Cork author pens a book about sport... and life, and death, and more

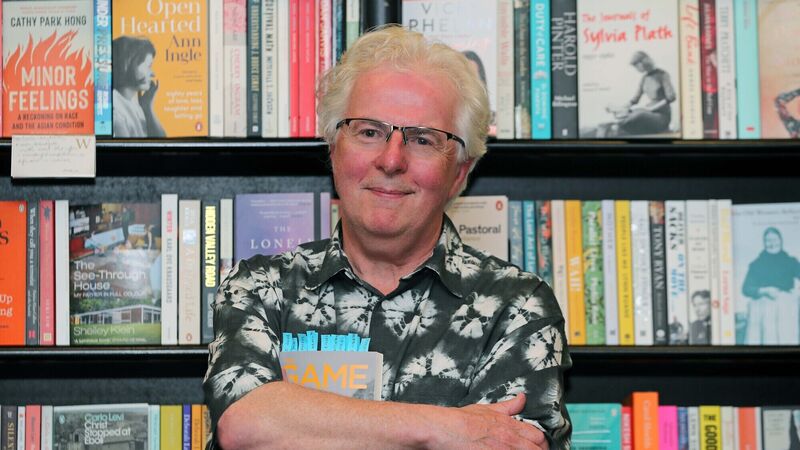

Tadhg Coakley, Author, who has launched The Game: A Journey Into the Heart of Sport. Picture: Jim Coughlan.

TADHG Coakley’s latest book is about sport; the role it plays in our lives and the deep devotion it inspires in so many people.

But like all the best writing, in The Game: A Journey Into The Heart of Sport, Coakley is writing about much more than sport, about family and memory, and about belonging and what it is to be alive.

He tells The Echo he was inspired by the current resurgence in the essay format, both here and abroad, and advised and supported by fellow writers, including Sally Rooney.

The Game is Coakley’s fourth book and he describes it as in some ways a step on from his debut, The First Sunday In September. That novel in stories told the story of a fictional All-Ireland final Sunday, from the points of view of several recurring characters

“I realised when I had written it that I had been hiding behind the characters in the book really, giving my take on sport through them and in their voices,” Coakley says.

“And I decided that I have to be brave here and write about my own experiences in sport. I thought the essay form might be a good one.”

Coakley shared his goal with Rooney, who was editor of The Stinging Fly at the time.

“She gave me some great advice, she said the essay has to be both subjective and objective,” he says. “So you have to write about yourself, otherwise it is a kind of academic exercise, but at the same time you have to have a point.

“She said, think about what you want to say about sport and tell that through your experiences.”

Coakley started writing and the following year sent two essays to fellow Cork writer Danny Denton, who had by then taken over as editor of The Stinging Fly.

“He published one of them and that really got me going on the process then.”

Coakley name-checks many writers, both Irish and from abroad, whose essays prompted him to try this format, including Emilie Pine, Sinéad Gleeson and Patrick Freyne.

“I’m a novelist by trade and my inclination is to make up characters,” he says. “But I had been thinking about sport for a long time and felt I had enough to say.

“I was inspired by those people - Zadie Smith, Olivia Laing, Amy Liptrot - who in some cases were writing about much tougher subjects, like grief and addiction and so on. I think the essay does something. Fiction does amazing things too, and I write about fiction in the book as well and art generally. But there is something in the essay form.”

The structure allowed Coakley address less frequently-tackled aspects of sport in The Game.

“Most sports books are about elite players - they play for Ireland, or they have multiple All-Ireland medals for their counties,” he says.

“I’m not that, I didn’t play at the elite level. I felt that we haven’t really explored enough, why is sport so important to us, and I tried to do that.”

So where does that love of sport come from?

“I think it is because we feel so much emotion through sport,” Coakley suggests. “We want to feel - it means we are alive if we are feeling this emotion. It starts in play and we learn to play as babies, so when a mother plays peek-a-boo with her baby, the baby knows it is play and enjoys it. Then, when we get a little bit older the games get more sophisticated. So a toddler being chased by her father who is pretending to be a monster, for example. The toddler loves this, they feel the excitement. Then, when we go to school, we learn about organised sport. We learn how much it means to our parents and older siblings and friends, we want to be part of that.”

With that knowledge comes deep emotional connection.

“Men are not good at expressing their emotion but we can really do it through sport,” Coakley says.

“We feel so much, especially at the moment of big games, we have this emotional release. We get it through music and art and books as well. But sport is by far the most popular way, for men especially.”

Coakley examines the connection between sport and childhood emotion in The Game, seeing it as the key driver of people’s connection with sport. He highlights two essays in particular. “One is about my mother and one is about my father,” he says. “When I was 18, it is my only memory of my father kissing me. I was in a Cork team and we won the All-Ireland and when I came back to the train station in Cork, my father burst through the crowd and he kissed me. That’s one of my favourite memories of my father. It all goes back to childhood.

“Let’s say Mayo win the Sam Maguire Cup. Everybody (in Mayo) my age, whenever it happens, they will burst into tears. They won’t be in control of their emotions.

“And the reason I think they will burst into tears is they will be remembering the people they lost and all the grief in their lives and that will all come out in that moment. And we want that, it means we are alive. It is very precious to feel these kind of emotions.

“Children don’t cry when they win, adults cry when they win and children cry when they lose. And that is because children have never known grief and loss.”

While his passion for sport shines through each page, Coakley believes it it also important to acknowledge the negative aspects of sport, particularly at the elite level.

He points to plans for a new breakaway Saudi-backed golf series and the venues selected for soccer World Cups as examples.

“We can’t ignore these things, the sports- washing that goes on by countries like Qatar and Russia, who had the last soccer World Cup,” he says.

“I’m really sorry now that I watched that World Cup, given what Russia are doing now, and they used that World Cup to boost themselves in the world and to increase nationalism.

“So I won’t be watching the World Cup in Qatar this year because they have a terrible human rights record, they spent €200 billion developing the infrastructure but 4,000 workers have died in the building of those stadiums and I can’t see the justification to ignore that.”

Would he like to see more people make the same choice?

“I would, I think it’s important. I know journalists have to cover the news, but as a fan, I don’t have to watch it and other people don’t have to watch it. I would like to see more of that. We have a responsibility, those of us in sport, to call it out, to make sport better.”

He believes we also need to acknowledge the negative emotions sport can inspire.

“We have to be conscious in how we consume sport as well and we have to be conscious in our emotions,” he says.

“The emotions I spoke about in my father for example, that can go into anger very quickly. We have children’s games every weekend where you hear men shouting abuse at the referee, shouting abuse at opposition, sometimes shouting abuse at their own children. We have to moderate our emotions.”

Coakley’s unflinching honesty in addressing the issues do not diminish his love for sport.

“Sport is fun, it is a great distraction from all the bad news that is there,” he says.

“I would like to see more emphasis on the social benefits and the volunteering. The benefits that adults get from volunteering in sport, for mental health, the social contract, all those kinds of things, it is huge.

“In any sport really, clubs don’t function without volunteers at the grassroots level, 99.9% of people are not involved in professional sport, but they still love it.”

For Coakley, that love and the benefits of involvement are proof of sport’s importance.

“I ask the question in the book, should we walk away from sport altogether? And I don’t think we should, because out children will lose out, we would lose out a lot ourselves.”

The Game: A Journey Into The Heart of Sport by Tadhg Coakley, published by Merrion Press. Available now.

App?

App?