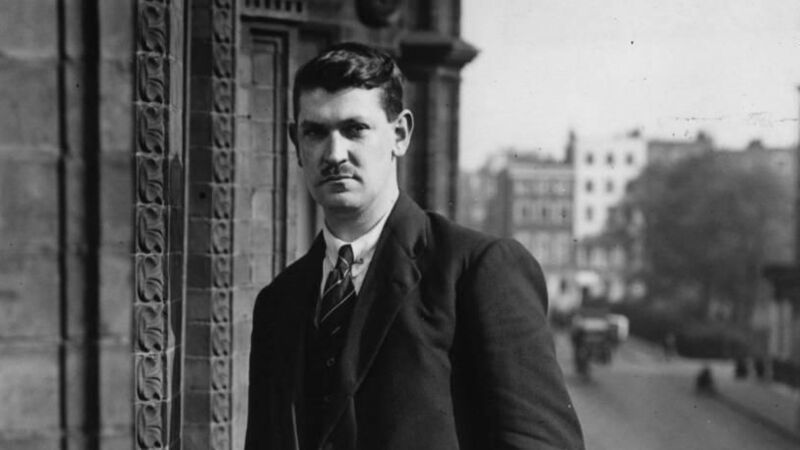

Michael Collins in October, 1921, while in London for the treaty negotiations

Michael Collins has been the subject of more biography, commemoration, politicisation, and artistic expression than any other character in modern Irish history.

So why another book?

The study of history never stands still.

New methodology, new source material, and alternative interpretation will continue to alter our understanding. There will be new biographies of Collins. But this is not one of them.

This book concentrates on what happened after Collins died, and how his memory was used, and sometimes abused, in the construction of the historiography and mythology which informed of the man and propagated the legend.

From the moment he died 103 years ago today, on August 22, 1922, Collins became both the memory of a man and a symbol of political ideology.

Because his own political thought process could no longer evolve, his symbolism could be used to advance any political viewpoint.

In Michael Collins House Museum in Clonakilty, near his birth place, people frequently tell us what Collins ‘would have’ thought about everything, from immigration to vaccination.

Politicians have informed the public (often with a straight face) about his views on issues such as housing and Ireland’s membership of the European Union.

The symbolic Collins is all things to all men.

In the immediate aftermath of his death, Collins was the ultimate symbol of stability sought by the Free State Government of the time. His enormous funeral was both a very genuine outpouring of a nation’s grief, and a political spectacle for a government almost literally under siege.

It was followed up by the rushed commissioning of a huge temporary cenotaph dedicated to both Collins and Arthur Griffith - who had died ten days before Collins - on the lawn of Leinster House.

Kevin O’Higgins was added later to complete the Free State’s holy trinity.

For a few years, the cenotaph was the focal point of a huge military parade held every August.

But, by the late 1920s it was showing its age and the Government was warned that it might fall.

By then, some of Collins’ closest comrades had fallen out with WT Cosgrave’s Government and had almost expressed their outrage at the downsizing of the Army, in mutiny.

Cast into the political wilderness, those men commemorated Collins at his grave in Glasnevin every year.

They were a visible reminder that the Free State’s new elite did not have the approval of all of Collins’ comrades and that was the likely reason that Cumann na nGaedheal failed to mark Collins’ grave despite his brother’s requests.

The stone originally intended for that purpose was ultimately erected in Béal na Bláth in 1924.

By the time that Collins’ Free State comrades departed government in 1932, their actions and inactions had ensured that Éamon de Valera inherited a crumbling cenotaph and an unmarked grave.

Faced with the choice of tearing the cenotaph down to facilitate its replacement, or letting it fall, de Valera knew that either action would result in his being accused of disrespecting Collins.

He opted for the former course and co-operated with his Fine Gael opposition to design a new cenotaph.

It was eventually completed after World War II and stands on Leinster Lawn to this day - though most people probably don’t even know it’s there.

de Valera also did what Cosgrave had never done and made provision for Collins’ grave to be marked.

Later, a misunderstanding regarding the legal process surrounding that marking, ensured that he was accused of petty vindictiveness in ascribing measurements to the headstone. It was the story of his post-Collins political life.

No matter how many Collins masses de Valera attended, he could never attend enough. Whatever he said, he shouldn’t have said, and what he didn’t say should have been said.

Even his oft quoted ‘opinion that in the fullness of time history will record the greatness of Michael Collins and it will be recorded at my expense,’ may never have been uttered.

If he did say it, it was used as a diplomatic refusal to patronise a Collins memorial body which was then openly involved in an internal Fine Gael dispute.

It was all part of a well-worn narrative where Fianna Fáil (often petulantly) ignored Collins, and Fine Gael (often erroneously) accused them of calculated disrespect.

Fine Gael governments sent the Army to Béal na Bláth to honour the Commander in Chief, Fianna Fáil argued that the office pre-dated the Civil War and didn’t send the Army to any Civil War commemoration of either side.

Each accused the other of failing to heal the wounds of the past.

Cork Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Jack Lynch eventually relented and sent the Army in 1972. Shortly afterwards, Liam Cosgrave decided that the Army’s presence was no longer necessary.

By then, the Béal na Bláth commemorations had lost their Civil war edge and their orations frequently focused on criticism of the violence then being perpetrated by the Provisional IRA in Northern Ireland.

The Northern conflict overshadowed the evolution of Collins’ symbolism too.

Although he had featured in Hollywood films under different guises, he was on his way to his eponymous silver screen debut before violence broke out in 1969.

That ensured that Neil Jordan would have the honour of debuting Collins almost as soon as that violence subsided almost 30 years later.

With Jordan’s film came a boost in books sales, tourism products, and even whiskeys and beers donning Collins name.

From political symbol to icon of commemorative fervour, and from historical study to tourism product, this book builds on the work of others like Ann Dolan and William Murphy in examining what they called the ‘after-life’ of Michael Collins.

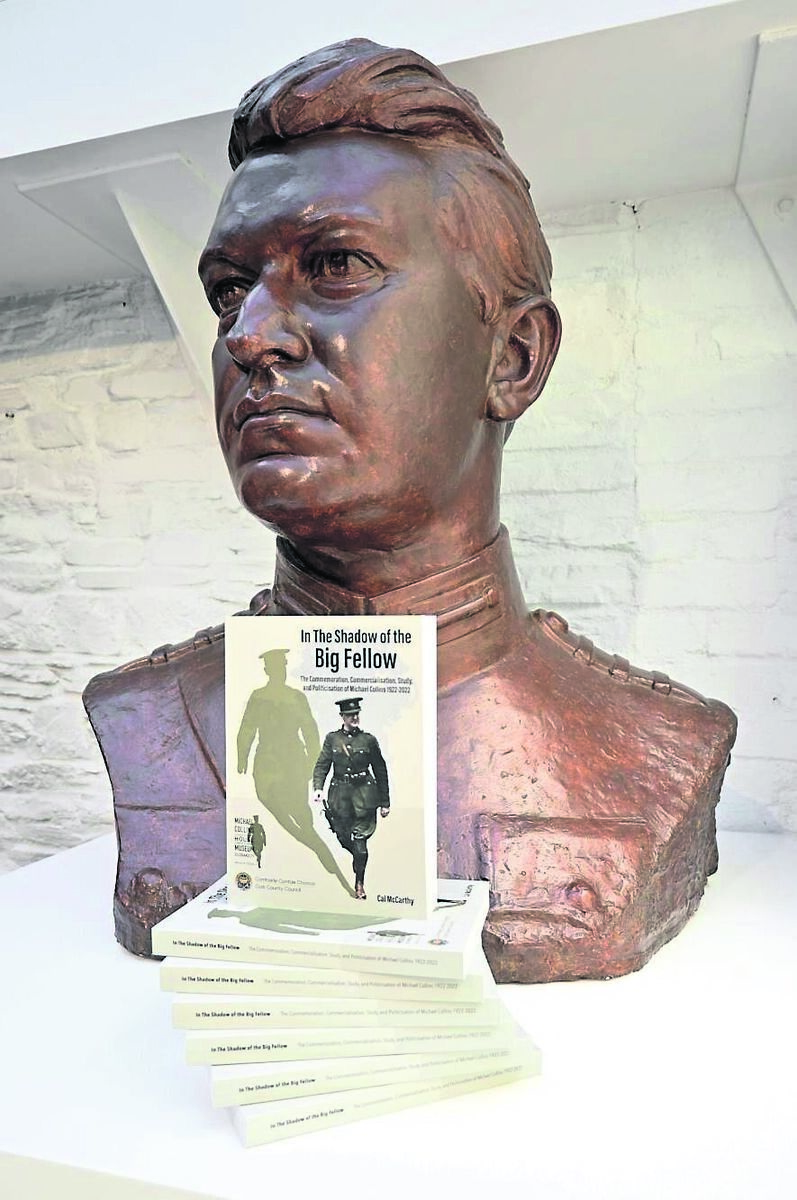

In The Shadow Of The Big Fellow is the first major publication from Michael Collins House Museum and builds on the Cork County Council museum’s content to help grow public understanding of Ireland’s revolutionary past in an accessible manner.

The publication, made possible with the support of the Cork County Council Commemoration Committee, provides an intriguing read for both enthusiasts and academics, as well as the more casual reader.

App?

App?