Cork city factory had its own fire brigade

The Harrington and Goodlass Wall Works Fire Brigade in 1954. Back: Martin Power, John Daly, Danny Sheehan. Front: Gerald Foley, Christy Power, Redmond Burke, Peter Crowley, and Gerry Healy.

Nervously, and with ever-deepening trepidation, I climbed the stairs to the first-floor offices on that long-ago May morning of 1962.

It was a Monday, and I was starting my first real ‘summer job’ with Harrington and Goodlass Wall on Commons Road in Cork city - school beckoned again in September.

As nonchalantly as my (almost depleted) reserves of courage would allow, I quietly whistled the hit of the day - Elvis Presley’s follow That Dream - to myself:

When your heart gets restless, time to move along

When your heart gets weary, time to sing a song

But when a dream is calling you

There’s just one thing that you can do…

I really didn’t know what to expect. I needn’t have worried. My fears soon dissipated as my genial ‘hosts’ introduced themselves - Raymond Connole, Bill Angove, and Terry Doran - and quickly put this wet-behind-the-ears teenager at ease. Gentlemen all, I couldn’t have asked for more affable mentors.

Over the coming months, I was able to observe, at close quarters, the well-trained members of the company’s Works Fire Brigade at practise - and also responding to real-live incidents - under their fire officer, the avuncular P. J. (‘Jack’) Manning.

I was not to know that, in a few short years, as a member of the city Fire Brigade, I would stand shoulder to shoulder with Jack and his colleagues as we helped fight some of the biggest - and most dangerous - conflagrations seen in Cork in years.

******

The label ‘merchant prince’ has often been bandied about in Cork, but the Harringtons really were of a different ilk. They were from what Corkonians call ‘Old Money’; the Real McCoy; the genuine article.

The three brothers who founded the paint company - William, Ignatius, and Stanley - were brought up in a mansion, Lee View House, Montenotte (now, the Montenotte Hotel). Their father, William, had a thriving pharmaceutical business and was a City Magistrate. To underscore his position in the establishment, he was married to the daughter of the Comptroller of the Inland Revenue for Ireland.

In the early 1880s, his three sons founded the firm of Harrington Brothers and acquired over two acres on Commons Road on which they built their Shandon Chemical Works (later, Harrington and Goodlass Wall/Dulux Ireland).

The works, which came on stream in 1885, were renowned as the only makers of ‘Fire Red’ rust protection paint anywhere in the UK, and their distempers and varnishes (particularly their coffin varnish) were the only Irish-made ones and much in demand.

Sidelines included potato blight spray and cattle medicine. Additionally, they were the principal suppliers of inks and colours to newspapers and the printing industry.

In the 1930s, the firm’s Research Department, in partnership with UK chemical giant ICI, developed a revolutionary non-fading pigment called Cadmium which was supplied to the spray booths of the Ford Motor Company. Later still, the best-selling Weathershield exterior masonry paint was first developed at the Cork lab.

However, like the nearby flax mills of the Cork Spinning and Weaving Company (later, Sunbeam Wolsey), the site was carefully chosen, not for any lofty philanthropic ideal of creating employment in a community where unemployment was rampant (although, it must be noted, both concerns provided good employment), but by the hard-nosed business decision to avoid paying rates to Cork Corporation, for both sites lay well outside the borough boundary.

This crafty move proved a somewhat Pyrrhic victory for it later cost both companies (in particular, the flax mills) dearly. The city’s fire hydrant network ended at the start of Commons Road, an appreciable distance away. When fire broke out (on a number of occasions) in both factories, great delay was experienced before effective firefighting water was brought to bear, leaving both firms greatly exposed.

One of the earliest recorded fires involving chemicals at a Cork factory occurred at the Shandon Chemical Works on the morning of Tuesday, November 24, 1891.

The Cork Examiner outlined what happened: “What narrowly missed being a disastrous fire broke out at Harrington’s Chemical Factory, Blackpool. A two-storey building in which was stored numerous jars of chemicals was observed to be burning. The alarm was raised, and in a few minutes the hands employed in the place turned out, and vigorous efforts were made to subdue the fire.

The City Fire Brigade was communicated with and were in attendance without loss of time. All efforts were now directed to confining the fire and in this the Brigade was successful. In the building in which the fire took place were carboys of sulphuric acid and other acids, and a large quantity of chemicals. Were it not for the promptitude with which the burning was encountered the results must have been very serious.”

Apart from the dangers created by the fire, those who moved the sulphuric acid - ‘the baskets around which were blazing’ - were putting themselves in grave peril: carboys, when heated, frequently crack. A splash on the skin has a powerful corrosive action, causing great pain and severe burns.

The fire was traced to the overheating of a flue underneath the sheet-iron floor of the chemical store.

City fire chief, Captain Hutson, prevailed on the Corporation to extend the city’s fire main beyond the borough boundary for the protection of these two important industries. His recommendation was not acted upon, and in 1894 more than 600 people found themselves out of work when the flax mills burned down and the Fire Brigade, once again, experienced major water difficulties.

******

By the 1950s, the original plant had spread far beyond the bounds of its original footprint. But with expansion came fresh methods, improved processes and new materials, many of which carried with them urgent demands for careful thought about combating the risks inherent in their use. New materials can have a high risk of combustion, a modern process can produce toxic waste, and a new method can be responsible for an increase in the number of accidents, including fires, if it is not properly controlled.

In an interview with the late Jack Manning shortly before he passed away in 2004, he explained how their brigade came to be formed:

“I joined Harrington and Goodlass Wall in 1951 but, at that stage, I wasn’t part of the fire crew. To be on the crew, you had to live within hearing distance of the factory fire alarm, so all the lads lived around locally. At the time I lived over in Pouladuff, on the southside. Before our own brigade was formed, when a fire broke out, we were totally dependent on the City Fire Brigade, who were based in Sullivan’s Quay just off the city centre - about six kilometres away.

“So, after a few ‘close calls’ with fires, the factory bosses decided we should have our own Works Brigade, so they organised a fire team and acquired foam-making equipment. Even so, the first rule still was ‘Call the Fire Brigade’. That was the first thing we always did, and they’re still doing it to this day.

“Our industry comprises solvents, varnishes, and paints so we trained essentially for our hazards - all highly volatile - the most volatile of all were the solvents. My first experience of a fire was in the Varnish Plant, then situated in a corrugated hut. In the varnish making, the resin was cooked on open fires, with a man standing, stirring, all the time. At the time the Varnish ‘went up’, we still weren’t very conversant with the foam-making operation, which consisted of a man wearing a metal ‘knapsack’ on his back containing foam compound, which was then projected out through a large nozzle on to the fire. This early foam was protein-based, essentially made from horses’ hooves and ox-blood, and it smelled to high heaven. Anyway, Danny Sheehan was the man assigned to wear the knapsack, and they had used up the first lot of foam and, when refilling the knapsack, in all the excitement they forgot to open the lid, and it went all down poor Danny’s back! It must have taken countless showers, and gallons of ‘Old Spice’, to get rid of the awful stench! Howsoever, by the time the City Brigade arrived, we had the fire out and the plant was back in production by Monday. Our fire crew had come through their first major test with flying colours.”

Around this time, Redmond B. Burke was appointed Engineering Projects Manager, and preparations began for the extension of the factory. The River Bride was diverted, and waste land reclaimed, to make the most use of the ground adjoining the existing plant.

The new scheme increased the factory site to some 29 acres and the total floor area of buildings to two and a half acres. The main features of the extensions included a synthetic resin plant, a tank farm, a varnish tank and storage area, a new engineering workshop, a new fire station, and a solvent and blending station.

The revamped plant was officially opened by An Taoiseach, Seán Lemass TD, on April 18, 1963, when he inspected a Guard of Honour drawn from the brigade under Fire Officer Jack Manning.

******

The activities of the brigade were not confined to the four walls of the factory on Commons Road. In fact, when the City Fire Brigade was a much smaller entity than it is now, they were often glad to avail of the assistance offered by the HGW volunteers. The first time the Works Brigade were called into action in the city was on the night of December 12, 1955, when the old Opera House on Lavitt’s Quay was burned down, as Jack recalled; “I was on the quay when I saw this car and a fellow with a helmet on shouting, ‘Get out of the way! It was Christy Power, a HGW team member, trying to beat his way through the crowd on Lavitt’s Quay, and there was the trailer pump tied on with a rope to the back bumper of a works car. We made down the pump to the river - where Christy Ring Bridge is now - and, the tide being in full, we were able to lift the water with two lengths of suction hose. I suppose it was a good public relations exercise, but the water jets were hardly reaching the fire with the ferocity of the wind blowing that night.”

The ‘trailer pump’ in question had been purchased second-hand from Britain, 15 years before the Opera House fire, it had been fighting the enormous fires caused by the Luftwaffe Blitz on London.

The fire team’s next ‘outside duty’ was on the morning of June 28, 1963, when they were invited to provide back-up to the Fire Brigade for President John F. Kennedy’s landing by helicopter on the square at Collins Barracks.

Jack - an accomplished amateur photographer - recalled his greatest regret was leaving his camera at home that morning. “I was being too good,” he told me, “I could have driven our fire tender around the Square and taken close-up photographs of JFK and, I’m sure, nobody would have said a word to me.”

By the 1960s, Harrington’s brigade would have put many municipal townships in Ireland to shame. It included a specially-built fire station, two fire tenders (a Land Rover and a Ford V8) and a large trailer pump. (The V8 was actually an old taxi which was stripped down in their engineering workshops and converted into a foam tender, complete with front-mounted pump). The brigade was organised in two ‘Watches’ - Red and White - with about 14 members.

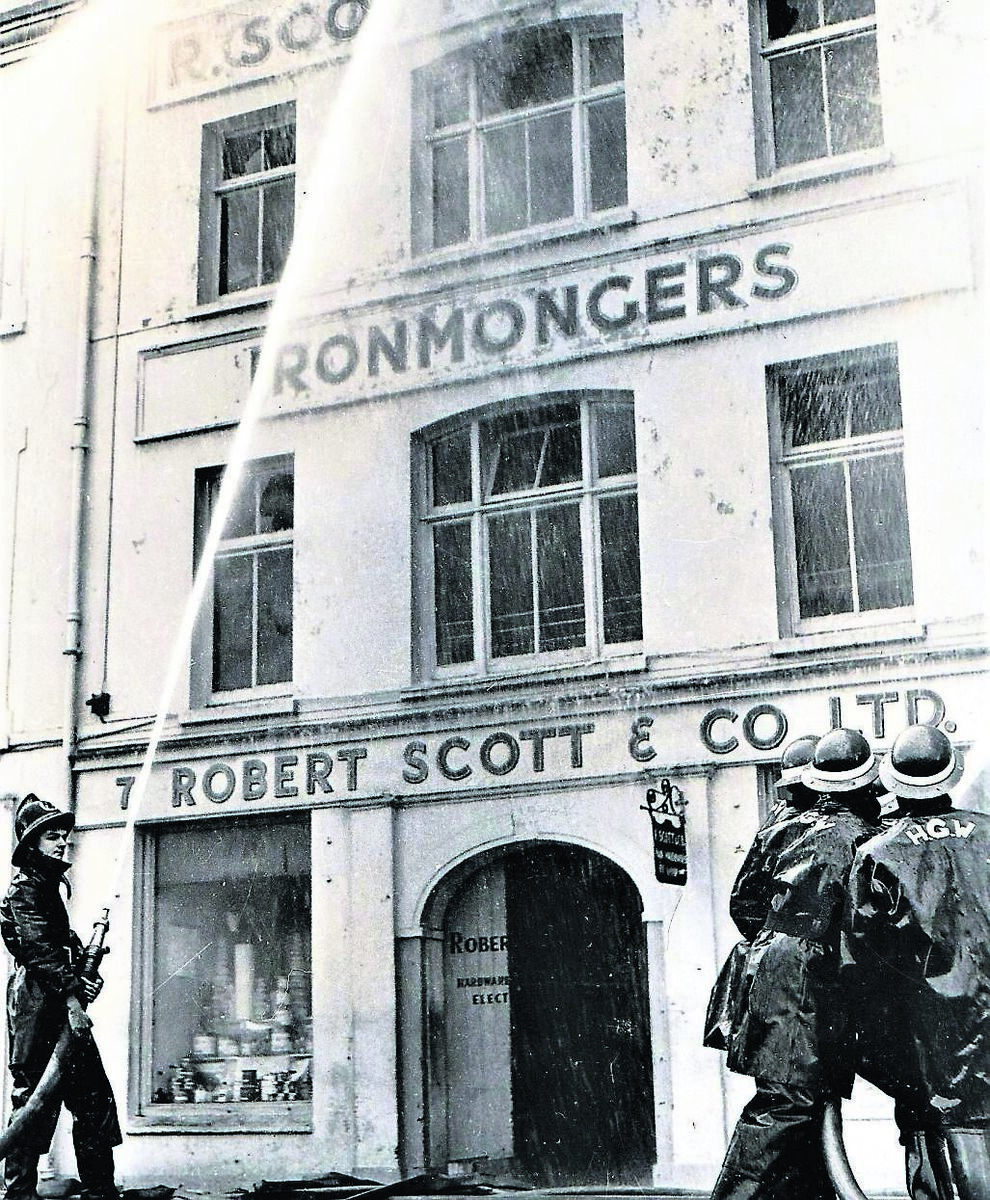

Two of the largest conflagrations in Cork city in the mid-20th century involved Suttons’ Hardware, Coal, and Seed Merchants, at No.1 South Mall, and Scott’s Hardware, a large complex that stretched from MacCurtain Street back to St Patrick’s Quay. Both premises were burned down in spectacular day-time blazes on November 29, 1963, and February 13, 1965, respectively.

In the county, fire quickly raced through the polish manufacturers of Punch and Co, Glanmire, on the morning of July 30, 1964, leaving the multi-storey factory a blazing inferno.

In all instances, the offers of help from HGW were gratefully accepted by the fire authorities. (As one who was present at all three fires, I can confirm their appearance on the fireground was always received with a sense of relief by the hard-pressed firefighters. The word would go round, ‘Harrington’s are here!’).

Jack recalled that one of the highlights of his time with Harrington’s was being instrumental in organising a firefighting competition among industrial concerns: “I was over in Stowe, Vermont, and visited a factory very much like our own, and I saw this beautiful trophy on the wall of their fire station, and it turned out to be for an industrial fire competition. Tell me about it, I said, so the Safety Officer gave me the Drill Book and all the ‘goings-on strips’.

“When I got home, I studied them and the result was the first Industrial Firefighting Competition in Cork since the days of the Emergency, held in 1974. Metal Products, Goulding’s, Verolme, Gulf Oil, to name but a few, entered teams, and it just took off from there.”

Ironically, the biggest blaze to receive the attention of the HGW brigade occurred a stone’s throw away from their own premises. At around 2pm on September 25, 2003, the nearby Sunbeam plant caught fire and by 2.30pm was fully involved.

The main building comprised the five-storey brick and stone textile factory (the old ‘flax mills’ of earlier fires) which housed Refond Textiles Group, where once generations of Cork families were employed.

In terms of area, it constituted the biggest blaze in the city since the ‘Burning of Cork’ in December 1920.

David Hughes, Operations Director, Dulux Ireland, summarised the brigade’s role in the history of the company when he remarked, proudly: “They were the first line of defence.”

The writer is indebted to the late Mr Jack Manning for his insights into the origins and development of the Harrington and Goodlass Wall Works Fire Brigade.

App?

App?